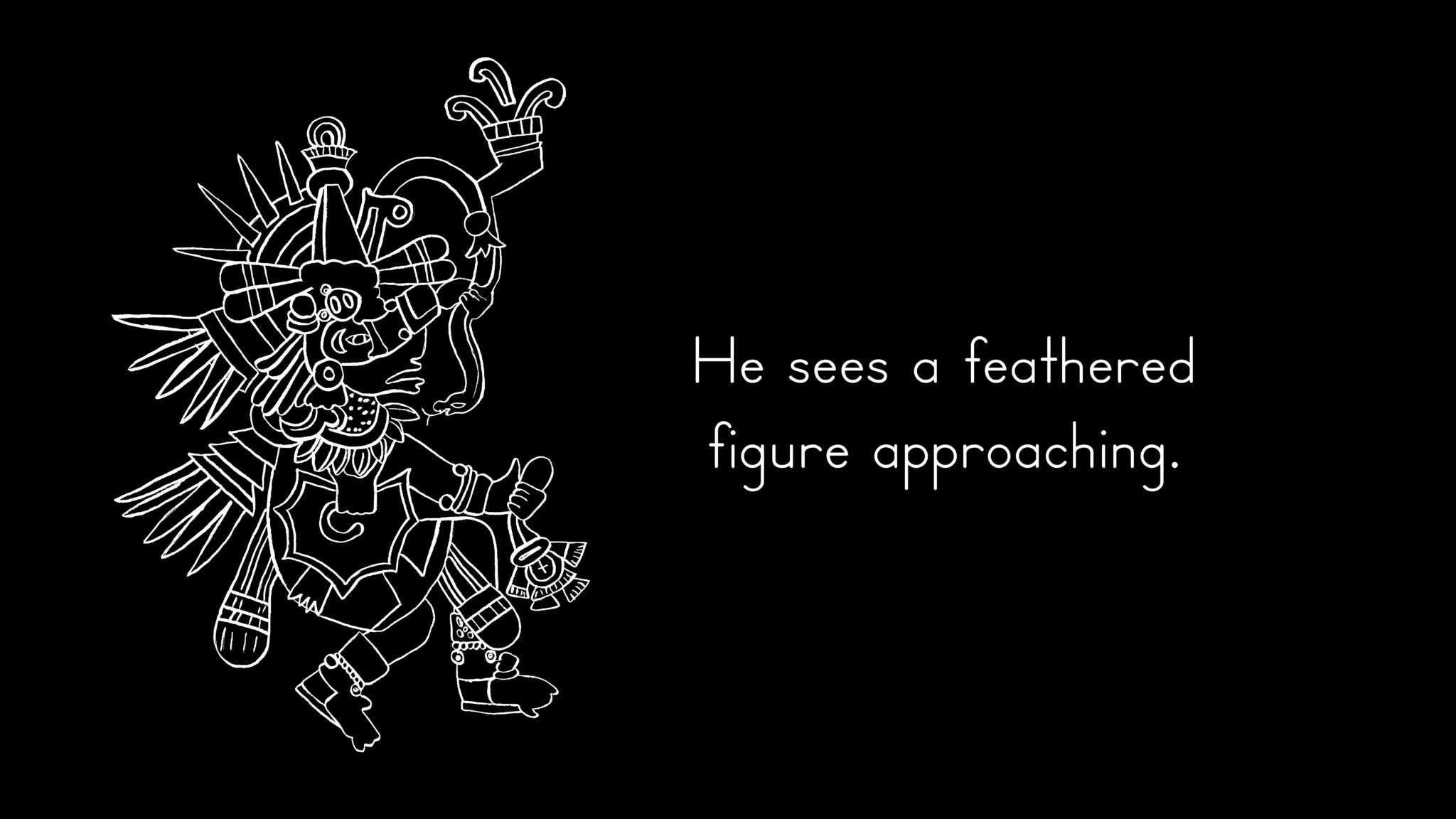

In advance of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s forthcoming exhibition, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage (July 30, 2017 – January 7, 2018) LACMA premiered Frances Stark’s rendering of the Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s score / Emanuel Schikaneder’s libretto of The Magic Flute (2017). The approximately 110-minute animated film adaptation in two acts of the popular 1791 opera is about a prince and a bird catcher who cross paths and endure various tricks and trials in search of love. Stark, who is represented by Marc Foxx Gallery in Los Angeles, will take the film to the biannual events at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and then on to Venice.

