Reaction to Damien Hirst’s use/misuse of Ife art image.

The insensitivity of many Westerners in the question of looted artifacts or artifacts acquired under dubious circumstances is astonishing. Hirst and other Western artists can derive inspiration from the looted artifacts kept in Western museums, which they can visit anytime they want. But where can African artists derive such inspiration when iconic African objects are all kept away in Western capitals they can’t visit?

“For, not content with being a racial slanderer, one who did not hesitate to denigrate, in such uncompromisingly nihilistic terms, the ancestral fount of the black races – a belief which this ethnologist himself observed – Frobenius was also a notorious plunderer, one of a long line of European archaeological raiders. The museums of Europe testify to this insatiable lust of Europe, the frustrations of the Ministries of Culture of the Third World and of organizations like UNESCO are a continuing testimony to the tenacity, even recidivist nature of your routine receiver of stolen goods.” – Wole Soyinka – Nobel Lecture.

There have been some very strong reactions, mainly on the part of Nigerians and other Africans, on the use/misuse, appropriation/misappropriation by the English artist, Damien Hirst, of the image of the famous Nigerian sculpture, the bronze head from Ife, Olokun, in his current exhibition at Venice, entitled Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable.

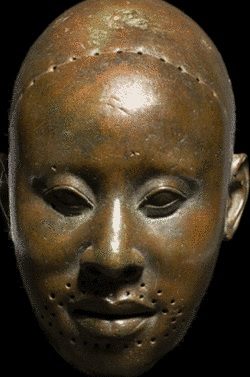

On the left is the cast brass head, Ori Olokun, an Ife head, in British Museum and on the right the sculpture by Damien Hirst, which he calls Golden Heads (Female).

Many have accused the English artist of copying Nigerian art; some said he had stolen Nigerian culture, and others accused him of plagiarizing Yoruba art. He has been called a thief, daylight robber, and many other names. Very strong reactions came from the Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor and the Nigerian painter, Laolu Senbanjo.

For the first time, Nigeria is represented at Venice Biennale by the painter Victor Ehikhamenor, sculptor Peju Alatise and performance artiste Qudus Onikeku.

We reproduce in an annex below Laolu Senbanjo’s letter addressed to Damien Hirst because it discusses many aspects of the issues involved and deserves to be read by all.

Damien Hirst is by no means the first European to have copied African art or, if you prefer, to have let himself be ‘inspired’ by African art. The great Pablo Picasso is a well-known example of Western artists benefitting from such inspiration as well as a whole lot of modern artists, the so-called avant-garde, Fernand Leger, Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Max Ernst, Constantin Brancusi, Amedeo Modigliani, Miro, Armand, etc. This ‘inspiration’ has been well discussed in several exhibitions and in the well-known book by William Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Art (1984).

Most people accept that African art was an important factor in the birth of modern art. The influence of African culture on Western culture whether in art or in music and dance as well as in other areas is no longer questioned. What is sometimes irritating is the tendency by some to minimize or to deny the role of African art. Some of the very artists who obviously have been influenced by African art even try to deny knowledge of this art or its presence in their work. Brancusi who was obviously influenced by African art tended to deny this influence. We have the statement from Joseph Epstein: ‘Brancusi, some of whose early work was influenced by African art, now declares categorically that one must not be influenced by African art, and he even went so far as to destroy work of his that he thought had African influence in it.’

Even Picasso has been credited with saying he does not know Negro art even though this has often been interpreted as a joke by the artist. But so, widespread is this tendency of denial or minimizing that even the Musée du quai Branly thought it useful to organize recently an exhibition entitled Picasso Primitif showing the undoubted influence of African art on the great artist.

A most important factor in understanding the strong reaction of Africans to the use of the Olokun image by Damien Hirst is contained in the statement by Victor Ehikhamenor:

“The British are back for more from 1897 to 2017. The Oni of Ife must hear this. Golden Heads (Female) by Damien Hirst currently part of his Venice show Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable at Palazzo Grassi. For the thousands of viewers seeing this for the first time, they won’t think Ife, they won’t think Nigeria. Their young ones will grow up to know this work as Damien Hirst’s. As time passes it will pass for a Damien Hirst regardless of his small print caption. The narrative will shift and the young Ife or Nigerian contemporary artist will someday be told by a long nose critic, ‘Your work reminds me of Damien Hirst’s Golden Head.’ We need more biographers for our forgotten.

