In June 2019, Columbia University School of Arts staged the second annual International Play Reading Festival, presenting plays in English translation from Spain, Chile and France alongside discussions on theatre translation and internationalization of Anglophone stages. Here, John Brunner reflects on the events of an eclectic three days of world theatre.

There’s something about a conversation had over wine, cheese, and French bread that you’ll never forget. I fully believe the French, post-dinner ritual of a fromage plate needs to cross the Atlantic. Some of my most vivid memories of living with a host family in Tours, France are these post-dinner conversations. Politics, arts, current events, sports- no topic was off limits. During one of my first few conversations with my host family, when I was still simply trying to parse together anything meaningful in this new language, the topic of my home university came up. “Dix-sept heures” I said. My host sister’s jaw dropped. “17 hours” was my reply when she asked me how far I lived between home and my university in Pennsylvania. To my host siblings, this distance was insane. “That’s the time it would take to get to Russia!” my host brother replied. “Oui,” I confirmed, “the United States is a big place.”

I found myself recalling this conversation as David Henry Hwang, the celebrated playwright and the chair of the MFA Playwriting program at the Columbia University School of the Arts, welcomed the audience to Columbia’s Second International Play Reading Festival. Presented June 14th through the 16th at Columbia’s Lenfest Center for the Arts in New York City, the festival featured three play readings, a panel discussion on theatrical translation, and a moderated talk with festival’s playwrights. Hwang, in coordination with Dean of the School of the Arts Carol Becker, organized the festival and a five-person selection committee determined the three plays selected for presentation.

Featuring works from France, Spain, and Chile, Hwang explained the mission behind this weekend was to help continue to establish Columbia University as an international art institution. As he rightly pointed out, American theatergoers are rarely exposed to non-domestic works, save maybe those from other English speaking countries such as the United Kingdom or Ireland. There are only a few nations on Earth where you can drive 17 hours without leaving the country. With substantial diversity found in all corners of the United States, we could easily focus on only our own artists. Hwang hopes, however, the festival will be a step forward in correcting an often myopic American theatre scene.

On Friday night, the festival began with the French play Snow by Blandine Savetier and Waddah Saab, translated by Taylor Gaines, and directed also by Savetier. A stage adaptation of Nobel Prize Laureate Orhan Pamuk’s novel of the same name, the play centers around the people of Kars, Turkey as they struggle with the political suicides of young Muslim women. Ka has returned home to Kars from Germany to report on these deaths and to reconnect with a past love. A respected poet and journalist, Ka finds himself largely unprepared for the political, social, and religious debate he has waded into.

On the precipice of consequential elections, Kars stands torn between balancing a secular society with its religious values. As violent extremists begin to terrorize the city, everyone’s future seems uncertain. Despite dealing with heavy issues, Savetier and Saab appropriately balanced the serious with the humorous while also ensuring their many characters felt human. Interweaving debates over the separation of church and state and secularism versus religious freedom, Snow may take place on the other side of the globe but its dramatic themes will feel very close to home for American audiences.

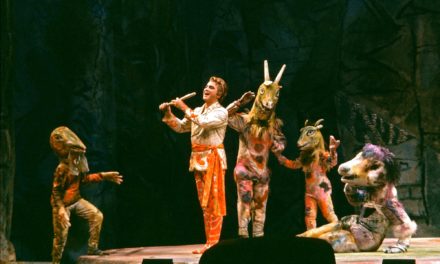

The Sickness of Stone by Blanca Doménech, translated by William Gregory, directed by Nana Dakin. Photo (c) Michael DiVito

The festival’s second reading dove deep into the complexities of historical preservation with Blanca Doménech’s The Sickness of Stone, translated from Spanish by William Gregory and directed by Nana Dakin. Set in Spain’s Valle de los Caídos, or the Valley of the Fallen, this play portrays the ethical and societal complexities of historical restoration. During this reading, I was reminded of my almost visceral response, several weeks ago, to witnessing a sizable portion of the Cathedral of Notre Dame burn to the ground. In the hours and days after the fire, millions of people were reminded of the importance of preserving our past, and the cultural cost when we fail to do so.

