There has been a dearth of original Filipino plays gracing the theatre season of major theater companies in the past few years. In times like these, theatre managers turn to canonical works of literature as materials than can be commissioned for translation and adaptation.

Tanghalang Pilipino brings John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice and Men to the Cultural Center of the Philippines’s Tanghalang Huseng Batute (Studio Theater) stage retitled Katsuri from 5 to 27 October 2019.

In Bibeth Orteza’s adaptation, the California farmlands of Steinbeck are transported to the heartland of feudal exploitation in the Philippines— in the haciendas of Negros Occidental, where the most inhumane conditions of planting, harvesting and milling sugar in Philippine feudal history are known.

In Orteza’s and director Siguion-Reyna’s Katsuri, representations of sacada (sugar farmers in the island of Negros) veer away from the typical, almost iconic, images of the sacadas as rendered by the social realist painters of the 70s— hoodied heads, a pair of eyes peering from layers of cloth wrapped around their faces, and hunched bodies. Katsuri’s stage harbored a diverse group of farmworkers housed in a kuwartel (quarter, usually of horses), carrying their own physicalized expressions of angas (spunk), a thin cache of spunk that fizzles out when the hacienda foreman and his overbearing son swing by to make routine inspections.

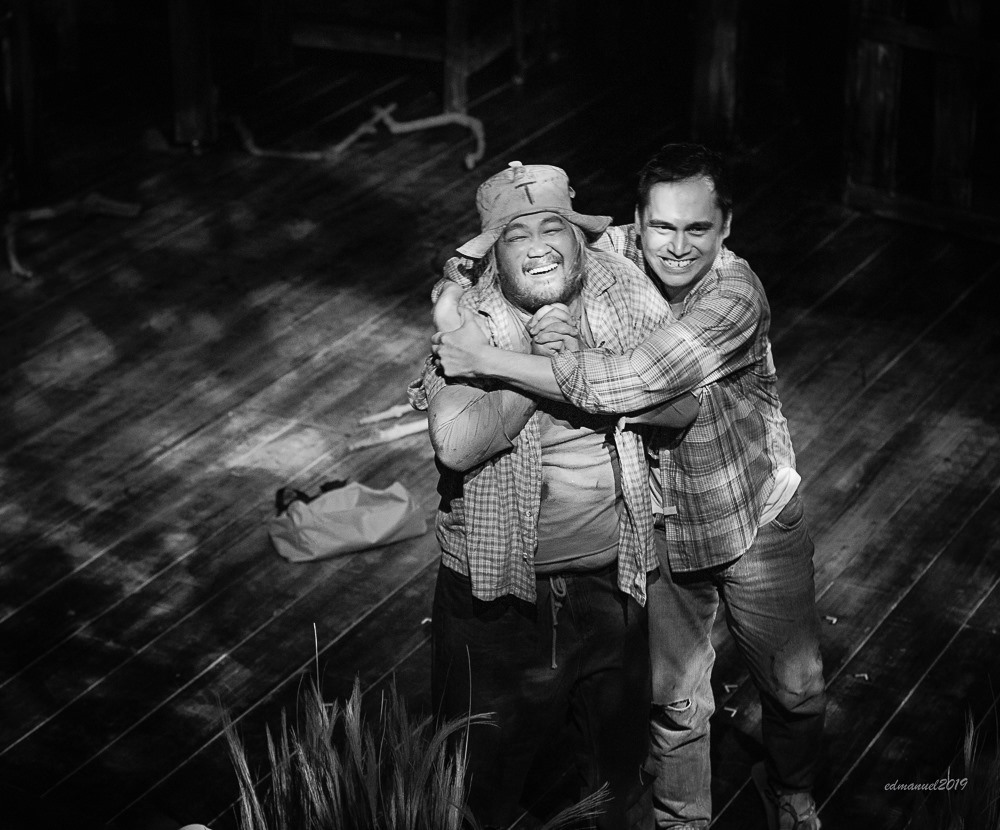

The brothers George (played by Marco Viana) and Toto (performed by Jonathan Tadioan; Lennie in the novel) in the Philippine stage adaptation of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. (Photo: Courtesy of Edgardo Manuel)

Orteza’s adaption is largely narrative-led, adhering closely to Steinbeck’s structure, plot points, and an ensemble of characters, even the crude stereotype of a wily woman out to seduce the men in the hacienda. The heart of the story is the tandem of George and Toto (George and Lennie in the Steinbeck novel). George takes guardianship of the feeble-minded Toto, as he feeds him with love and loathing, toughness and tenderness while treading precarious lives on subsistence wages and the meager crumbs from the kitchens of the hacienda foreman.

One of the highest points of the play: George ready to pull the trigger. (Photo: Edgardo Manuel)

Toto is played by Jonathan Tadioan who, as expected, shares a bigger fraction of the acting plaudits as he completely transforms into a child living inside the burly body of a farmhand deprived of the mental acuity to comprehend that whatever direction they turn to, it will be a dead end. Tadioan and Viana bring to stage a synergy that will long be remembered as a shining moment in Philippine theatre.

Left-wing politics embellish this Steinbeck adaptation, with the referents pulled in for local context— haciendas as emblematic of centuries-old feudal oppression, the economic exploitation arising from the power structures and ownership, and summary executions by a man in military uniform roaming the peripheries of the stage. This is Orteza’s way of re-telling a story, a gesture toward the potency, relevance and timeliness of the source material to the harsh realities of the Philippines.

However, in this case, the referents are not well integrated into the entire narrative. At best, they remain in the peripheries of the writing, tweaked in the dialogue, presented as images of violence like the fatigue-clad man, and as pistol shots ringing in the air. Orteza’s loyalty to the material, even to the misogynistic implications of calling a bored woman as pokpok (a woman hired for paid sex) renders the entire oeuvre as fragmented, made even more so by Siguion-Reyna’s heavy-handed approach to storytelling.

Which brings us to ask: how are adaptations of canonical works of literature best carried out?

Is it merely appropriating local spaces and categories to replace the referents in the original work? Is it about adding new elements such as militarization and extra-judicial killings to amplify political agenda? Nothing wrong with political agendas; in fact, the radical traditions of world literature can be appropriated by local theatre productions to buoy up critical and creative engagements. It can even be more radical and edgy as adapting by “resisting” the original story— unpacking the fractures of its storytelling, or exploring a gaze that probes the limits of the literary zeitgeist of the source material, such as Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, written in the realist tradition that defined literary production in the era of the Great Depression.

The most remarkable works of world literature and Philippine literature have always graced the Philippine stage. At a time when local playwriting seems spiritually enervated, we hope to see adaptations that can stand as oases, quenching our thirst for dramatic representations of Philippine realities in ways that are novel, fresh, tightly wrought, even bolder and militant than mere suggestions of militarization.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maria Jovita Zárate is a senior lecturer at the University of the Philippines Open University and a member of the jury of the Gawad Buhay!, the first and to date, the only award-giving body for the theatre in Metro Manila.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Jovita Zárate.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.