#ifesculptures#classicnigerianart#workbynigerianartist#ifenigeria#lestweforget#nigeria#abiographyoftheforgotten”

Benin artifacts have become pan-African icons and represent excellence in African art. Corresponding to the status of the Benin artifacts, the notorious British invasion of Benin in 1897 has also come to stand for the various European imperialist attacks on African countries whether in Asante in 1874 by the British or their attack of Ethiopia in 1868 that involved large scale looting of artifacts by invading Europeans. The looting or stealing of artifacts in various European expeditions, such as the French Dakar-Djibouti Expedition (1931-1933) as well as the fascist Italian dictator Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia and stealing of artifacts, including the Obelisk at Axum in 1937, remain fresh in the minds of many Africans. The French robberies have been well documented by Michel Leiris in Afrique Fantôme.

Added to colonialist military aggressions were also the stealing by ethnologists and other European civil, military, and missionary personnel that traversed the continent under one pretext or another. The notorious German ethnologist, Leo Frobenius, whose activities in Nigeria were too much even for the British colonialists, is a good example of scholar/robber that the continent has known.

Equally annoying for many Africans is the European racist insistence on calling African art primitive/savage whilst at the same time looting and stealing our artifacts on a large scale. That designation is still being used by many scholars and dealers since it appears to correspond to their assessment of Africans and African cultures. Sometimes they put such disparaging descriptions in inverted commas and feel then authorized to say whatever else they want in their assessment.

Looted Nigerian and other African artifacts have continued to remain in Western museums and other institutions, but all calls for restitution have fallen on deaf ears. Worse, demands for restitution have been met with insulting and deprecatory arguments by Western museum directors and scholars, basically questioning the intelligence and ability of Africans. These looted artifacts are now selling for millions in Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, London, Paris and New York.

Many have also tried to present different and incomplete histories of the looted artifacts. Many Westerners have not abandoned the belief in their superiority to Africans and have even acted or spoken as if they had a God-given right and duty to preserve African artifacts even against Africans. Writings and speeches by directors of major Western museums are replete with such arrogant assumptions. They have sought to take hold and control of the narrative of African history. Whether in London or in Boston, illegal holders of looted African artifacts pretend they need our artifacts to explain African culture and history. That we Africans would also like to have our artifacts back to tell our own history seems to be a point of view that is difficult for many Westerners to understand or to accept. Some even doubt whether we are really interested in our artifacts and suppose we are only interested in getting these objects back to sell them on Western markets.

In many ways, our contemporary Westerners appear to be worse than their predecessors who stole or looted African artifacts. Old imperialists and colonialists may have acted on their beliefs in the various atrocities they committed. Our contemporary Westerners mostly reject, at least verbally, racism, colonialism, and imperialism but they are not prepared to return any of the looted objects that these evil ideologies brought to the West. Indeed, some have the impudence to reply, in response to demands for restitution, that the artifacts are better kept in the West.

When we suggest that looted African artifacts should be returned, Westerners argue that we want to rewrite history. We are not interested in rewriting history but in correcting the present imbalance whereby there are more iconic African artifacts in the West than in Africa. Indeed, nobody will contest that the best places to study African art are not Abuja, Accra, Cotonou, Harare, Johannesburg, Kumasi, Lagos, Luanda or Maputo. Those who can afford the costs involved and get a visa go to London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Boston, Brussels, Chicago, Frankfurt, Hamburg, London, Lisbon and New York. Western cities not only keep documents such as the looted historical documents of Ethiopia but also most of the archives of the colonial period. Those who want to do research in African history or culture are obliged to go to former colonial countries where the colonial archives are kept. The colonial powers looted the colonial archives and records which should have been left in the colonies at the time of independence.