In her introduction of the film before an SRO crowd, Stark made note of the fact that the piece was Mozart’s last one; he died 5 weeks afterwards at the age of 35, and, thus, for her, this premiere gave her pause. She seemed quite relieved and happy with the outcome. For the past 25 years, Stark’s unusual approach to lyricism and her signature economy of means are employed in full force in the film: “I’m trying to make The Magic Flute unfold for people very directly and joyously; it isn’t about clever redressing or anything, it’s really about the bare bones of the opera having the capacity to engage you, the original accessibility of the opera was based on its high-low conceit.” The Overture is played in its original form and recorded with a full orchestra. The remainder of the opera is more experimental and was recorded in smaller studio sessions with a full string section and solo wind and brass instruments assigned to play the vocal melodies.

While I love friends who love opera, I am not a natural opera lover for many of the same reasons I don’t read long novels. I am happy to report that Stark has created a novel way to guide the listener through the narrative without the distractions that come from stiffly staged performers, no matter how splendid the production designs. According to one press hand out: “Stark’s adaptation of The Magic Flute confronts notions of power, cultural capital, and institutions (i.e. the museum, the university, the opera) with an invitation to a more humanized experience of beauty, kinship, and art.”

According to one press release, “The audience is invited to experience the work as a ‘pedagogical opera.’ In other words, an opera that is closely read and/or taught. This artistic impulse reflects past breakthroughs in Stark’s work which have consistently reflected her attempts ‘to understand and manifest an erotics of pedagogy capable of voicing my poetics and challenging the art audience while also engaging youth.’”

Let me unpack the experience in simpler terms. I agree that “the presentation demanded close viewing, a lot of reading, and listening.”

There are no vocal parts. Rather, vocalists have been substituted with instrumental soloists (local performers ages 10 – 19!) who play the respective character’s melodies. In the opening titles, the young musicians are shown lined up across the screen with their instruments in hand; text equates the instruments with the characters a la Peter and the Wolf. The overture was recorded with a full symphony orchestra; the balance of the score is performed by a 13-person string plus timpani section.

Super titles take center stage. There is no attempt to design a production with sets, costumes, props, lighting, etc. It’s a visual desert, but that makes way for Stark to accomplish what she set out to do (see aforementioned paragraph). In addition to the instrumental soloist, each “character’s” libretto, adapted by Stark into English, is set in distinct fonts and colors that are pulsed to keeps pace with the music. This does not overwhelm the listener with a) language that one doesn’t understand and b) the seemingly endless repetition of phrases. For example, in the case of the three female spirits who come upon the protagonist Tamino in the opening act, their individual lines are represented by one of three tones of violet cursive style font. When they sing as a trio, three lines are seen on the screen. Nothing else. Call – response phrases among characters are more likely included in a single frame than presented via a lot of switching. Thus, the editing is key to keeping pace with the score. While I found the approach helpful, as it provided a synopsis of what was transpiring in the narrative, the conceit became boring after a while.

Visually sparse. Familiar images reminiscent of Stark’s graphic vocabulary enjoyed in the mid-career exhibition (see below) often prompted scene breaks, and unfortunately, more often than not, the screen was blank. One press release advised, “Her unique balance of light-hearted jest and philosophical inquiry ventures into the bawdy while remaining elegant, often probing prickly issues of race, class, and gender with joyous and agonizing sincerity.”

Lyrically accessible to a contemporary audience unschooled in the pomp and circumstance of grand opera. The lyrics have also been updated through Stark’s creation of an “amalgam libretto” derived from the study of numerous translations.

Collaborators. For the project Stark collaborated with a set of artists from disparate parts of the music world. Conductor Danko Drusko, a PhD student at the time of the production, adapted the entirety of Mozart’s score. He also oversaw each rehearsal and conducted the players during each recording session. The legendary producer and arranger H.B. Barnum recorded and mixed the music; cellist and mezzo-soprano instructor Ameena Maria Khawaja organized the audition and the student players throughout the entire process; and percussionist and film composer Greg Ellis added rhythmic effects and finalized the soundtrack.

Stark has collaborated with a writers, dropouts, virtual partners in online video platforms. More recently, she worked with Bobby Jesus on the video installation Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater B/W Reading the Book of David And/Or Paying Attention is Free (2015). Her recent works demonstrate novel ways of storytelling, with sexual overtones, poetic verve, and comic timing. My Best Thing (2011). She began working on The Magic Flute following the opening of her critically praised mid-career survey UH-OH: Frances Stark 1991–2015 (2015–16) at UCLA’s Hammer Museum – which I truly loved — and receiving the 2015 Absolut Art Award. It was also developed in the wake of a highly publicized withdrawal of the entire class of MFA students at USC’s Roski School of Art and Design amid administrative changes. While she had resigned from her position several months prior, she felt that the university “flaunted an egregious disregard for the fundamental human endeavor we cherish as Art. She remarked, “I believe what is at stake here is not confined to the academy but involves the entire fractured cultural landscape of Los Angeles, the fragile role of the individual artist, and the un-commodifiable human voice itself.”

