Baba Brinkman’s Rap Guides in Repertory This Fall

For starters, you might be skeptical that a 40ish white Canadian guy can rap. You might also be skeptical that rap can convey complex scientific information without losing its groove. And you might even be skeptical—should the first two doubts be defeated—that you’ll gain any real theatrical benefit from the combination of beats and brains. Lay all that aside—I did, and I got quite a buzz at Baba Brinkman’s Rap Guide to Consciousness, playing at New York’s SoHo Playhouse in repertory with a handful of Brinkman’s noted and notable and award-winning shows: Rap Guide to Religion; to Evolution; to Climate Chaos; to Culture. The most recent is the latter which is direct from its World Premiere at Edinburgh Fringe. It takes an evolutionary approach to culture, so, if you’ve wondered what science can tell us about art, it’s the one you need to see.

I caught the Consciousness show because—mainly—it happened to occupy the best slot for my attendance, but also because it’s the one that made me most curious. I felt that almost anyone worthy of the name “rap star” could rap about culture or about hot-button topics like climate change, while religion and evolution—those polestars of creationist and scientist debate—however fun as opposing views sound to me pretty familiar. But consciousness? It’s a nebulous topic, even if you come at it, as Brinkman does, from neuroscience more so than Greek or Indian philosophy. It seemed to me that Brinkman was throwing down a pretty big gauntlet for himself. What’s more, without some idea of how the circuitry in our skulls works, all those other topics are just window-dressing to the big questions: Who says? And how do you know?

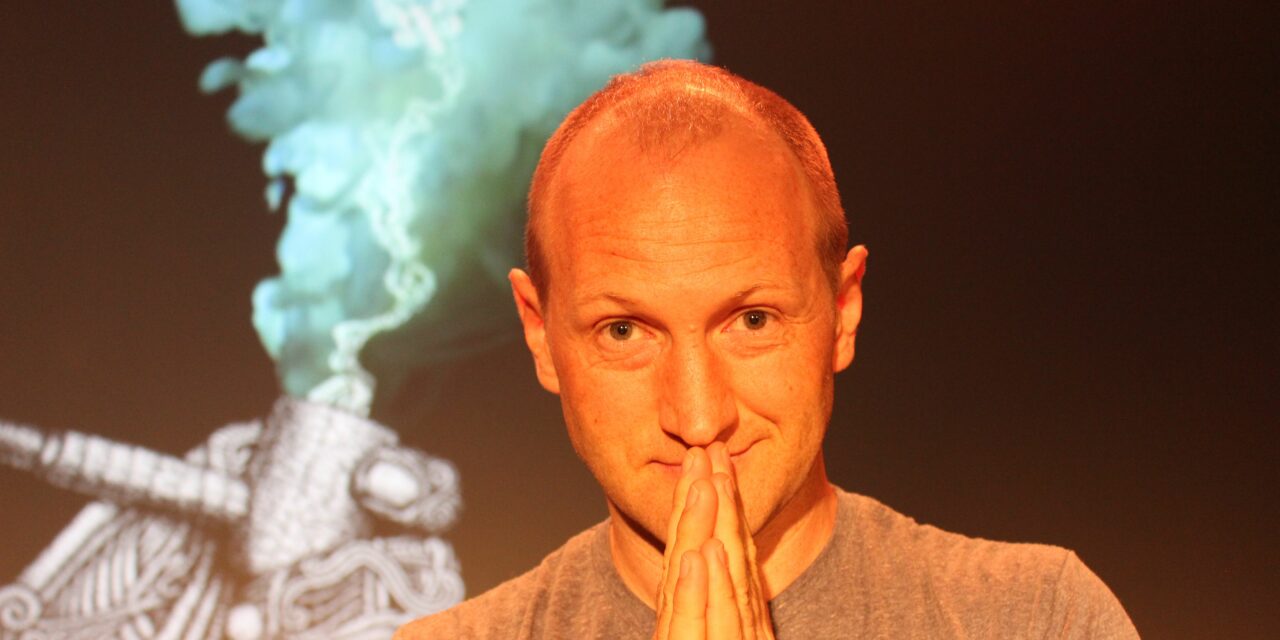

Baba Brinkman in Rap Guides. Photo by Dawn Brinkman.