We were genuinely amazed to read the text that accompanied Hirst’s Golden Heads (Female) which refers to Leo Frobenius:

“Stylistically similar to the celebrated works from the Kingdom of Ife (which prospered c.1100-1400 CE in modern Nigeria), this head may be a copy of a terracotta or brass original. Shockingly, it is only a little over a century since the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius (1873-1938) was so surprised by the discovery of the Ife heads that he deduced that the lost island of Atlantis had sunk off the Nigerian coast, enabling descendants of the Greek survivors to make the skillfully executed works.”

It is unbelievable that such a statement has been produced in 2017. It is remarkable to refer to stylistic similarity between the work of a young artist to a well-known classical work that he has ‘copied’ or that has ‘inspired’ him, creating the impression that his work had gone through a similar creative process as the established work with which he really has no connection except that it happens to be kept in a museum in his country. More explanations would seem necessary. There seems to be here a perfidious attempt and conspiracy to write Damien Hirst into the narrative of the art history of Nigeria and Africa.

Future generations would be obliged to make stylistic comparisons between the famous Olokun of Ife and the work of Damien Hirst, Golden Heads (Female). They would have to work out the similarities and differences between the Ife head and the imitation by the Englishman. Bearing in mind that Nigeria had been under British colonial domination for decades, the possible confusion of thoughts for future generations can be imagined. Some might wonder whether the style had not been imitated by the Africans to whom the British alleged they were bringing civilization, education, and culture. The presence of many Ife objects in Britain would add to the confusion. We may reach a situation such as we have in music where some seem to think African musicians have copied certain sounds from Latin American musicians. The history of Africans in Latin America is a mystery to many persons.

Could the artist and the curators not find anybody in the United Kingdom to advise them that it would be better to leave the notorious racist German anthropologist, Leo Frobenius, out of this? Had they not heard of the arrogant racist comment the German anthropologist made about the Yoruba he met in Ife? Wole Soyinka, in his 1986 Nobel Lecture, criticized Frobenius for his schizophrenic view of Yoruba art and the Yoruba. Frobenius was overwhelmed by the beauty of Ife art: “Before us stood a head of marvelous beauty, wonderfully cast in antique bronze, true to the life, encrusted with a patina of glorious dark green. This was, in very deed, the Olokun, Atlantic Africa’s Poseidon.” But the same Frobenius also expressed contempt for the people he met at Ife: “I was moved to silent melancholy at the thought that this assembly of degenerate and feeble-minded posterity should be the legitimate guardians of so much loveliness.” Soyinka has described this statement as “a direct invitation to a free-for-all race for dispossession, justified on the grounds of the keeper’s unworthiness.”

Obviously, all the political and scholarly developments since the independence of Africa states have escaped some people in the Western world, including Damien Hirst and his team. They do not seem to be aware that in discussing African art certain words must be avoided unless they express the racist opinion of the speaker himself or herself.

It is interesting that in response to the accusation that Hirst had used the Ife image without reference to its source and history, the reaction of a spokesperson for the artist is reported as follows:

“However, a spokesperson for the exhibition curator, Elena Geuna, assured CNN that there is indeed text accompanying the artwork, as well as in the exhibition guide, that makes reference to the Ife heads’ origin and concept. “One of the sources of inspiration for the exhibition is the collection of the British Museum, in London, where the Ife heads are displayed,” she elaborated. ‘An Ife head from the British Museum collection has also been included in the famous book, ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’ by the former museum director Neil MacGregor.”

The reference to the British Museum may have been given in all innocence, not being aware of the relations of that museum to looted African artifacts. Many Africans regard the venerable museum as a den for looted artifacts. The reference to a book by a former director of the museum reinforces the damage already done. The former director of the British Museum has been behind many of the feeble theories developed to defend the interests of the so-called universal museums including the notorious Declaration on the Value and Importance of Universal Museums. [6] Since Hirst’s text refers to Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects, he could have paid more attention to this statement about the German anthropologist: “It’s easy to mock Frobenius, but at the beginning of the twentieth century Europeans had very limited knowledge of the traditions of African art.”

In our time, there is no excuse for ignorance about African art nor can we accept the repetition of views that have been proved to be patently wrong. Obviously, in his efforts at myth-building, the artist liked the idea of ‘a lost island of Atlantis’ and ‘descendants of the Greek survivors’ who allegedly made those works. Myth-building at the cost of secure knowledge is no contribution to respect for a culture that one is imitating.

