Two productions, both under musical direction of Valery Gergiev, were put on at Mariinsky Theatre on consecutive days in February 2020: Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Rodion Shchedrin’s Lolita. Both are new productions for the Mariinsky Theatre: Anna Matison’s original staging of Debussy’s masterpiece opened in October 2019 and is still in its extended premiere season, while Slava Daubnerova’s production is a transferal from National Theatre in Prague (2019) with the same Russian soloists. Both operas explore erotic and love longings that lead to disasters, but the material is radically different. The first is a tragedy of the mythological, symbolical kind, and the second explores the individual’s journey into unknown lands of erotic wishes that are banned by society. The differences between mark the huge watershed that lies between the 19th century when fairytales, romanticism and deep connection between human souls was still possible and the following centuries of self-centered individualism and self-probing encumbered by subdued and unexpectedly exploding libidos. It is striking how different the after-taste is: the catarthic, fresh and empowering Debussy compared with the tension, shock, exhaustion and pain after Shchedrin’s new opera. Both lead the audiences to better understanding of the extremes to where human soul and body can go.

Part One. Pelléas et Mélisande by Claude Debussy (conductor: Valery Gergiev, director Anna Matison, premiere on 24 October 2019 and through the 2019/2020 season).

Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande is the only opera of the French composer, and it received its premiere in 1902 at Opera Comique in Paris, conducted by André Messager. It is based on the play by Belgain playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. The story line follows the doomed lovers Paolo and Francesca, a love triangle involving the husband (older brother) and finally, their deaths. Debussy saw the play in May 1893, abandoned his another project and set on the path of writing music for it. He understood the piece not as an exotic rendering of a Middle ages love and jealousy story, but something introducing new aesthetics into the world of theatre and – possibly – music. This material allowed Debussy to explore formerly unknown possibilities in orchestral and operatic writing, breaking away from Wagnerian tradition that influenced him a decade earlier. Pelléas et Mélisande still remains an important milestone in the opera history because of the new way human speech and thought is rendered in its music, the subtle, almost eery orchestral writing, and the links between sounds and the viewer’s own imagination.

