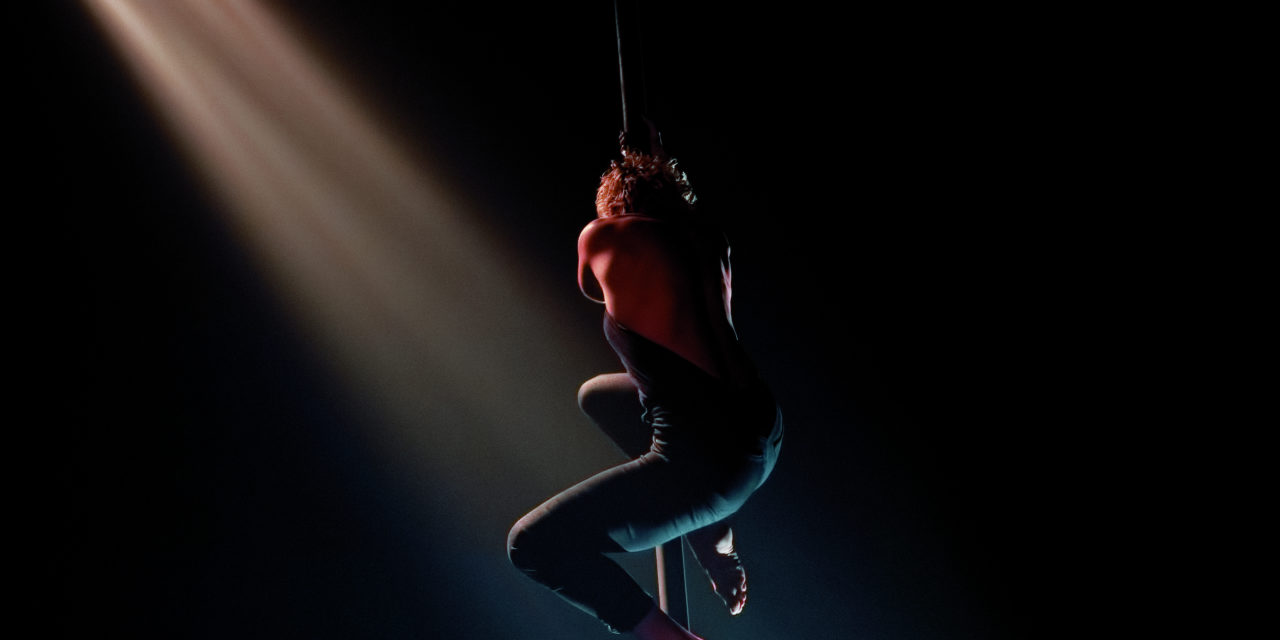

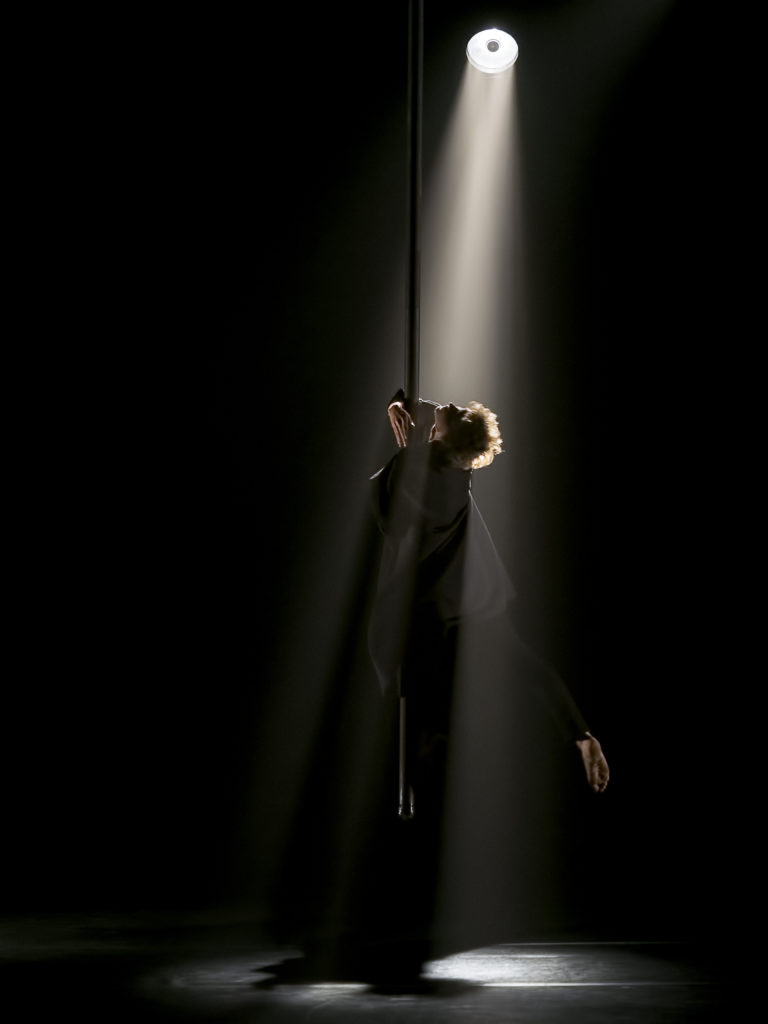

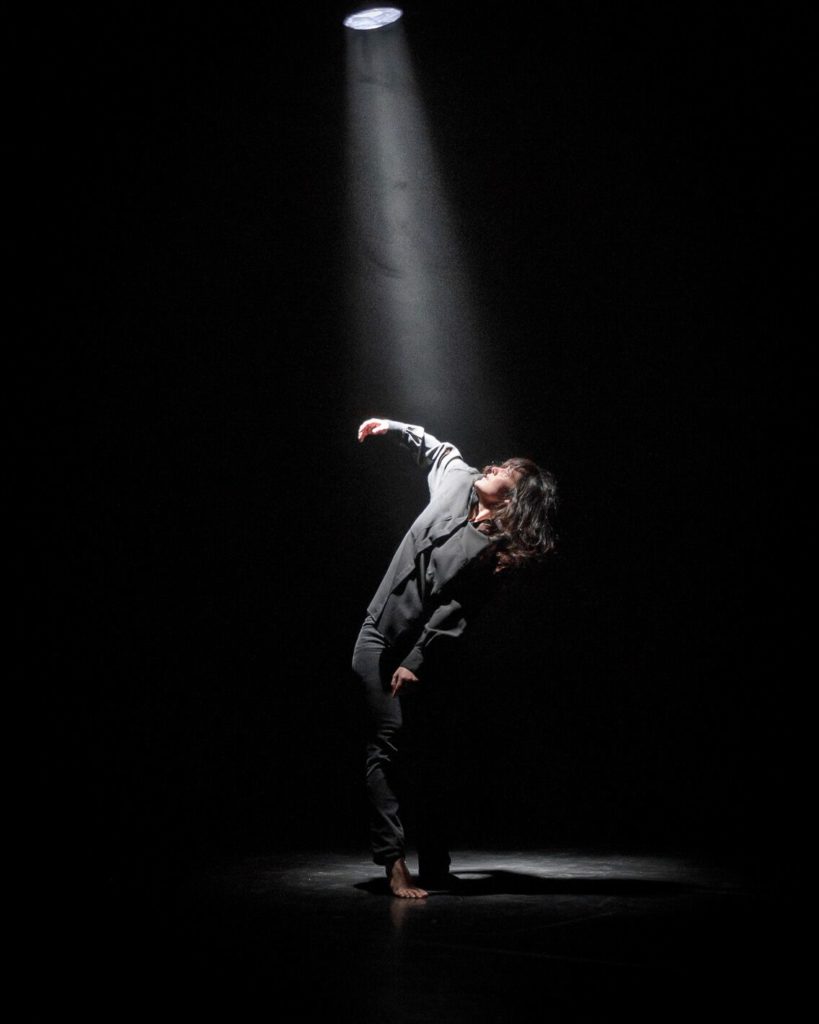

ArtsEmerson is honored to host the New England premiere of When Angels Fall, a riveting tale of flightless angels surviving in the wake of a global collapse. As a mesmerizing contortionist and aerialist herself, French creator and director Raphaëlle Boitel’s storytelling is singular, and her ability to transform space in the air to the ground with large scale illusions–and bodies streaming across the stage–is magical. Boitel brings her spellbinding visual storytelling (no words are uttered on stage) for five performances only, February 20–24, at the Emerson Cutler Majestic Theatre. Blending circus, dance, and cinema, When Angels Fall is a dystopia where the resilience of the human spirit is pitted against the sterile and mechanical. Drawing inspiration from such disparate artists as Pina Bausch, David Lynch, and her longtime collaborator, James Thierrée, this delightfully dark and entrancing theatrical premiere explores how the beauty of letting go gives us the strength we need to rise. When Angels Fall will summon laughter and awe during its harsh descent from the heavens.

Creator, Director & Choreographer Raphaëlle Boitel collaborates with Tristan Baudoin (Set and Lighting Designer) on all her artistic projects.