Damien Hirst should delete completely the entry in the catalog concerning his imitation and replace it with a statement indicating that the artist has been inspired by the Ife head in the British Museum. There should be no reference to Frobenius nor any stylistic comparison. Moreover, the postcard of the Golden Head should also contain such a statement or be withdrawn from sale. The suggestion that the object Hirst was imitating might itself be an imitation is not very clever. But this artist seems to thrive on provocation and controversy and thus will not be inclined to make corrections.

The lack of sensitivity displayed by many Westerners in the question of looted artifacts or artifacts acquired under dubious circumstances is simply astonishing. Hirst and Western artists can derive inspiration from the looted artifacts that are kept in Western museums, which they can visit anytime they want. Where can African artists derive such inspiration when iconic African objects are all in the Western world? Do Hirst and other Western artists ever ponder on how they would be able to continue their traditions or question them, if most of the iconic works of their culture were outside the Western world?

How would they like to travel to see the works of Rembrandt in Ouagadougou or view the paintings of Turner in Kwadaso, Kumasi? Doula might be the best place for works of Picasso and the French avant-garde. Timbuktu has a long tradition in keeping and guarding manuscripts and so why not send the various medieval European manuscripts and paintings there for safe-keeping? Dakar surely would be able to accommodate the works of Monet, Manet, and Matisse. Germans could surely find Dürer and the expressionists in Bamako. Abuja would be able to accommodate Goya and Michelangelo. Europeans could always visit African cities even though some African governments may be making it difficult for Westerners to visit those countries.

Westerners hardly show any remorse for the violent despoliation of Africans and many Western artists do not see any problem in dealing with looted African artifacts. The opprobrium that normally attaches to dealing with stolen goods does not appear to affect otherwise sensitive artists known for protesting at the least injustice or violation of human rights

Victor Ehikhamenor and Laolu Senbanjo have rendered an invaluable service by pointing out the dangers implicit in such an appropriation/misappropriation of an iconic figure of Yoruba culture and religion. Many who are coming for the first to this image would associate it with Damien Hirst and not Ife culture and anyone who makes a similar sculpture would be considered as imitating Hirst and not the famous Ife Head. Can Nigerians continue to derive inspiration from the traditional Ife Head without being labeled imitators of a famous English artist? Those with no idea of history or African history might think the imitators/creators existed before our people ever thought of making art. After all, many scholars, who do not speak our languages or really know much about our cultures have written that the word ‘art’ or the concept of art does not exist in African languages.

The possibility of confusion alluded to by the Nigerian artists reminds one of the confusion concerning the Ori Olokun caused by the notorious Frobenius whose dubious activities annoyed even the British colonial officials who eventually threw him out of Nigeria after his attempts to take the Olokun out of Ife and Nigeria. After Frobenius left Ife, the original sculpture found in 1938 and seen by him in 1910, had disappeared with the result that till today nobody knows where the original sculpture is. We now have three similar sculptures all called Olokun- the Olokun that Frobenius saw, the one at the British Museum and the one in the National Museum at Ife. [8]

But can we blame Western artists and others from deriving huge profits from African art and our looted artifacts? How are Westerners to know the deep and strong resentments harbored by many Africans in such matters when African representatives and institutions do not convey our true feelings to their Western counterparts whom they meet so often? Take for instance the quest for the return of the looted Benin artifacts. Apart from the petition submitted by Prince Edu Akenzua to the British Parliament in 2000 and the requests in 2009 to the Field Museum, Chicago, and the Chicago Art Institute, we have no further actions or written requests by Nigerian institutions. Yet every Nigerian Government and Parliament has proclaimed its determination to bring home Nigerian artifacts from abroad. Nobody seems to be concerned with the implementation or otherwise of Government and Parliamentary decisions. Accountability does not seem important for many.

Others are busy creating the illusion that Nigeria has been very successful in its policy to recover its looted artifacts from Western museums and institutions when in fact not a single artifact of the well-known Benin bronzes or the Ife sculptures has been returned from any western institution as a result of Nigerian efforts. It is not difficult to understand the motive behind such illusory games.

