At the center of the large wooden barn is a makeshift altar, wrapped in gauze and adorned in flowers, candles, and partially constructed mannequins. A voice fills the broad, earthy space, washing over the many silver-haired heads of the audience. The voice tells of a mother instructing her children that they could, “be any color flower we wanted to be.” As the voice speaks, the lithe body of performer Travis Coe shifts at the foot of the altar, ready to explore and expose who he is, where he is going, and what flower he wants to be.

Coe describes this new piece titled SUGA, as “a ritual performance/life ritual”, and the piece has all the trappings of some spiritual exploration. Ashfield, Massachusetts-based Double Edge Theatre has provided the fertile ground for Travis to develop this work and it is a fascinating piece of self-exploratory theater that left much of the audience inspired, filled with questions, and had me asking about the nature of “ritual” in such spaces, wondering: who is ritual for? And what is the audience’s role in such ritual if the symbols, practices, and purposes are unclear to them?

For the average audience of Double Edge Theatre, this type of imaginative, exploratory performance is nothing new. The company has carved out a unique place for themselves in the contemporary experimental theater world. Their work is known for puppetry, movement, song, and an energetic inventiveness that has earned the company international acclaim. Sitting on a 100-acre farm in the hills of Western Massachusetts, Double Edge regularly nourishes their small community with new work, while engaging a cohort of students from around the U.S. who train at the company’s theatre. Travis Coe came to the company three years ago as an intern and used the organization’s spaces to slowly develop this work. Double Edge founder and SUGA director Stacy Klein told the audience that she was impressed by the continual effort that Travis put into developing the piece and she agreed to direct the production a few years into the process. SUGA comfortably reflects the experimental energy that has marked Double Edge Theatre’s work these past 37 years.

In SUGA, Travis Coe explores identity in all its forms: historical, cultural, gendered, sexual, and artistic. The audience experience of these identities begins before the production, outside the performance space in an art gallery, filled with four exhibitions for inquiry. One table displays books that served as inspiration for the piece. The books include works by James Baldwin—who Travis Coe identifies as his “spiritual father”—and art books of Robert Mapplethorpe, with photos of Coe on the wall above the table, done in homage to Mapplethorpe’s stark, figurative erotic work. Another display provides various maps, photos, and ephemera of Puerto Rico, Belize, and Nicaragua. The third table is called the “Welcome Table” and contains photos from Coe’s family and childhood. The fourth and final piece is a corner altar with a painting reminiscent of Coe hanging above the space. It is a corner for contemplation and peace and is the perfect encapsulation of the work to come: spiritual, fueled by a search for identity, and centered on the artist.

In the performance barn, Coe eventually emerges from beneath the altar in a loincloth, trailed by a long sheet of gauze. What unfolds over the piece’s 45 minutes is an explosion of movement, spinning, climbing, almost flying—all underscored by gospel music, Candomblé rhythms, and spoken poetry. Travis explores his spirituality by dancing with bells at his feet, laying offerings and prayers at the altar, self-flagellating with branches, and placing rocks at various spaces in the room. Masculinity and sexuality come to the fore in an audio excerpt from Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room and a shadow-play sexual encounter between Coe and the torso of a male mannequin on a bare, rusty bedframe. That moment unfolds into what seems like a death rite, with Coe dragging the torso in the bedframe across the playing space and covering the body with flowers—though that moment’s intention wasn’t totally clear to me. Much of the piece engages with the variety of obstacles that Travis must overcome, all indicated by exhausted running in place, climbing, and reaching.

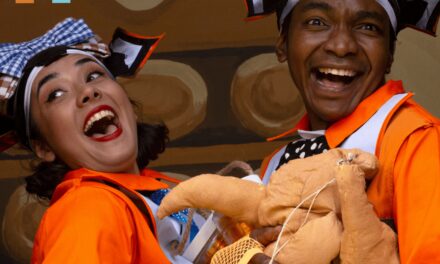

Travis Coe in SUGA at Double Edge Theatre. Photo source: Double Edge Theatre.

The ecstatic energy of Travis Coe’s breathless performance reads as a spiritual experience, accompanied by a glut of symbols and rites, many of which were not completely legible to the audience. And though legibility is not necessarily the most important aspect of the theatrical experience—think of director Robert Wilson’s frustration with audiences and critics demanding a “meaning” to his work, and his query in reply, “If you see the sunset, does it have to mean something? If you hear the birds singing, does it have to have a message?”—I wonder about the ritual aspect of the piece. If SUGA is, as Coe and director Klein describes, a “ritual performance/life ritual”, what does that mean in this context? As a critic, I take the artist at their word, and as a person curious about human spirituality and religious constructs, I take the word seriously.

To be fair, this production’s “ritual performance/life ritual” descriptor is in conversation with a variety of young contemporary performance and experimental theater artists who are similarly defining their work as “ritual.” Such adoption of the phrase sits alongside the current reexamination and acceptance of branded “magics.” Artists are presenting works that explore “Black Girl Magic”, Latinx Magic/Brujería, and “Queer Magic”—to name a few. These “magics” and “rituals” function as criticism of the blandness of daily life, a rejection of hegemonic social/cultural/religious structures, and a search for the specialness and spirituality in one’s own identity. It is fascinating to watch artists wrestle through these ideas, and I am glad that organizations like Double Edge Theatre are giving space for such questions to arise from artists like Travis Coe.

