Gandhi has a lot to answer for. I don’t mean the saintly campaigner for Indian independence, who makes a guest appearance in Tanika Gupta’s new play at the indoor theatre at Shakespeare’s Globe, but the image of his resistance to British rule. According to this myth, propagated in films such as Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi in 1982, the Mahatma was so convincingly non-violent that the British simply gave up their imperial rule and granted India independence. This is a myth of convenience, one that flatters the Brits while distorting the truth.

In fact, the battle for Indian independence was a bloody road, involving armed struggle as well as pacifist non-violence. And it’s a story that Gupta knows very well. In 1930, her great uncle, Dinesh Gupta, participated in the assassination of the British Inspector General of Prisons in Calcutta. The attack by three young Bengali men took place at the Writers House, the administrative heart of the Raj, and was a suicide mission. After they had shot the Inspector General, they took poison and shot themselves in the head. Dinesh, however, survived and was nursed back to health by the British, and then executed in 1931.

While in prison, Dinesh wrote some 92 letters to his family, and these form the basis of Gupta’s play, Lions and Tigers. She imaginatively recreates his relationship as a bright 16-year-old Bengali to Kamala, his childhood friend and later sister-in-law (she married his older brother Jyotish), then shows his radicalization as he becomes a revolutionary freedom fighter. Influenced by the ideas of Subhash Bose, leader of the radical wing of the Indian National Congress, Dinesh and his friends Badal and Binoy gradually realize that they must use violence to rid India of the British colonizers.

Gupta has created a convincing fictional world of a group of young patriotic idealists who are determined to fight for their country’s independence. She fills in the gaps in the historical record by creating the character of Bimala, a middle-aged nationalist India woman who has survived incarceration and torture by the British on the Andaman Islands, a forgotten episode in the inglorious annals of Empire. Her female voice brings the suffering of the women who fought for independence to the fore, but also raises some troubling questions: if the young men were “groomed” by a “mastermind”, how freely did they commit their act of political killing? Is the implication that all young modern-day terrorists also need to be led by an older teacher? Are young people unable to act on their own?

Of course, you can understand the pressure of Gupta’s family members to adopt the attitude that their youngsters were duped by older militants who should have known better. And the play quotes a key phrase used by Gupta’s grandfather, a doctor, about the whole episode: “Dinesh should not have killed, and he should not have been killed.” It’s a beautifully even-handed sentiment and has flavored Gupta’s retelling of the story, which is well balanced and sympathetic to all sides. There are no cardboard baddies here. Even Charles Tegart, Chief Commissioner of Calcutta police and an advocate of torture who went on to work in Palestine during the Mandate, comes across as a rounded human being (although an unpleasant one).

In particular, Swann, the superintendent of Alipore prison and Dinesh’s jailer, is portrayed as an entirely sympathetic personality. Like Tegart, he is Irish and so there is a certain shared awareness of British colonial history. But, unlike Tegart, he is not a sadist, and although he puts Dinesh on the spot for acting recklessly and irresponsibly, he never gratuitously abuses him. He does, however, point out the costs of radicalism: Dinesh’s father and brothers all lost their jobs because of the assassination. Likewise, Gupta sketches out the bigger picture by showing discussions involving Gandhi, Nehru, and Bose about the right strategy for the struggle: is Gandhi’s non-violent civil disobedience (most notably the Salt March) a better path than Bengali violence?

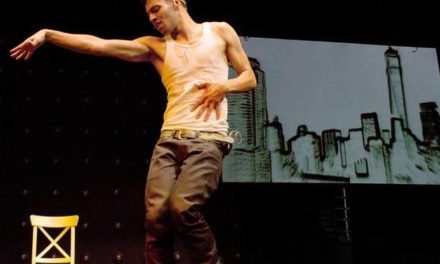

Every revolution has to confront these problems, and the justice of any cause does not guarantee the right answers to questions of tactics. But Gupta’s main focus is on Dinesh (played with the calm authority of idealism by Shubham Saraf), and on his activism, and some of the best scenes in this rich and eventful play show him and his friends practising Indian martial arts. The seriousness of the subject matter, especially now 70 years after Independence, is lightened by a vein of wry humour in what can sometimes seem like a dark story. The scenes demonstrating British torture methods and executions are horrible.

Gupta has told this story before, in 1995 with one of her first plays, Voices on the Wind, so Lions And Tigers is a bit of a homecoming. She has found a good director in Pooja Ghai, whose vigorous and fast-moving production, designed by Rosa Maggiora (who drapes the stage at the start with a huge imperial Union Jack), conjures up a picture of the Bengal Youth Volunteers as well as being an eloquent statement about the role of women in Indian society: while Bimala is a strong dominating presence, Kamala has to grow through her experiences, which at first limit her education and confine her to domesticity.

Joining Saraf are Raj Bajaj and Jaz Deol as his comrades, who in their best moments convey the sweet excitement of liberation, Shalini Peiris as Kamala and Tony Jayawardena as Jyotish (and Bose). Sudha Bhuchar strongly conveys the experiences of Bimala, Adam Best makes Swann completely sympathetic, and Jonathan Keeble is a sinister, softly spoken Tegart. Esh Alladi plays Gandhi and Deol doubles as Nehru. The cast also share other incidental parts, while Arun Ghosh’s excellent music helps the atmosphere of a candlelit space which, with its Renaissance decorations, would not be my first choice for this play. Yet the net effect is gently beguiling. This is a moving and intelligent political play whose subject of sacrificial violence remains immensely relevant and whose central characters are wonderfully evoked.

This post first appeared on Aleks Sierz on August 29, 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.