Some Africans regard as friends States that are illegally holding on to our looted artifacts. But are friends those who steal and hold onto our looted artifacts for hundred years and stubbornly refuse to return any? The definitions of friend and friendship would have to be re-examined in the light of this adamant refusal to return what are undoubtedly stolen objects. Those who meet regularly with representatives of those States at meetings on restitution that have so far not brought any tangible results may regard them as friends but are they also friends of the African peoples? One may legitimately doubt this. Some European States and officials have stated in writing that their African counterparts have not requested the return of looted artifacts such as the Benin Bronzes and no African State or officials have challenged this.

Three crown heads: left is the one in the National Museum in Ife, in the center is the one in the British Museum and on the right is the one Frobenius saw but disappeared after his departure from Nigeria.

The protest by Ehikhamenor and Sebanjo should encourage others to do their work and protest loudly whenever necessary. The bankrupt policy of quiet diplomacy must be finally laid to rest in the interest of good Afro-Western relations which have so far been characterized by one side calling the shots, deriving all the advantages and the other side, feebly and quietly nursing its resentments. When somebody steps constantly on your foot and you smile continuously at him, why should he remove his foot? Decolonization does not appear to have gone far in the area of museums.

Perhaps after this controversy on the use of a classical Yoruba image, Damien Hirst and other Western artists will pay attention to the continuing exploitation of African art resources and join forces with those claiming the return of looted African artifacts. They should do this not only in the interest of African artists and in solidarity with their colleagues. Think about what art, in general, is losing because African artists are deprived of the tools that are available to other artists elsewhere. How are they to develop in the absence of the iconic objects of Africa art? Even Westerners must recognize at one point that the continued illegal holding of the artifacts of other peoples must stop.

But African intellectuals, museums, and their governments cannot just fold their arms and expect Westerners to do the right thing. Five hundred years of relationship with the West have taught us a few lessons about Western nations and States that some pretend not to recognize: our artifacts will not be returned until our governments and institutions show determination to solve this problem finally. Increased pressure will be required. Since cultural institutions have so far not been able to recover our looted artifacts, African governments, in particular, the Foreign Ministries, should take over this subject and negotiate for their return of the looted national treasures.

As usual, when African interests are involved, many are silent who should be talking but as soon as there are signs of some success, they will announce loudly that they were working silently for our cause and regard the slight hope of success as an effect of their silent diplomacy. We believe everybody should come out now and state where they stand on the misuse of classical Nigerian art images and support the quest for the return of our looted artifacts.

A Biography of the Forgotten (2017), Victor Ehikhamenor, Nigeria Pavilion, 57° Venice Biennale.

Peju Alatise, Flying Girls (1975)

Ilé ahun là npa ahun sí. Yoruba Proverb.

Reposted with permission from Penmbazuka.org. To read the original article, click here.

End Notes

1. Wole Soyinka – Nobel Lecture, This Past Must Address Its Present, December 8, 1986. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1986/soyinka-lecture.html

2. L. Senbanjo, “A Letter from one Artist to Another.”www.okayafrica.com/in-brief/laolu-senbanjo-damien-hirst-nigerian-art/

Damien Hirst accused of copying African art – CNN.com

www.cnn.com/2017/05/10/africa/damien-hirst-appropriation-venice…/index.html

Damien Hirst Accused Of Appropriating Nigerian Art, Whitewashing …www.huffingtonpost.com/…/damien-hirst-nigerian-art_us_5911b952e4b0e7021e9b1…

Damien Hirst Accused Of Plagiarizing Nigerian Ile-Ife Ancient Sculpture

www.nairaland.com/3802214/damien-hirst-accused-plagiarizing-nigerian

Damien Hirst Controversy at Venice Biennale – The New York Timeshttps://www.nytimes.com/2017/…/arts/…/damien-hirst-controversy-at-ve…..

It seems Hirst himself is not easy with those he considers to have violated his copyright. Damien Hirst ‘threatened to sue teenager over alleged copyright theft …www.dailymail.co.uk/…/Damien-Hirst-threatened-sue-teenager-alleged-copyright-theft.

