The new theatre texts that have been presented in the 2015/16 season at play markets in Heidelberg, Mülheim and Berlin and on festivals of contemporary drama cannot be reduced to a common denominator, either in style or content. And they are not at all part of a trend. There is, however, a striking tendency to undermine supposed certainties and one-sided points of view by means of richness of perspectives and diversity of voices.

It is surely no exaggeration to call Yael Ronen’s production The Situation at the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin the play of the hour. For here the global situation is masterfully compressed into a local evening class. A Syrian, a Palestinian, a Jewish-Arab married couple from Jerusalem and other characters whose biographies are linked to the Middle East meet each other in Berlin. They are all attempting to learn “German as a foreign language” in an evening course. Naturally, already in the first lesson “Who are you?”, they come into conflict and fall into debates about identity that would be difficult to cope with even in the highest level German course.

The evening, developed by Ronen together with her international actors using actual biographies and experiences, opened the 2016 Mülheim Theatre Festival. The festival is one of the most important for contemporary drama in German-speaking countries; it annually presents six to seven notable new theatre texts of the season and, at its end, awards the Mülheim Dramatist Prize, endowed with 15,000 euros. Last year the prize went to Wolfram Höll, whose play Drei sind wir (i.e. We Are Three) describes the short life together of a mother and father and their new-born child suffering from a fatal trisomy disorder.

THEMATIC AND LINGUISTIC-STYLISTIC DIVERSITY

On the one hand Ronen’s up-to-the-minute German lesson, charged with her customary cliché-shattering humour, and on the other hand Wolfram Höll’s text, which revolves in language loops around a time-overarching existential (family) drama: the field in which contemporary drama of the 2015/16 season is located is encouragingly wide, both in content and in language and style. For example, in her play Zweite allgemeine Verunsicherung (i.e. Second General Uncertainty), also invited to the Mülheim Theatre Festival, Felicia Zeller plunges her characters into exposed situations of self-presentation – for instance, on the red carpet, in profound and witty self-doubt, while Thomas Melle’s Bilder von uns (i.e. Pictures of Us), a work about systematic abuse at a Catholic elite high school, describes from diverse perspectives how victims wrestle even decades later for the prerogative to interprets their own biographies.

