The Second World War is central to our national imagination, yet it has been oddly absent from our stages recently. Not anymore. Nicholas Wright’s new play, an adaptation of Patrick Hamilton’s 1947 novel about lonely English women and confident American servicemen, premieres at the Hampstead Theatre in north London, and effortlessly evokes the world of the Home Front deep in the middle of total war. Yet adapting novels is a risky business, mainly because their tone is so hard to convey without using paragraph after paragraph of prose, and Wright struggles to give us a convincing stage version of an obscure novel he loves perhaps too much.

The Slaves of Solitude is set in the winter of 1943. We are in the Rosamund Tea Rooms boarding house, in Henley-on-Thames. Miss Roach, an educated middle-class “worthy spinster dame” who works in publishing, has fled London during the Blitz and has taken up residence here. She is lonely, and has little in common with the other residents: odious Mr. Thwaites, a pompous, prejudiced and pretentiously phrase-making old man, Mr. Prest, a retired actor who misses the bright lights of St Martin’s Lane, two guests Miss Steele and Mrs. Barratt, and Mrs. Payne, the owner.

In the dining-room, the guests gather for meal times and exchange barbed comments and pieces of gossip. They also clash over politics: Thwaites is a hardline Tory and Miss Roach is a liberal. She thinks the Soviets are a good ally against the Nazis; he thinks all commies are a threat. But the equilibrium of the place is disturbed when Miss Roach meets Lieutenant Drayton Pike, an African-American soldier stationed nearby, and Vicki Kugelmann, a German migrant who has been living in England for a number of years. An emotional connection develops between the three of them, which also—during one drunken night—draws in Mr. Thwaites, resulting in sexual jealousy, frustrated attraction and two offers of marriage. But the darker, and more bitter, emotions of loneliness and hatred combine to scuttle any hopes of a happy ending.

Lovers of Hamilton’s novels will recognize the psychological territory, mapped out in empty bottles of alcohol and overflowing ashtrays. The slightly greasy glamour of the down-at-heel and the social outcast, observing conventional life with an intelligent eye and a heavy heart, craving a more fulfilled life, wishing they would be more present, are all in the story. The main trouble is that a few brief hints apart, they are absent from this stage version. There’s little distinctiveness in the writing and no real sense of Hamiltonian futility. Worst of all, the special relationship between the UK and the USA lacks any contemporary resonance.

Instead, there are a couple of scenes of melodramatic excess, and some nasty and cruel passages that fall flat because the play’s characterization is too thin and too unconvincing. Miss Roach, for example, is meant to be a sad loner, a prude and a bit prim, so when she says that she enjoys sex with the American, it simply beggars belief. Near the end, there are a couple of short passages about hatred, which makes your ears prick up in hope, but none of them are developed. The plotting is clumsy, and the dialogue is a bit too thin and perfunctory. I like the character of Vicki, who gives an enjoyably Continental perspective on English manners, being more open-minded and humane than this island’s homegrown puritans, but it’s not enough.

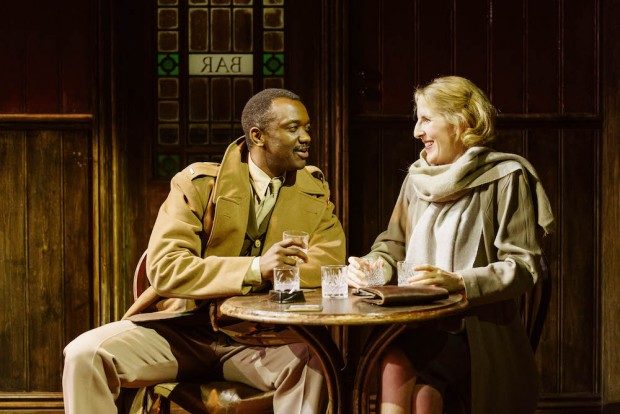

Although the press night was slightly jinxed, with Tim Hatley’s trundling scenery getting a bit stuck, the cast of Jonathan Kent’s uninspiring production do their best with some rather dull material. Of course, Fenella Woolgar is too good an actor to fail to breathe life into Miss Roach, and she does give some sense of the woman’s dusty existence and her thwarted dreams. It is a performance of considerable nuance and subtlety. Likewise, Daon Broni lends Lieutenant Pike a rugged charm, while gradually revealing his darker side, and you can see why Americans were a magnet for English women. Lucy Cohu’s flirtatious Vicki is perhaps a touch too much of a caricatured foreigner, and Clive Francis’s powerful Thwaites has too little to work with.

If The Slaves Of Solitude is under-motivated and occasionally over-dramatized, it still manages to evoke some of the details of wartime: the blackout, the rationing and spam fritters, the bad news from the front and the agricultural volunteering. Soviet allies, details of bombing and the British love of pets all get a name-check. The way that the experience of war affects all aspects of your psyche is strongly conveyed, and some of the frenzy of a hothouse society also comes across well. But the main feeling is impatience at the crudeness of the adaptation, the weakness of the plotting and a distinct feeling that this play is a dud.

The Slaves of Solitude is at the Hampstead Theatre until November 25.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.