I didn’t know, going in, that Brinkman’s wife is a neuroscientist and that he already had amassed a considerable rep as the purveyor of the first-ever “peer-reviewed rap.” In other words, he’s not some zine-based zany proclaiming the world as he sees it. At the end of the show, he even leaves up a screenshot of books that comprise his bibliography. Which could make this sound like some would-be prof on his day off trying to keep it real and play it hip. Dude even has an MA in Comp Lit—I’ve got a Ph.D. in same so I might not be the best person to judge if this show is street enough for y’all. But by my lights, Brinkman is humble enough in his demeanor and cocky enough in his skills—he addresses all the above doubts and more as topical asides—to bring it off. He even brings up his wife as a reference point by saying he had to get up to speed in knowledge about the brain just to get a date. As a standup, Brinkman’s Guides make their own rules.

Which is to say that one way Brinkman keeps Rap Guide to Consciousness from being an abstract class, with tempo, on the brain’s most famous illusions, paradoxes, and confusions, is to make it autobiographical and not just biological. We learn that he earned the nickname Baba because his dad thought infant Brinkman had the eyes of a wise seer—like Meher Baba, perhaps (and maybe he knew his kid would get his back into his living). And that Brinkman’s own male progeny is named Dylan, and we get a video of arguably pre-conscious Dylan goo-gooing while Brinkman raps about the likely state of our newborn brains. There’s even an emphatic aside about how much the visuals of a certain Google program simulate the viewpoint of someone tripping. Now, how would he know that?

Baba Brinkman in Rap Guides. Photo by Dawn Brinkman.

It figures, though, because Brinkman’s rap is itself a trip, full of flights and jabs, jokes and apt rhymes, asking us to weigh in on questions that help to fuel arguments about how we manage to make sense of a world our brains are only approximating. Though, going in, I couldn’t have said much about such topics as “Fame in the Brain” and never heard of English philosopher and mathematician Thomas Bayes, I did have some vague idea about many gray areas in gray matter research, and it is fascinating, enlightening, and entertaining to hear Brinkman rap them into our consciousness. At times—for oldsters like me—the syncopation can get a bit wearying, but Brinkman keeps the flow moving in varied rhythmic streams (music by Tom Caruana and Dan Moross), some of them very catchy. And as a performer, Brinkman, directed by Darren Lee Cole, has good moves and great rapport.

The screen of rapid-fire visuals behind him—via Olivia Sebesky—runs seamlessly as if wired to his every gesture, and his interactions with the audience add a nervy spontaneity. He takes topics or questions or suggestions and works them into the material—and while we might expect that to be de rigueur for any boss rapper, here it’s part of the argument about free will. That topic is one of those thorny consciousness concerns—and, judging by the history of philosophy, it seems no one is ever satisfied with someone else’s solution. Brinkman, steeped in the best science can make of the question at present, seems to hold out for both the mind’s unpredictable imaginative freedoms and for the mind’s ability to model—better and better—how that freedom works. But if it’s work, is it free?

Baba Brinkman in Rap Guides. Photo by Dawn Brinkman.

I’m sorry that I could only take in one of Brinkman’s shows, on this go-round anyway, but I urge you, if you’re in the neighborhood of Manhattan, to look up at least one of them (or check out the three-show package). I suspect you’ll find (because you’re probably way more into hip hop, computer graphics, and interactive phones than I am) that Brinkman speaks your language and that he can make the kinds of concerns that exercise our minds—including our minds themselves—into fast-paced, educational, fun, and deeply human theater. As in: full of concern for the things that humans are faced with solving—like how we got here and what our relationship to the planet and its other inhabitants should be. And how we even know the stuff we think we know.

Brinkman knows he’s playing with us—much as any comedian, monologist, or college professor does—to keep us in his script. And I’ve noticed a tendency in theatre these days to be rather declamatory, with characters standing on the stage to address some “you” who may or may not be in the theater. That’s a given for Brinkman’s Guides. The question of who “we” are might be more germane to the other shows on his docket—like, whether or not his listeners believe in God, evolution, accept climate change and get references to Jennifer Anniston. Maybe yes, maybe no, but we can assume that anyone listening at Consciousness has a brain and—even if they turn their phones off—are able to be there and somewhere else, mentally, at the same time. The struggle is to keep our minds on our minds, and Brinkman succeeds in making a show that shows what we know and don’t know, and why that matters to minds like ours.

Baba Brinkman in Rap Guides. Photo by Dawn Brinkman.

Baba Brinkman’s Rap Guide to Consciousness

Written and performed by Baba Brinkman

Directed by Darren Lee Cole

Visual Design by Olivia Sebesky

Music by Tom Caruana and Dan Moross

In repertory with Rap Guide to Culture, Rap Guide to Evolution, Rap Guide to Religion, Rap Guide to Climate Chaos

SoHo Playhouse

15 Vandam Street

New York, NY 10013

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Donald Brown.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.