I think Stark is on to something that can build audiences from the next generation of opera lovers.

Stay Tuned for LACMA’s Presentation of Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage!

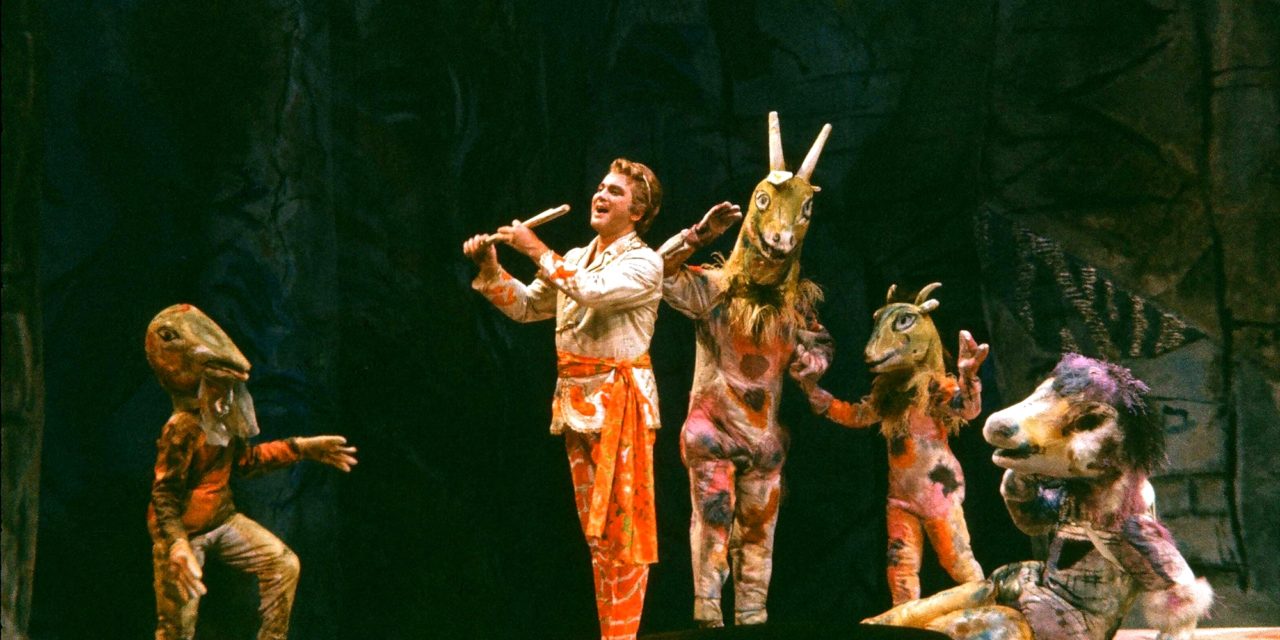

Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage communicates the moving and celebratory power of music and art, and spotlights this important aspect of the artist’s career by the presentation of his vibrant costumes and set designs—some of which have never been exhibited before. In addition to his pieces for The Magic Flute (1967), the exhibition will include works from the ballets Aleko by Tchaikovsky (1942), The Firebird by Stravinsky (1945), Daphnis and Chloé by Ravel (1958). In addition, the exhibition features a selection of iconic paintings depicting musicians and lyrical scenes, numerous sketches of his theatrical productions, and documentary footage of original performances.

According to Stephanie Barron, LACMA’s senior curator and department head of Modern Art, music and dance played in Marc Chagall’s artistic practice, which is deeply linked to his Russian birthplace and upbringing. A significant source of inspiration and a central theme throughout his extensive oeuvre, music permeated Chagall’s engagement with modernism, from his early canvases in the 1910s to his first creations for the stage in the 1920s and his monumental set designs of the 1940s–1960s.

The exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts where it will be on display, January 24–June 11, 2017, and was initiated by the Philharmonie de Paris – Musée de la musique, and La Piscine – Musée d’art et d’industrie André Diligent, Roubaix, with the support of the Chagall estate.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren W. Deutsch.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.