In Nasiriyah, a group of local actors have been using a special sort of open-air theatre to encourage locals to come up with solutions to the country’s most pressing political problems.

The actors took the performance to the streets of Nasiriyah.

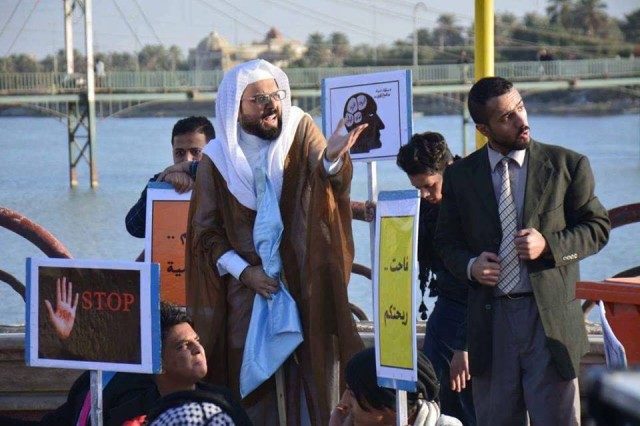

It was an unusual scene in the southern Iraqi city of Nasiriyah last August: A crowd had lined up to watch a group of actors leaving a school auditorium, the actors dressed as clowns, clerics, cleaners, tribal elders, and journalists, among other things.

Carrying signs similar to those held by demonstrators who protest for better state services and against corruption in Iraq, the troupe headed for a public square near the Euphrates river, where they would put on their second performance.

This was Iraq’s version of “the theatre of the oppressed” a form of political theatre created by the Brazilian director, Augusto Boal, in the late 1970s, the director of the theatre group told NIQASH. In Nasiriyah , a group of 20 young amateur actors had taken part in a two-week workshop about this form of theatre and they put on several plays around Nasiriyah, often surprising unsuspecting locals. There were reports of audience members jumping on stage when the actor’s courage failed him.

In this kind of performance, director Yasser al-Barak explained, the play usually revolves around an issue controversial to the community that is observing. The play stops without a real conclusion and the spectators are encouraged to participate and complete the act.

“In the theatre of the oppressed, we are at the mercy of the audience and their interaction with our ideas as well as their enthusiasm to take part,” al-Barak says.

“This kind of theatre allows us to abandon the stage and take it to the audience,” enthuses Ammar Neameh Jaber, a local writer, actor, and member of the theatre group. “In factories, on the street, to the market. It really has an impact and it influences people.”

On a personal level, Jaber was pleased to have been able to test out his skills at improvisation.

The first play put on was based on a text by famous Syrian playwright, Saadallah Wannous that was adapted to accommodate Iraqi reality. It was performed over three days and got an enthusiastic response from locals who saw it.

“At a certain moment in the play the actors are unable to tell the truth to their tyrant king,” al-Barak explains the script. “It is at that moment that the audience felt inclined to contribute.” There were reports of audience members jumping on stage when the actor’s courage failed him.

The second play was one written by local playwright Jaber himself and was the subject of some criticism by locals. They were offended that the play implied that religious groups were trying to prevent popular demonstrations in Iraq because these did not serve their interests. But, as the theatre group said, that meant that the play had its intended effect: It was supposed to encourage a debate on public protests, their challenges, and their potential.

“What was most important to me was the way the theatre of the oppressed tackled social and political issues important to the Iraqi reality, but in an artistic way,” says young actor Mohammed Nour, who took part in the performances. “They made people think – rather than waiting for the director and playwright to give them all the answers.”

The actors also got a lot out of it personally. The single female participant in the workshops, Sabreen al-Husseini, says it helped her a lot as she navigates the cultural pressures in a mostly-conservative city like Nasiriyah. “It changed the way I deal with other people,” she notes. “I was able to help them reach their own conclusions.”

“These performances of the theatre of the oppressed in Iraq, which are new to Iraqi audiences, see people getting involved far quicker because they discuss everyday problems, ones that directly affect people’s lives,” says Haider Ouda, an Iraqi playwright. “And they do it with some irony and cynicism.”

This post originally appeared on Niqash on August 28th 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ahmad Thamer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.