Winsome Pinnock has for decades been a central figure in the promotion of BAME drama not just as a minority interest, but as part of British theatre’s mainstream. She has argued passionately not only in support of all kinds of voices from the margins of society but also in favor of widening audiences for all kinds of plays. In a great body of work, from the modern classic Leave Taking (1987) to her Royal Court plays, A Hero’s Welcome (1989), Talking In Tongues (1991), and Mules (1996), and never forgetting her under-rated One Under (2005), she has developed an emotional generosity to her characters, an innovative linguistic palette and a willingness to experiment with form that characterizes the best writers. Yes, she’s obviously one of the most significant playwrights of the entire postwar period.

First seen at the Liverpool Playhouse in 1987, Leave Taking transferred to the National Theatre, making Pinnock the first black woman to have a play staged at this flagship. And now this overdue London revival, brilliantly directed by Bush supremo Madani Younis, more than justifies the play’s legendary reputation. Set in North London, the play is a family drama that explores the relationship between Enid Matthews, a fortysomething single mother originally from Jamaica, who lives with her teenage daughters, the rebellious Del (18) and the studious Viv (17). Worried by the fact that Del stays out late, and suspecting that she might have got herself pregnant, Enid takes her to see Mai, an obeah woman in Deptford. But although Mai can do Caribbean soul-healing, she’s not at all keen on giving maternity advice.

As the conflict between mother and daughter intensifies, Enid gets both advice and some hard truths from Brod, an old friend of the family. But although Enid insists that “England be good to me,” he reminds her about colonial oppression: “Imperialism. Vampirism.” Both of them are conscious of just how hard their lives in the West Indies were, remembering the poverty, dirt, and desperation, yet although England is an improvement, it is also a place that has scarcely been welcoming: both have experienced extreme racism. So Enid has decided to be a hard mother, to teach her daughters to be tough—because, in order to survive, they will need to be.

So Enid tells Del and Viv little about their father and nothing about Jamaica. She feels ashamed of her poor roots, although she regularly sends money home. When her mother dies in that distant place, she suffers a crisis. And it’s one that is shared by her daughters. Although both Del and Viv were born in Britain, neither feels British in the way that Enid has dreamt that they would. Their experience of racism has made them feel insecure. They are both still searching for their identities. At one point, Viv even says: “I sometimes feel like I need another language to express myself.” They experience a crisis not just of identity, but also of life plan.

Enid is a complex character with complex ideas about the migrant experience. She is proud of her own capacity to adapt to her new environment and her ability to bring up her daughters. But although Brod agrees with her, he also points out that living in England for 30 years, and working hard, has not prevented the UK authorities from treating him as an “alien” and—clearly relevant to to the recent Windrush scandal—getting him to pay for the privilege of staying in the country. His story about Gullyman, a kind of everyman migrant figure who saved a lot of money but then had a breakdown when he saw how badly he was treated, has a strong emotional punch. For Pinnock’s characters, being positive about migration is always undercut by awareness of bad experiences.

What is wonderful about the play is the slow but deep feeling that develops during the telling of the story. Gradually, Enid realizes that her whole way of responding to living in London is not right, that it denies her own pain and her own needs. At the same time, her daughters also make similar journeys. Viv comes to understand that the educational syllabus, which she excels at, makes no mention of her family’s experiences; Del, inspired by an unexpected interaction with Mai (a person she initially distrusts and mocks), discovers a quality of empathy and second sight which just might be the saving of her (casual sex and drugs will lead nowhere). Brod finally grows into a truth-teller and a catalyst for change. All of these strands are perfectly integrated with each other.

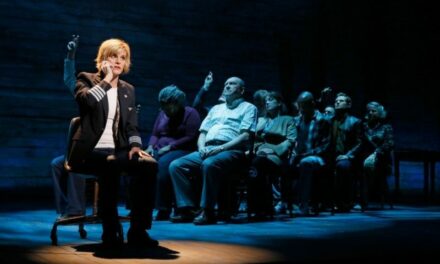

Younis’s production of this thrilling play is a joy. He has taken it and stripped away most markers of its origins in the 1980s, instead, staging it on a bare set, designed by Rosanna Vize, with only a few props such as a landline telephone, cards for fortune telling, and an old record player. The characters wear timeless costumes, and Mai is not dressed as an exotic mystery woman but appears in jeans and shirt. And there are some lovely theatrical surprises. At one point, a shower of rain falls on Enid, both a reminder of England’s dismal climate and perhaps a suggestion of a sprinkling of mercy. It is a strongly metaphorical image. Crucially, Younis has also not only encouraged his cast to enjoy the vigor and vitality of Pinnock’s text, and especially its humor, but also has made them pay close attention to its emotional truth.

Sarah Niles’s Enid makes the journey from pent-up strength to open vulnerability with enormous dignity and expressiveness: her final speech “Nobody see you, nobody hear you” moved me to tears. Likewise, Adjoa Andoh’s clever and perceptive Mai avoids all the clichés that can accrue to that role, and delivers a convincing portrait of a feisty and intelligent woman whose gift is both a blessing and a curse. Similarly impressive are Seraphina Beh (Del) and Nicholle Cherrie (Viv), who bring out the individual struggles of the daughters, while Wil Johnson’s Brod is a perfect combination of passion and comedy. With its great mix of pointed exchanges, convincing plotting, relevant issues, sense of learning from experience and emotional integrity, this is a brilliant production of a truly wonderful play.

Leave Taking is at the Bush Theatre until June 30.

This article originally appeared in Aleks Sierz on May 31, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.