For an artist known for engaging the political in his work, it’s perhaps impossible for Samson Young not to be affected by the protests that have roiled his hometown for more than three months. “I’m still trying to work as normally as possible,” says the artist and composer in an early September phone discussion.

And yet that sentence reveals just how difficult it is to just get on with it in times like these. Young’s latest show, at Talbot Rice Gallery at the University of Edinburgh, is simultaneously about and not about Hong Kong. Since the early 2010s, Young has staked a claim in the art scene for visually and sonically impressive works that investigate the multi-layered web of conflicting ideas and narratives that make up our aural environment. Young’s new exhibition, Real Music, which centers on what cultural authenticity means in an increasingly fluid world, is no less inquisitive.

Image courtesy of Talbot Rice Gallery

The exhibition was two years in the making. Gallery director Tessa Giblin had seen Young’s 2016 work Canon at Art Basel in Switzerland and, impressed with his ability to engage with the political, she invited him to exhibit at the gallery. Not wanting to parachute Young’s previous works into the space, Giblin introduced him to a bevy of university scholars with whom he could collaborate. He ended up working with the team that developed NESS, a system that can digitally simulate what a hypothetical instrument would sound like in a hypothetical situation.

“I was immediately drawn to [NESS] as my background—and my practice—is very research-based,” says Young. “It was very organic. The NESS team opened up their research to me, and I flew in a few times to learn the software, the algorithm.” What transpired was Possible Music #2, a piece where a group of speakers blasts such impossible sounds as “a bugle sound if it was activated by the fiery breath of a dragon” at regular intervals.

Aside from reflecting on Young’s continuing interest in dichotomies such as real and synthetic, authentic and fake, the piece also allows Young—who frequently engages in digital sound experiments—to ask a very specific question. “Analogue [as opposed to digital] music is often perceived as being more authentic,” he notes. “But why is that?”

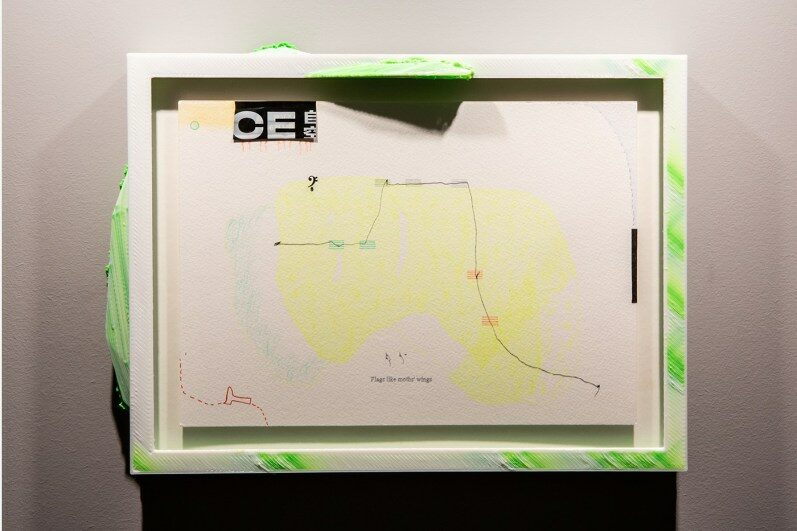

Next to the speakers, two giant sculptures of a bugle and a trumpet emerge from the carpeted floor. “They’re all modeled after actual musical instruments, but if you make them so big, they become surreal,” says Young. Another work, Sound Drawings, beckons from the gallery’s mezzanine. One of Young’s longest-running series, it translates the sounds of chirping birds, thrashing water and more into graphical notations. Sounds are seen instead of heard, redirecting our attention to the kinetic energy of the music.

Possible Music #2 simulates what hypothetical instruments sound like. Image courtesy of Talbot Rice Gallery.

The drawings at Talbot Rice are underpinned by the ongoing protests in Hong Kong. One work in particular features a graphic notation of the sounds recorded during the march on 16 June, when an estimated two million people flooded the streets. “I wasn’t going to include the Hong Kong protest, but the marches broke out [in early June] when I was making the drawings,” says Young. It was hard to ignore.

A piece from Young’s long-running Sound Drawings series. Image courtesy of Talbot Rice Gallery.