The play’s characters, Miranda and Andres, find themselves trapped inside the monument as a conflict between two political groups, including Neo-Nazi’s, erupts in gunfire outside. Despite this monument being an imposing yet magnificent piece of architecture, it is also the burial site of the fascist dictator Francisco Franco who ruled Spain for nearly 40 years. Doménech uses her play to explore the ongoing debate of grappling with a nation’s difficult past. Miranda, a young yet talented architect trained in historical restoration, has fought to remain neutral on the morality of this historical site. Nevertheless, the conflict outside its doors forces her to take a side. At the same time, the audience must consider its own nation’s responsibility towards the darker parts of its own history.

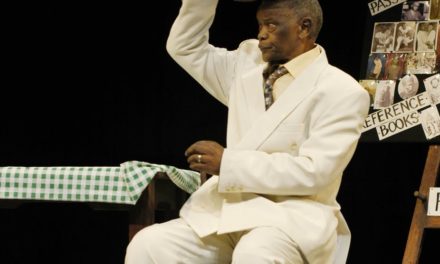

You Shall Love by Pablo Manzi, translated by Cristóbal Pizarro, directed by Ellie Heyman. Photo (c) Michael DiVito

Finally, Chilean playwright Pablo Manzi’s You Shall Love, directed by Ellie Heyman, concluded the festival with a witty yet urgent conversation on “otherness.” Translated from Spanish by Cristóbal Pizarro, the play centers around the arrival of aliens, known as Amenites, on planet Earth. They have come to our planet not as invaders, however, but as refugees. Set in the near future in a contentious medical boardroom, the play focuses on a group of doctors struggling with how to care for these extraterrestrials despite their cultural, societal, and biological differences. The doctor’s own beliefs and biases are tested, especially when a member of their own group turns out not to be who he said he was. Furthermore, You Shall Love challenges the art of medicine as an act of humanity. An argument for everyone’s need to be treated with respect and dignity, Manzi humorously and compassionately handles the question of what to do when “others” show up, in need, on our own doorstep.

Overall, in addition to celebrating the playwrights, it was exciting the festival highlighted the important and complex role of the translators. Often overlooked and underappreciated, their work is much more than just adapting a play into a new language. Translators pursue to make different cultures accessible to an audience while also honoring and respecting the playwright’s voice. Additionally, they must account for gaps in an audience’s knowledge, translating another culture’s norms, values, and even current events.

Susan Bernofsky, Caridad Svich, and Taylor Gaines discuss ‘How Did This Play Get into English?’ Photo (c) Michael DiVito

During Sunday’s panel discussion entitled “How Did This Play Get Into English?,” Gaines discussed the importance of cultural translation during her work on Snow. To begin, she pointed out her work is based on her interpretation of Savetier’s and Saab’s play Neige, a theatrical adaptation of a French translation of the Pamuk novel originally written in Turkish. Did you follow that? Now layer in the complexities of both the French and Turkish debates over the Muslim tradition of women covering their heads with a scarf, or hijab. And the aforementioned debate of societal secularism versus religious freedom. Oh, and the clash of western versus eastern cultures. Still with me? Translators are artists in their own right and they work needs to be continually celebrated.

By showcasing three very diverse and thought-provoking works, Columbia’s Second International Play Reading Festival strongly demonstrated the university’s commitment to providing a New York stage for international artists. Furthermore, it provided audiences with free access to new and established playwrights whose voices are valuable and needed in the United States. Yes, our country is a big place and you’ll find a diversity of perspectives if you drive from coast-to-coast. But a festival like this helps remind us not of the differences with artists from say France, Spain, and Chile, but also of the shared similarities of our human experiences.

John Brunner, an Arkansas native, is a New York-based director and dramaturg. He is currently a candidate for an MFA in Dramaturgy at the Columbia University School of the Arts.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Brunner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.