I am going to be honest. I didn’t see Verdi’s Rigoletto at the Real. I had wanted and planned to go but, in the end, circumstances conspired against me. The opportunity to watch the recording broadcast across cinemas in Spain on 20 December allowed me to catch up with the work of a director whose work I much admire. Miguel del Arco’s lean aesthetic and ability to reimagine classic texts in an inventive and highly relevant manner has proved hugely influential. In La función por hacer/The play to be played also translated as The play to be done, which first premiered in 2009, he presented a brisk, timely re-imagining of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, linked to Spain’s economic predicament. In La violación de Lucrecia/The Rape of Lucrecia (2010) – he denounced the normalisation of a culture of abuse with a stellar Nuria Espert inventively taking on every role. Jauría (2019), a verbatim realisation of the trial of la manada for rape, confirmed a commitment to deconstructing the misogyny that too often passes for “normal” in Spain. This new staging of Rigoletto, a coproduction with ABAO Bilbao Ópera and Seville’s Teatro de la Maestranza, is a further example of del Arco’s commitment to theatre as a way of engaging with what artistic works mean in the here and now of the moment of staging, works where he exposes the noxious culture of machista entitlement that still underpins society.

This is a resolutely contemporary setting where the predatory nature of entitlement and female abuse is all too visible. The overture opens with a woman being pursued onstage, running for her life. Women are hunted in this rapacious world – fodder for amusement and entertainment by men that see them as disposable entities for their pleasure. Javier Camarena’s smug Duke of Mantua is attired in a brilliant white suit, centre stage as he commands attention and obedience, chasing Ceprano’s wife and presiding over a culture of debauchery and hedonism – surrounded by a harem of writhing dancers in gold lame from which Count Monterone’s daughter – the woman chased through the auditorium by the masked courtiers – unexpectedly emerges.

Del Arco provides an effectively lean transition from the court to Rigoletto’s house — avoiding an unnecessary scene change as the Count’s jester removes his headdress and bodice and puts on a black one armed suit, ironically emphasising his Joker credentials. Sparafucile (Peixin Chen) is an impressive, fittingly menacing assassin: dark glasses, trilby, cane and knuckle dusters, leaning over Ludovic Tézier’s Rigoletto — the latter haunted by Monterone’s curse for mocking the violation of this daughter by the Duke.

Gilda’s first reveal demonstrates del Arco’s slick stagecraft, cocooned in a bubble of greenery, isolated from the Court, and later on, after the departure of her father, flummoxed by the Duke’s intrusive appearance in the family space of safety. Later in the final act, Marina Viotti’s Madalena in her distinctive platformed white boots towers over her brother and the Duke, answering them back with defiance and verve, determined not to become a sexual plaything.

Sven Jonke – a founding member of the Croatian-Austrian design collective Numen/For Use — and Ivana Jonke, both here working with del Arco for the first time — renders a non-realist set of floating, undulating drapes. There are red curtains falling dramatically to the floor at the beginning of Act 3; they rise to create a tent-like structure of Sparafucile’s bar where sex workers shake and sway like drunken zombies as the Duke drunkenly sings the famous “La donna immobile” aria around clusters of colourful plastic outdoor furniture. The fabric mounds create a mountainous backdrop for Rigoletto’s Act 3 discovery of Gilda’s mortally wounded body, masking the culprits while exposing his pain and incredulity. Rigoletto appears a tiny figure, exposed in the open landscape as the drapes flap wildly in the distance. This is a set at once abstract and mysterious, where nothing is quite what is first seems.

Juan Gómez-Cornejo’s lighting design creates pockets of action. Large unforgiving chandelier-like lights burn down on the Court in Act 1, exposing the poor behaviour of the Duke and his courtiers. At the end of Act 1, the masked courtiers emerge from the darkness, their white bunny masks ominously brightening the stage as they kidnap Adela Zaharia’s Gilda. Naked dancers appear – perhaps angels – to accompany the now dead Gilda as she stands motionless behind her grieving father at the opera’s end. Gilda continues to exert a powerful presence over her father in death as much as in life. Ana Garay’s costumes are brash and fittingly ostentatious.

Nicola Luisotti conducts briskly — some may say too briskly – setting up the pace for a fast and furious production. Censored during Verdi’s lifetime, rattling the authorities in its depiction of privileged aristocratic excess, del Arco finds a brash unromanticised tone for his resolutely contemporary staging. Powerful men that do not see responsibility and accountability as necessary are brutally exposed. They may not see the errors of their ways, but del Arco’s production makes it brutally clear that the audience need to. The staging makes for uncomfortable viewing: abrasive, in-yer-face and provocative. It has certainly split audiences — who may have expected more sanitised Christmas entertainment from the Real for the holiday season. And while it may not reach the dizzying heights of Jonathan Miller’s superb New York Little Italy-set production for English National Opera, it demonstrates the brittle edge of an opera that continues to unsettle in its depiction of toxic masculinity and impunity. In an age where powerful predatory men like Jacob Epstein and Donald Trump leave a wake of destruction behind them, this Rigoletto feels particularly timely.

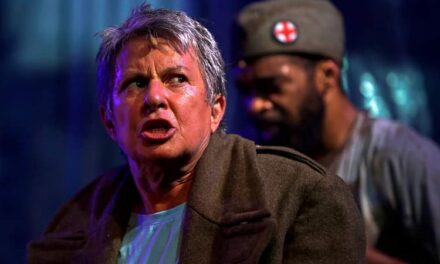

A grief-stricken Rigoletto (Ludovic Tézier) and the dying Gilda (Adela Zaharia). Photo: Javier del Real, courtesy of the Teatro Real, Madrid

Rigoletto played at the Teatro Real Madrid from 2 December 2023 to 2 January 2024. Future performances in Bilbao and Seville during 2024.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.