On the other side of the gallery, Muted Situations #22: Muted Tchaikovsky 5th is a familiar work, having been shown at the Hong Kong Visual Arts Centre earlier this year. Cologne’s Flora Sinfonie Orchester performs one of Tchaikovsky’s best-known symphonies, but the musical notes are suppressed, refocusing our auditory attention to the previously unheard: the sounds of pages being flipped and shuffled, musicians’ breathing, bows sweeping tonelessly over strings.

The work is—as its name implies—the 22nd iteration in the Muted Situation series. In the previous installment, Young muted the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions Choir’s rendition of We Are the World, the charity single that was widely popular after its release in 1985 but has since been criticized for being patronizing towards the global south. The critique underlying Muted Tchaikovsky 5th is a bit more subtle. Even though the symphony itself isn’t controversial, muting it calls attention to “the politics of the act of muting – by a Hong Kong composer of an old European ‘master,’” as curator Joel Stern notes in his catalog essay for Young’s exhibition. The piece asks complex questions of what it means to represent something and what it means to stay true to a musical score; after all, classical music lovers will likely recognize the symphony from its rhythms, even if the sound has been removed.

Muted Situations #22: Muted Tchaikovsky No. 5, where musical notes are suppressed. Image courtesy of Talbot Rice Gallery.

After this work, viewers pass through a corridor showing amongst others, glass vitrines containing a miniature bridge-harp, a rgya-gling (a Tibetan instrument) and a 1796 version of the popular Chinese song Molihua (“Jasmine Flower”). Given the visual dissonance between this group of works and Tchaikovsky’s 5th, these objects might be mistaken as part of the university’s permanent collection. But the mystery is solved as viewers pass to a dark room at the back, where the idea of cultural authenticity is further expanded in two videos.

In one, viewers are introduced to the history of Molihua. Young first came across the song in English diplomat John Barrow’s 1804 travelogue, in which the English statesman noted its popularity while simultaneously raising doubts about its authenticity. While Molihua purportedly dates back to the Ming dynasty, the version Barrow heard was arranged by London-based German composer Karl Kambra, who had modified the original tune to fit English sensibilities. And just like that, the old song gave way to the new and, as the artist notes, the Molihua played at major events, including the 2008 Beijing Olympics, is Kambra’s version, not the supposed original – a Chinese song filtered through a Western prism and brought back to China.

Young’s piece centers on the idea of “echoic mimicry.” Used by artist Paul Carter to describe situations of cross-cultural encounters, echoic mimicry involves a state in which someone says something and is misheard by someone else, after which that mishearing is directed back to the original person, who in turn mimics what has been said. The video essay is narrated by a University of Edinburgh professor with a thick Received Pronunciation accent – a learned accent traditionally seen to represent authority, reason, and power in Britain. Yet the sense of authority usually attributed to the accent is repeatedly undercut by the irreverent tone. “It’s serious and quite dense,” says Young. “The humor is the sugar that helps the medicine go down.”

While Young believes that there are other tunes that have gone through reappropriation, the story of Molihua was “just so peculiar” he transformed it into a funnel through which to examine the idea of cultural authenticity. “I want to ask, what is considered Chinese?” he says. “You can’t make a distinction between what is yours and what is mine. When you look at Molihua, it has already been cannibalized. It is no longer possible to make authentic objects, so to speak.” For Young, culture is always in a state of flux, and what we see in front of us—be it a song or an object—carries a fraught history.

That’s one of the reasons why Real Music strikes a chord in these trying times when so many are thinking about what it means to be a Hongkonger. What role does art play in this kind of scenario? “Art definitely has a place,” says Young, adding that he subscribes to Jean-Paul Satre’s idea that art embodies a mirror of society. “The way I see it, art is a way for me to process issues. If I stay true to that goal, there is inevitably a gap between when I make the art and when people see it, so often an ambiguity comes through.” He pauses for a moment before adding, “That’s not to say I won’t come to a conclusion about certain things. It just doesn’t appear in my art. If I take a goal-directed way of making art, it limits what I can make.”

Not that Young thinks he has the ability to do so. “I’m not a very clear thinker. You need to have your finger on the pulse but you also need to possess a certain positivism,” he says. “I’m not one of those people.” For now, he will keep on doing what he’s best at: stripping the flesh away to lay bare the skeletons.

This article was written by Christie Lee for Zolima CityMag on February 5, 2019, and has been reposted with permission

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.