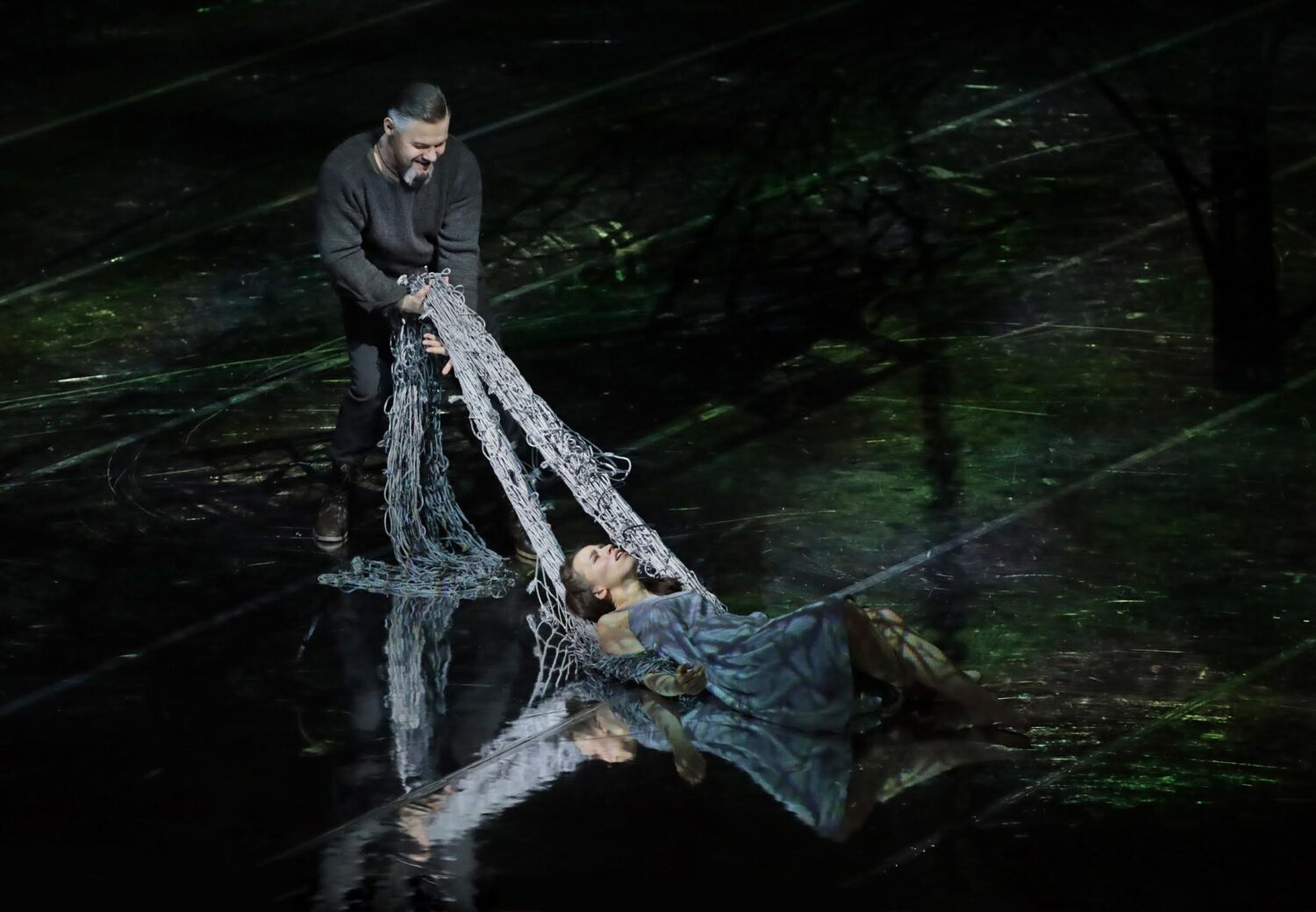

Anna Matison, director, costume, and set designer (the latter being a collaborative work with Marcel Kalmagambetov), has sensed the presence of mysterious levity in this opera incredibly well. Together with her team, lighting designer Alexander Sivaev, choreographer Sergey Zemlyansky and video graphics designer Alexander Kravchenko, she masterfully succeeds in transforming the Mariinsky Concert Hall into a transcendent place that doesn’t belong to any time or place and where the unknown laws of existence have their unavoidable impact on fragile human lives. Paradoxically, it is easier to create this intimate globe of nothingness in the Concert Hall that is surrounded by viewers on the side and in the choir than at the main Mariinsky stage. A huge frame of an old ship is hanging above the stage, and when Golaud arrives with his new wife, the frame slowly finds its way to the ground and remains till the end, with its narrow stem striking high towards the sky – almost like a human soul rooted to earth.

Pelléas et Mélisande Photo by Natasha Razina.

This ship frame is anchored by little globes emmeshed in fishing nets – they are so beautiful that it begins to look like a little castle itself, an entity of mystery, memory, past and future. These same little globes that look like game balls are the ones that will unite Pelléas and Mélisande during the opera: they throw it to each other like children when they meet, they have it at their walks and one magically bursts flowers when they confess their love. Matison uses the ship multifunctionally, as Golaud’s bed opens up as part of its stucture. The well where the wedding ring will disappear is on the left, the fountain of water strikes occasionally from the ship’s figurehead representing a maid allowing a pigeon to fly. The dining table on the right with high-backed chairs surrounding it is another piece of opera’s decoration. While always being shaded in semi-darkeness, a relatively small Concert Hall stage still looks magnificently spatious and mysterious, with the sea, forests, beach and underground passage easily imaginable. A group of dancers/actors helps to create the opera’s unique atmosphere – they are dressed as Greek Moirai, their mouths covered by red ribbons and their heads and bodies engulfed in white clothes. Appearing with a big piece of material spread between them, they introduce the symbolic meaning into a particular scene (red for jealousy and fear, blue for fate or love perhaps). In the end they reflect Golaud’s guilt with grins through a huge mirror they hold, while also marking the pace of death with beats of forks over the table.

Pelléas et Mélisande. Photo by Natasha Razina.