The ubiquitous usage of “ritual” as a descriptor has come in waves in theatrical circles and I am certainly not the first to ponder its usage. In 1976, author and theatrical scholar Anthony Graham-White questioned the use of the term “ritual” when employed by the Living Theatre, the Performance Group, and the other various experimental theater companies appearing in the mid-1970s. Differentiating from the literary definition of “ritual” as repeated, almost quotidian acts—which is decidedly not what these experimental theater companies were aiming at—Graham-White leaned heavily on the anthropological definitions of the term as “a performance on behalf of, but not necessarily by, the whole group or community that expresses and enforces some of its deepest values at a time (usually) of change in a seasonal cycle or in the longer cycle of a man’s life.” There are elements of this that SUGA certainly encapsulates, especially in the latter part of the definition regarding the cycle of a man’s life; in this case, Travis Coe’s.

Where SUGA doesn’t quite fit into that definition is in the reflection or acceptance of the whole group or audience’s “deepest values.” I say this because, looking around the barn at the graying or snow-white heads of a majority white/Caucasian audience at Double Edge Theatre, I questioned how much of SUGA’s values were passed along or, at the very least, understood?

Thankfully, Graham-White hasn’t had the final say in the defining of “ritual” in performance. In 1989, J. Ndukaku Amankulor wrote a response to Graham-White in “The Condition of Ritual In Theatre: An Intercultural Perspective.” Scholar of Nigerian theater practices, Ndukaku Amankulor found Graham-White’s definition of “ritual” as too narrow and possibly resultant of a negative Western interpretation of the word. He proposed that “a new interpretation is needed” for the word in theatrical contexts. Ndukaku Amankulor pointed to the process of building the production as a better definition of “ritual”, and proceeded to compare the elements of rehearsal and presentation as a form that itself hews closer to the accepted definition of the word “ritual.” It is a fascinating concept that is worth considering in the context of SUGA and how director Klein has described the grueling but rewarding creation process alongside Coe.

However, one other instructive element of J. Ndukaku Amankulor’s argument is the role of the audience. He says:

In any culture the world over, the spectator must be educated in the process of a performance before he or she can participate meaningfully and appreciate the action. An informed spectator does not just walk into a performance unprepared, but comes with some knowledge of the pre-performance or rehearsal processes and understands his relationship to the performers in the context of the performance space.

The author is explicitly describing the artist/audience contract of performance, stating, for example, that an audience interrupting a work would be that ritual’s taboo. This statement—defining the audience’s participation in ritual merely as knowledge of how to maintain decorum in a theatrical space causes me to think again on the audience’s base of knowledge altogether. Yes, this audience of SUGA understood theatrical conventions, but what does it mean if the audience does not know or understand the function of the ritual itself? What if the purpose of the process isn’t legible? And if those values, symbols, or rites are not understood, what difference is this form of “ritual” than the experience of white spectatorship at Pow wows on the various reservations in my native New Mexico, or the uninitiated paying to experience any other ritualistic spirituality? According to Ndukaku Amankulor, the piece is still a ritual in the functional sense, but I wonder about its effectual sense.

This leads to an important and instructive element of SUGA, which is the audience gathering. The gathering occurred after Coe’s tireless performance—think of a facilitated theatrical “talkback.” Talkbacks or gatherings of this type are uncommon to Double Edge, according to Baraka Sele, the facilitator/”Respondent” of SUGA on the night I attended. Bringing Coe and Stacy Klein on-stage, Sele asked questions about process—or, as Ndukaku Amankulor would call the “ritual”—and unpacked some of the symbolism for the audience. At one point, Sele asked about an affecting moment in the performance when Coe was on the “auction block.” It was a moment I am sure to have either missed or did not read in my interpretation, causing me to wonder if I was alone in misreading much of the work—which is a genuine possibility. When the artistic team talked about Santeria, the Afro-Cuban spiritualist practice, and the symbols of the practice on the altar, there was a few grunts and hums of appreciation from the older audience for the clarification. What else didn’t they get? Or what did they understand?

Stacy Klein commented in the response/talkback that the work on this production is not done and that it will continue to develop and grow, which, in a sense, makes it feels a little unfair for me to proffer any criticism of a work-in-process such as this. But I am contented to share the final question from an audience member during the response, which somewhat sums up my thoughts. A woman raised her hand and kindly expressed gratitude to Coe for his bold performance. She hesitated for a moment before asking, “What is the thing you want us to leave with?” I didn’t interpret her question as, ‘Please give us your final thoughts before we go’, but rather as, ‘What information are you trying to give us in this performance?’ or ‘What do we need to know?’ It was a question I had myself, but am confident that, as Travis Coe continues to publicly explore himself and unravel aspects of his identity, there are further roads to traverse for this capable creative team, with rituals to share and clarify for future audiences. That flower is still blooming into whatever color it wants to be.

SUGA will be traveling to CRASHBOX by Rude Mechs in Austin, TX from March 4-6. Information and tickets can be found here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by James Montaño.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.