Photo Credit: Georges Ridel

Irina Yakubovskaya: There are seven people in the cast of When Angels Fall. Without giving too much away, could you shed some light on what they represent?

Raphaëlle Boitel: The seven people represent society. It is a group of very different people with different bodies. This is the idea, but I still want it to be very open for the audience. It could be different things. They could be the last humans or maybe they are angels, there is a lot of ambiguity. We understand that something happened, or something will happen, but clearly, they are in a closed space, and they live together. In a way, they are different. They are the last ones.

There is one old woman and one woman-child. She is the youngest one, and maybe the one that will bring more hopes. The old woman knew the world before.

Tristan Baudoin: The young woman is the one who sees this [post-apocalyptic] world as normal. She knows only this time, only this context.

Boitel: It is possible that the oldest one knew the world from before, and she stays kind of stuck there. She looks of the world of before and she doesn’t want to look at the world that she lives in today. For the young girl, the world is normal.

Baudoin: Everybody is on stage: the technicians, the dancers, the circus performers.

Boitel: Everyone is on stage, and everybody is a character; performers, technicians, there are some that are a bit nastier than the other ones. I always wanted to mix everyone on stage and not to focus so much on the performers only. Even if there is an aerial magical moment, I like to have everybody together. They kind of represent the society with all its differences. I think [the audience] will identify with someone in the show. They are so different, and they have different personalities.

Baudoin: The young woman in the show [represents] this [current, millennial] generation. She is talking to a machine, she doesn’t talk to human beings. She doesn’t even look at them.

Boitel: In fact, I’m really interested in human beings. The young people who see the show are usually very touched. [We explore] the domination of the machines and how we use them.

Baudoin: Where is the human being’s place in this mechanic world.

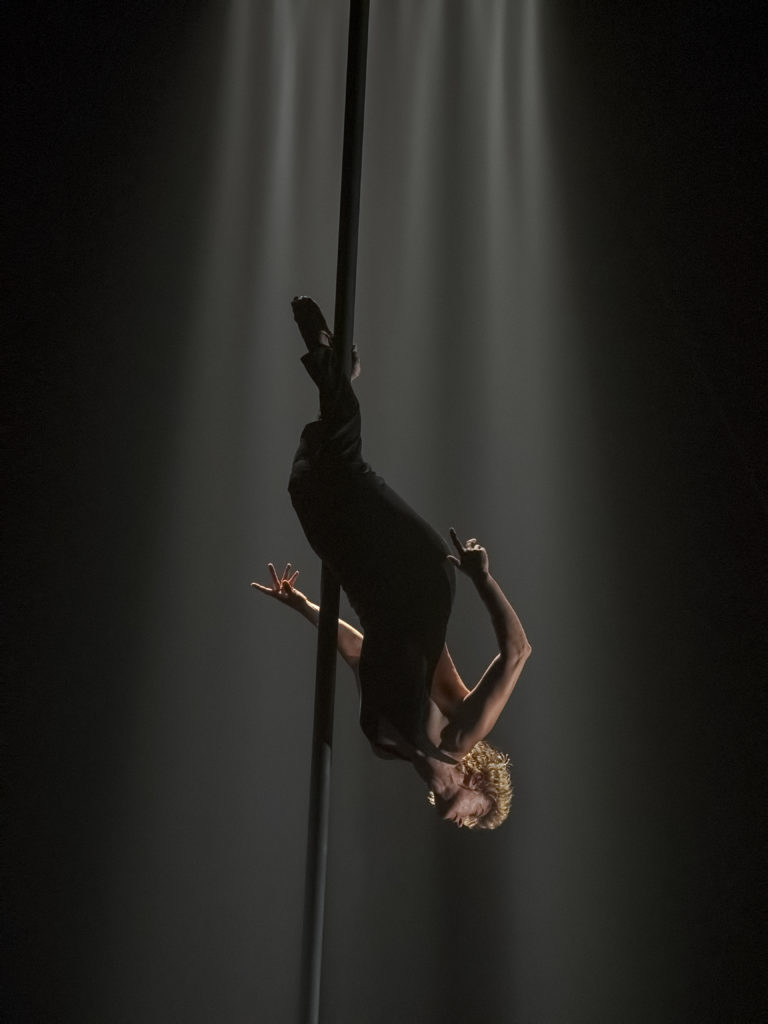

Photo credit: Georges Ridel

Yakubovskaya: How do you find poetry in human bodies when they can sometimes be disturbing in their biology?