Anna Matison introduces the mysterious Mélisande (Aigul Khismatullina) by a very interesting decision: the heroine appears with a knife and a cut braid in her hand, and drops a ring she holds into the well. In the end, her long braid is again being cut off by Golaud, she wakes up, takes his knife and her braid, and murmurs something indicating she doesn’t know where she is, and will drop the ring that Golaud put back on her finger, into a well again. She is das ewig weibliche, the eternal woman and source of love dying and resurrecting without reason – an interesting interpretation by the opera director. Matison empowers Mélisande with deliberate choices – she doesn’t lose Golaud’s ring in the second act, but forcefully abandons it, and she cares for Golaud out of obedience, while opening up to Arkel. Golaud (Andrey Serov) is a deeply-tormented, multi-dimensional character who passionately loves his wife and goes through the hell of jealousy and guilt followed by attempts at forgiveness and tenderness towards his son, brother and wife. Ynold in the production is played by a wonderful boy, Alexander Palekhov, who conveys a child’s naivetés mixed with adult sensitivity. When he first appears, he draws a line of fuming irons along, imagining they are his ship armada bringing to mind the symbol of this production – the existence of weights that keep human souls to the ground, while the liberty of sky (and death) is so near. Pelléas (Gamid Abdulov) is probably the least mysterious character – a youth suddenly getting too serious in his explorations. The king Arkel (Oleg Sychev) is very eloquent in his singing, while always physically tied down to the chair. He suddenly loses his blindfold towards the end, and, while holding a new-born baby in his hands, allows us to glimpse a tangible tie between life and death in this opera that is indeed an endeavous to explore things not-seen and unimaginable. This production powerfully reawakens our imaginations, and the tragedy of its characters’ death almost feels like a relief, or resolution, as we, together with them, can for a brief moment enter the void hovering above us, leaving the weights of little globes anchoring us to life, behind.

Part Two. Lolita by Rodion Shchedrin (conductor – Valery Gergiev, director – Slava Daubnerova) Premiere at Mariinsky Theatre – 13 February 2020.

Rodion Shchedrin’s opera Lolita is obviously very different from Debussy’s in subject and music substance, although forbidden longings and a tragic denouement are also present here. Shchedrin began working on the opera in the early 1990s, inspired by Mstislav Rostropovich – and the opera received its premiere in Stockholm in 1994. It took it more than 25 years to reach the stage of Mariinsky Theatre (where almost all operas of the composer have been presented in recent years), but in February 2020 the audiences could finally see production – in transferal from National Theatre of Prague (2019) with the same soloists. Shchedrin used Nabokov’s Russian text for his own libretto, while subtitles interestingly are pasted copies from its English versions that occasionally causes discrepancies. Musically the opera is very eclectic. It pays homage to Wagner, adopting a system of leitmotifs, and to Janaček, through slowing down the tempi and at first sounding partly monotonous, tries to render patterns of human speech in music. It also, like Varèse, introduces renditions of street sounds in orchestral writing. Ideologically, Shchedrin weers away from Nabokov’s refusal to moralize and follows Russian tradition represented Dostoevsky where every criminal story should help the reader’s growth by distinguishing between right or wrong. In this Lolita we see the character Humbert as a new Raskolnikov who is allowed to speak before his judges while living through the tormented hell of his memories, but in the end, similarly to Goethe’s Faust, seeing a glimpse of salvation in a children’s chorus singing an ode to Mother Mary. And indeed, this constant turbulent oscillation between devil and angels, sombre and humane sides of the soul are at the core of Schedrin’s operatic creation.