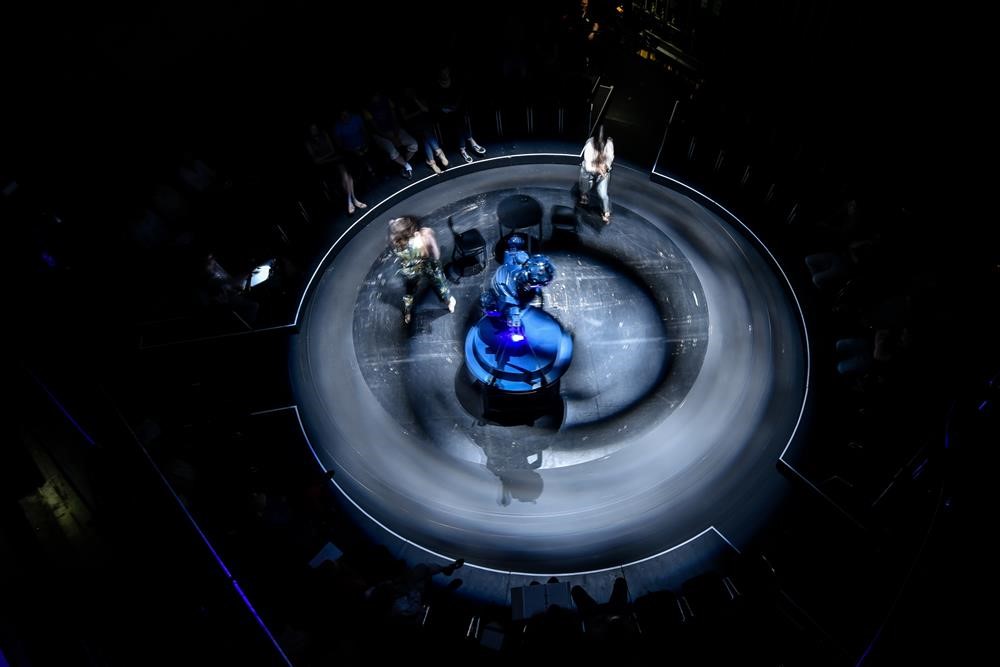

Constanze Becker, Till Weinheimer, Verena Bukal, Vincent Glander in Felicia Zeller’sZweite allgemeine Verunsicherung. Directed by Johanna Wehner. Photo credit Birgit Hupfeld

Looking beyond Mülheim to the other prestigious festivals of contemporary drama, the diversity of themes appears similar. The winning text of the German-language author’s prize at the 2016 Heidelberg Play Market, Maria Milisavljevic’s Beben (i.e. Quake), confronts real violence with virtual war games. In contrast, there are plays such as Stefan Hornbach’s Über meine Leiche (i.e. Over My Dead Body) and Sergej Gößner’s Mongos about individual experiences of crises. In the first text, a young man receives a cancer diagnosis, which becomes the starting-point of a process of self-questioning. In the second, a paraplegic and a teenager suffering from multiple sclerosis learn in a rehabilitation clinic to enjoy growing up even with physical limitations.

STANDARD CHARGE OF “NAVEL GAZING” PASSÉ

As with content, diversity is also the keyword with respect to style: more or less classical dialogue plays rub shoulders with epic approaches, developed plays with patches of text. The rule is confident hybrid forms consisting of all these writing styles. One point, however, applies to all the works presented from Mülheim to Heidelberg: the time when the new drama was reproached with the accusation of “navel-gazing,” of having too little to do with “the real world” and preferring to exhaust itself in the petty tragedies of relationships, seems to be over for good – if it ever really existed. Theatre authors now dare to take up, with admittedly varying degrees of literary quality, significant existential subjects. This may be seen in the texts that the jury of the 2016 Berlin Autorentheatertage (Theatre Authors Festival) chose for its premiere. Thus, for example, in Jakob Nolte’s Gespräch wegen der Kürbisse (i.e. Discussion about the Pumpkins) the small talk of two girlfriends slips into basic questions concerning missile launches and (drone) wars. And in Dominik Busch’s play Das Gelübde (i.e. The Vow) a young doctor in a crashing airplane vows that, if he survives, to work for the rest of his life in an infirmary in Africa – a pledge that meets in his affluent circle with blank incomprehension.

VARIOUS PERSPECTIVES ON AN EQUAL FOOTING

A common tendency in writing practice, also observable far beyond German-speaking countries, was given a name by the director of the Berlin Play Market, Christina Zintl, in her opening address in May 2016 at the Berlin Theatre Meeting. The recently multiply modified Play Market, which in 2016 sought by tender contributions from all over Europe on the “political dimension of narratives”, received more international entries than ever before. Four of the five texts or projects selected by the jury came from non-German-speaking countries. And although all the entries dealt with power structures, experiences of violence or war and crisis situations, what they had decisively in common lay beyond matters of content, to wit their productive “polyphony” and “brokenness of linear narrative,” as Zintl formulated it. Various perspectives co-exist on equal footing, a multiplicity of voices is the order of the day, diverse time levels flow into one another, as do reality and fiction. In short, diversity is writ large, no single angle lays claim to universality. This fruitful path of undermining supposed certainties and, to remain with the announced theme of the Berlin Play Market, rupturing established narrative structures was as evident in Mülheim and Heidelberg as in Berlin. So bright prospects have opened for contemporary drama festivals and play markets in the coming years!

Translation: Jonathan Uhlaner

This article was originally published on the Goethe-Institut. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christine Wahl.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.