Boitel: I think bodies are beautiful, all kinds of bodies. It’s how you are with your body. I think it is important to accept and to trust and to be concerned about our body because sometimes we also forget our body, and we are just trees without branches. Once I did a workshop with a French teacher and she said this to me: “thank you for making me realize that I have a body because I forgot I had it.” I want to remind people that we have those bodies, and our mind and body are connected. We must help each other, and we have to be in our body. And Tristan knows so well how to make a body beautiful with lighting. Tristan works with chiaroscuro, takes shadows of the body, and the lighting is moving.

Baudoin: You say all bodies are beautiful…

Boitel: …and all people are beautiful, we all have a light inside. There is a scene in the show where you see a lot of skin. It is not a love scene, the characters don’t look at each other, but they are completely together. Tristan makes the light move as if it were alive. It is not very virtuoso, but it is very beautiful. They look at each other, they need to be connected, they don’t know they are connected but they need to hold each other. During this scene, a lot of people cry, and they don’t know why. [I think] they cry of beauty. I created [the scene] just feeling it…I just feel this, and the audience feels it too, it is so deep inside what we all are. What we need. It’s a little bit like a secret garden.

Photo credit: Sophian Ridel

Yakubovskaya: As you mentioned before, the role of lighting in this show is unique. The light is also a character. The light is artificial, and yet it is alive.

Boitel: The light represents the technology, but in a way, it is quite contradictory.

Baudoin: We work together in creating our shows. You write in light, you need light to write. In this production, we went a little bit further. The light has become a character, and this character is also an observer.

Boitel: The light beautifies the body, and simultaneously in our story, it represents the third eye. It is quite contradictory.

Baudoin: It is alive, but at the same very mechanical, and something brings this machine to life.

Photo credit: Sophian Ridel

Yakubovskaya: There is someone who controls it…

Baudoin: Maybe.

Boitel: Definitely.

Baudoin: The light, it interacts with the actors.

Boitel: The technology is alive. The technology becomes very friendly with the youngest character. It is an ambiguous contrast of this machine: maybe in the world of the future, machines have some feelings. We don’t know. We don’t want just to say “Ah, the machine, the technology is not good, and it dominates,” because it can also be beautiful and friendly. It can be beautiful and also scary.

Baudoin: It is highly ambiguous.

Photo credit: Sophian Ridel

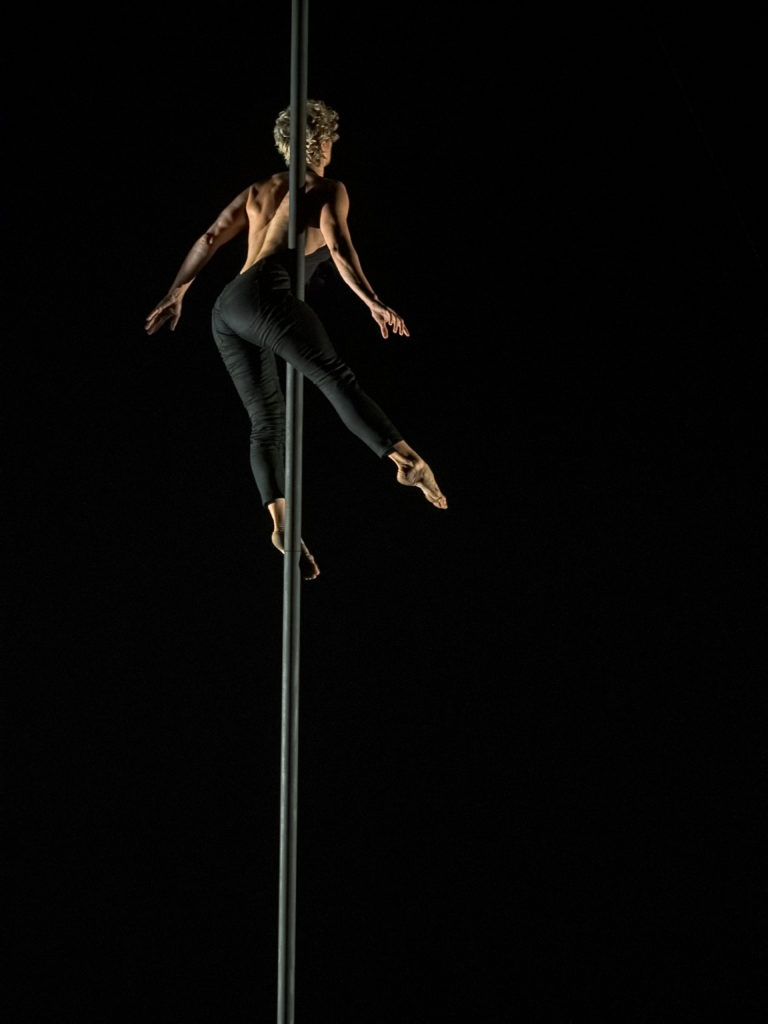

Yakubovskaya: How do you address the multidisciplinary genre of your work without getting labeled as a circus performance?