The set design (Boris Kudlichka) is minimalistic, influenced by avant-garde European tendencies, but also by the subject matter of the opera. The Mariinsky stage allows many objects placed on it at once, but all of them are ‘disembodied’, don’t belong or sometimes are literally only half of the thing they are supposed to represent, increasing the voided feeling we have from the very start. Shchedrin places the opera in the ‘guilt’ circle by starting it with a scene where Humbert is shooting his rival, the playwright Quilty, while the latter is having a bath. The main character is feeling only responsible for Lolita’s seduction, but not for this crime (such double standards are again similar to those of Raskolnikov). In this opera Humbert is always in some kind of dialogue with a chorus of men, that act as his unearthly judges and appear as his dark angels of conscience every time he speaks about his past. Shchedrin makes this a monologue opera, despite presence of multiple characters, as everything is perceived through Humbert’s eyes. The musical material might seem monotonous in the beginning, but widens and gains variations further on, as we discover ghosts hidden in the protagonist’s memory. Everyone and everything here is the shadow of Humbert’s recollections –halved carcasses of cars, a similar motel for everyone where the couple lives in, and a very simplistic (almost a caricature) interior of Charlotte’s house that folds and disappears, like a house of cards. The further the opera develops, the barer the sets gets, living us with a representation of a car (cabin only) and the same motel with the same sign (The Enchanted Hunters). Then the stage bares again, every object disappearing, apart from the bench where Lolita and Humbert meet for the last time, and the chorus of girls (all aged similarly to Lolita) surrounds Humbert,– not judging him, but rather praying to the Godmother for him. This chorus is accompanied by a set of videos of modern teenagers with cheerful or sad, mischievous or mysterious glances – all having lives and futures of their own – that passage of time Lolita was deprived of.

Lolita. Photo by Natasha Razina.

This very moment gives a raison-d-etre to the whole opera. It becomes its redemption, purification, and clearly bears its moral message intended by Shchedrin. Without this moment, it the opera is difficult to watch, despite the minimum presence of openly sexual or violent scenes. Its dramatism lies in its constant inner intensity that, when burst open, is even more frustrating to watch. All the possibilities of exciting reading that the reader of Nabokov might secretly experience are swiped clean by Shchedrin, as we see Humbert (Pyotr Sokolov) having a an erection when Lolita (Pelageya Kurennaya) rhythmically sings Car-men, Car-men with him while naively bouncing her leg on his groin. This is followed by moments in a motel cabin that reveal the horrific violence of the trespassing of human dimension that desire drives Humbert to. We see a tired and disheveled Lolita who wants to sleep or have a drink filmed by Humbert on a camera (him filming her earlier in a bathroom reveals his voyeristic desire and it is these videos that are found by Charlotte before her death), and then he jumps violently on her with lights dimming, thus crossing the divide once and for all. It is really amazing how both Shchedrin through his music and the director (Slava Daubnerova) manage to show the horror of this trespassing without excessive naturalism, but that is why this opera is a continuous strain on us as listeners and observers, as we almost commit the crime and suffer together with Humbert.

Lolita. Photo by Natasha Razina.

Considering all mentioned above, Pyotr Sokolov and Pelageya Kurennaya both are outstanding in their respective roles. Sokolov shows the contrast between outward humility and the relative youth of his character (we tend to forget his is in his 30s) and the hell that torments him inside. His violent streaks change the singer, making both his vocal performance and behavior on stage intense, deterministic and thought-through. Sokolov also acts very powerfully in the scenes where he is in dialogue with the chorus of his conscience, aptly switching from between ‘action’ and ‘recollection’ modes. He is contrasted by devilish Claire Quilty sung by a Chech tenor, Aleš Briscein, who reminds us of Britten’s Death in Venice(based on Thomas Mann’s tale of desire) where the protagonist is also haunted by figures that represent the darker side of his conscience. Pelageya Kurennaya who has a firm presence in Mariinsky’s repertoire is the discovery of the evening, as she manages both to show the gradual decline from girl to fallen woman, striving to retain her teenagehood till the very end. Kurennaya has a wonderful, deep mezzo-soprano that goes in stark contrast with her slight and short built and teenager curls (a wig for the role). The woman in her is powerfully revealed through her voice while her boyish movements and childish moodiness cover the sufferings of the incongruity of her situation till the very end when in her white dress and a bump she finally meets with the woman she was forced to become. Darya Rositskaya does a very good attempt at farcical characterization with singing the mother Charlotta – a frustrated middle-aged woman. One could suppose that it was quite a challenge for Valery Gergiev to conduct this opera, but he is not a newcomer as far as Rodion Shchedrin is concerned as the maestro has been in the ochestra pit for all premieres of the composer at the Mariinsky – and thus he lives through the torment that music powerfully reflects and takes the musicians and singers with him.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yulia Savikovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.