Sociologist Max Weber once called politics “the slow boring of hard boards”. If he had been in the arts he might have added, “using your head as a drill”.

Australia’s cultural agenda often feels like an endless loop of intractable need. Adequate funding for the ABC. A commercially viable film industry. The right balance between metropolitan and regional funding. In theatre, a hardy perennial is the proposal for a National Theatre of Australia (NTA).

Last December, a forum was held at the Griffin Theatre in Sydney to discuss the issue. In response to what seemed generally negative views, I wrote a piece for Currency House calling attention to a national theatre’s potential social and artistic benefits.

The gist of my argument was this: let’s not imagine something we don’t want, then say we don’t want it; let’s see what needs improving and picture a company that can rise to the challenge.

A national theatre doesn’t have to look like the UK’s brutalist Royal National Theatre, or the wedding-cake edifices found across continental Europe. It doesn’t have to have a building at all. It can be an agenda, a programming resource that works through our existing organizations to extend what they are doing and better incentivize it, especially in the production of Australian drama.

The NTA proposal has been around for a long time. Calls for one were first heard shortly after Federation.

In the 1920s and 30s there were plans in Melbourne and Sydney for a national company that would, according to critic Leslie Rees, “reflect images of what it means to be human in our particular society”.

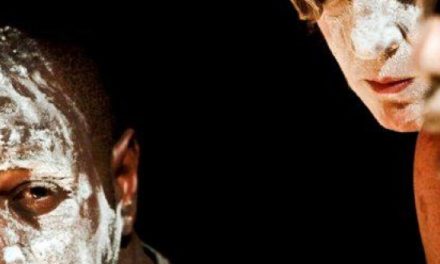

Martin Vaughan and Kate Mulvaney onstage at the Belvoir St Theatre in Kate Mulvaney’s The Seed, 2008. AAP Image/Tracey Nearmy

After the second world war, those plans seemed to be on the verge of becoming reality when the NTA proposal attracted the support of Prime Minister John Curtin and his economic adviser, L F Giblin. But then Curtin died unexpectedly and his successor, Ben Chifley, insisted on financial co-investment from state governments.

When this was not forthcoming, and when in 1949 the much-hyped Guthrie Report turned out to be a damp squib, hopes for a national theatre receded (though they never entirely disappeared – as the name of the National Theatre School in St. Kilda today testifies.)

In 1973, Gough Whitlam brought the arts into full Cabinet responsibility and doubled their budget. By this time Australia’s ad hoc collection of state theatres, pro-am companies, and residual commercial enterprises was fully entrenched.

Whitlam did not seek to reform the sector. He had enough on his plate, and besides, it is not necessarily the case that something planned is better than something which incrementally develops. A new type of company was appearing anyway, the Nimrod Theatre in Sydney and the Pram Factory in Melbourne, which suggested the future of Australian theatre was organisationally smaller and lighter on its feet. A grand enterprise promoting a uniform idea of Australian culture no longer seemed required.

In one very important way, this is truer now than ever. Australian theatre is more extensive, variegated, and complex than anyone 40 years ago could have foreseen. But this does not mean that the NTA proposal is outmoded, only that the type of national theatre the country requires today is different.

In my Platform Paper last year, The Retreat of Our National Drama, I identified the problems besetting Australian theatre because of its erratic development, what Peter Fitzpatrick aptly describes as “its history of beginnings”.

Two stand-out: the issue of promoting younger Australian playwrights into mainstream programming, and the issue of adequate revivals from the Australian canon. These are not the only problems the sector faces, nor the only ones a national theatre might redress. But they are among the most persistent.

The relationship between Australian theatre and Australian drama has always been uneasy and frequently dysfunctional. Examples are abundant: the conflict around Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Brumby Innes in the 1920s; the conflict around Patrick White’s Ham Funeral in the 1960s; the conflict around Alex Buzo’s Norm And Ahmed in the 1970s. The list is long.

Australian drama has historically been a contentious choice for Australian audiences, having to punch its way through to box office acceptance in a way that makes theatre companies, conscious of the bottom line, leery of taking the risk with it.

Wesley Enoch’s Black Diggers onstage at the Sydney Festival in 2014. AAP Image/Dean Lewins

In 2015 things are better but long-term trends are hard to buck.

The most important point to stress is that a national theatre, far from being a tool for producing a dull, monocular form of theatre, is a brilliant means of promoting diversity. It is a way of including the many sensibilities and talents that make up the cultural spectrum.

This is what the NTA proposal means today: not a vehicle for one-note nationalism, but vibrant engagement with the diversity of the nation by providing Australian artists with a common frame.

Being an advocate for a national theatre can feel like a job at once principled and doomed. Even those who support the idea don’t think you stand a chance. Better to concentrate on what’s achievable. Which means, in practice, what’s affordable. Which means, waiting for politicians to decide what spin to put on Australia’s prospects this week.

Since our current government only has one economic idea–to cut public expenditure–this makes a national theatre’s prospects close to Buckley’s. It’s a bad time to engage in blue skies thinking, I am told.

But the opposite is true. Not only for strategic reasons – because a national theatre is a useful corrective to a theatre sector that has evolved haphazardly, with gaps in significant areas of activity – but as a way of combating the moral dwarfism of our time, its shallowness and fragmenting self-regard, the NTA proposal is an important one to debate.

It is a way of reminding ourselves that Australian theatre, and the country at large, is more than a collection of market segments and end-users, a convenient organizational arrangement we cannot question because it is obviously the right one.

Australian theatre and the country at large is what we decide it will be, a social imaginary. We can choose to support a national theatre, just as we can choose to support any institution that expands what the philosopher and writer Charles Taylor calls “the repertory of collective actions at the disposal of a given sector of society”.

There are always choices to be made. If we don’t take the initiative, history makes them on our behalf, and they will seem “inevitable” when they are nothing of the kind. Australian theatre is a thriving sector, and its cultural and economic contribution to the nation is substantial.

A national theatre would be a way both of recognizing that contribution and increasing it.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on February 17, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Julian Meyrick.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.