3. See annex below.

4. Jacob Epstein, Let there be sculpture, (Kindle Edition) Chapter 17, African and Other Primitive Carvings.

5. Wole Soyinka, “This Past Must Address Its Present,” Nobel Lecture. The great Ekpo Eyo, leading authority on Ife and Nigerian art, writes that Frobenius was astonished by the quality of Ife sculptures and observed that they were “eloquent of symmetry, vitality, a delicacy of form directly reminiscent of ancient Greece and proof that once upon a time, a race, far superior in strain to the Negro had settled there”. Ekpo Eyo, Two Thousand Years of Nigerian Art, Ethnographica, London, 1977, p.100

Frobenius on arrival at Ife set about to collect artefacts but even the British colonialists had to restrain him in his collection frenzy. He wanted to take away a crowned head, “Ori Olokun” but was prevented from doing so by the British colonial administration which had received complaints from people of Ife about the activities of the German ethnologist. Still he managed to take many artefacts away that are now in the Frobenius Institute in Frankfurt, and in the Ethnology Museum, Berlin, Germany. Glenn Penny writes in his book, Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany, (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 2002, p.116.) as follows:

“During his travels in Nigeria in 1911, Frobenius came into direct conflict with the British authorities concerning his collecting policies in what has come to be known as the Olokun Affair. This incident developed following complaints by the inhabitants of Ife, the sacred capital of the Yoruba country in southern Nigeria that Frobenius had mistreated and deceived them, and had taken away religious objects without their consent. The principal item in dispute was the bronze head of the god Olokun, which Frobenius claimed to have “discovered” in a groove outside the walls of Ife, but which the town’s inhabitants accused him of stealing. As a result of the complaints, which followed Frobenius’s departure from the city British authorities summoned him before an improvised British court and eventually forced him to return many of the items he had acquired from the area”.

The original “olokun” that Frobenius saw in 1910 has mysteriously disappeared. Ekpo states: “The original “Olokun” head described by Frobenius is now represented only by a copy; no one knows where the original is. It is not impossible that Frobenius could have arranged for its subsequent replacement with a copy.” Ekpo Eyo, and Frank Willett, Treasures of Ancient Nigeria, William Collins, London, 1982, p. 11

Edith Platte and Musa Hamdulo write in Bronze Head from Ife, (The British Museum Press, 2010, p. 42): “Frobenius was an uninvited if highly experienced, explorer and ethnologist, visiting Ife for just a few weeks and provoking arguments with most of the people he encountered. It is quite possible that he took the head and left behind a replica, as it was suggested in negotiations with the Oni at that time. However, it could also be the case, as suggested by Willet, that the reproduction was made sometime between 1910 and 1934, when it was brought to the palace for safekeeping”.

It seems to us though, that somebody in Germany and perhaps in Nigeria, must know where the original Olokun is. German scholars and institutions are well-known for good record-keeping. We would be surprised if the Ethnology Museum, Berlin, where at one time all artefacts brought into Germany from overseas had to be sent, had no record of the Olokun. And what about Frankfurt, the home town of Frobenius who made a large gift of 4700 artefacts to this town? Would they not have a record of the famous Nigerian sculpture that impressed him so much that, he erroneously thought it could only have been made by a lost Greek tribe? Has Nigeria reported the loss of this famous piece to international institutions such as Interpol?

6 .Kwame Opoku: Declaration On The Importance And Value Of The …www.africavenir.org/…/kwame-opoku-declaration-on-the-importance-and-va….

7. 2010 Allen Lane, p.406. For a view of MacGregor’s book, see K. Opoku, A History of the World with 100 Looted Objects of Others: Global Intoxication?

https://www.modernghana.com/…/a-history-of-the-world-with-100-looted-objects-of-

8. Platte and Hambolu, op. cit, pp.13-16.

9. ‘One should make a stand in defence of one’s rights and property, even to the death.” Oyekan Owomoyela, Yoruba Proverbs. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 2005, p.429.

Head of Obalufon, Ife, National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kwame Opuku.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.