Baudoin: This is not circus and yet we use circus artists. You take them further, beyond their craft.

Boitel: This piece is maybe denser than a circus piece. But there is a quality of a circus performance. There are amazing capabilities of being in the air, of being in all extreme situations. There is a lot of circus inside because I work with a lot of circus people, but I push them to embrace dance, theatre, they function as actors. I myself have always been an actress, I’ve always wanted to do cinema since I was a kid, and then I wanted to work with my body, and explore what we humans can do with our bodies. We can dance, move, climb, fly, and that’s amazing. We can do extraordinary things, and that makes our lives more exciting. This piece should not be considered pure circus. What interests me the most is the human being, what we say about it. The body is my way of talking.

Baudoin: I also think you like working with circus artists because they have such incredible capacities and yet they are just regular normal people. They represent the metaphor that you want to share. The metaphor is that everyone can do incredible things.

Boitel: I like working with “normal” bodies. Even if I was in circus since an early age, I always had quite a normal body, with shapes. Even when I work in the opera with singers they always say to me “Wow I didn’t know I could do that [with my body].” They trust the work, and they open up. They trust each other, they dance and let it go. I could give a workshop to anyone because I like people, I like to look at the light inside.

Photo credit: Sophian Ridel

Yakubovskaya: Do you choreograph your actors, or do they contribute their ideas?

Boitel: I choreograph them, but I go from vocabulary [what they are familiar with]. For example, I’ve never done Chinese pole, so they show me, and sometimes they show me a choreographic figure, and I ask them to compose, but then I take all these elements and do the choreography. I am very open to propositions, I ask them to be implicated in the inspiration process. I ask them to propose things to me a lot. I also work from the improvisational exercises that I developed. In these exercises, I propose a theme, and we go from there. They have a lot of space to be themselves, and also find more than they thought they could do. Trying to make them leave their brain and not think too much. Often if you are too voluntary, it doesn’t work. I really search for the instinct, for the real thing that comes from the inside.

Baudoin: It is a sort of therapy.

Photo credit: Georges Ridel

Yakubovskaya: What is the biggest challenge in creating original work?

Boitel: It is very hard. We are not writers or authors. One must create everything from A to Z, even the music. Everything it a blank page.

Baudoin: Everything is original, it is difficult. We have to write on this empty page.

Boitel: When you have the idea and get excited about it, you put it on the paper, but then you do it on stage, and it does not work. Sometimes when you want to explain everything on paper, it’s very naïve. When I create, I have to listen to my instinct and to what I feel. It is really back and forth of thinking and doing. Then the light brings something else, and maybe the character proposes something I haven’t considered. It is very hard, you become crazy. Sometimes before the premiere, I keep looking for how to say and do it all without words, just with the bodies, how to express it. Even me, I have to search very deep inside, I have to go really profound. Sometimes you have to be in front of your anguish, that makes you evolve so much when you go back inside. It’s very challenging. Sometimes I would like to do a theatre play from a book because it’s exhausting to create [original work]. But it is also rewarding because you have a show that you have imagined, and of course, it is really collaborative. I would not do this alone. It is a team thing.

Photo credit: Sophian Ridel

Yakubovskaya: Was there anything new you discovered about each other as artists throughout your work?

Boitel: With every show we go further, and we have more admiration for each other. Now we don’t need to talk anymore when deciding on the lighting, etc.

Baudoin: I know what she likes.

Boitel: I know what he likes. In every show, we discover new things. It is a perfect harmony. Our identities both are reflected in the shows. It is very important. This show, When Angels Fall, expresses both of us: what we think, what we are, what we question.

Photo credit: Frank Berglund

Yakubovskaya: Tell us a little about your future projects.

Boitel: We always have many projects, new work, new shows. I’m doing a show for young audiences. I would also like to direct an opera with mixed arts. Each show is a step towards a global vision. In the end, we would like to create a place like an academy or a laboratory, a Pina Bausch-like space to do research, mix arts, and educate. Our salvation is with art and the capabilities of dreaming. New artists and mixing arts, that is what interests us. For one goal.

*(parts of the interview were conducted in French, and consequently translated into English by the author/interviewer)

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Irina Yakubovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.