Ibrahim Miari, son of a Palestinian Muslim father and Jewish Israeli mother, grew up in Israel, became an actor, a playwright, a Sufi dancer, and an educator who now lives in the US.

His one-man drama, In Between—directed by the much-talked-about Elena Araoz, who works internationally—presents intermarriage and growing up in two cultures against all odds.

This drama became so successful that it toured internationally, including Germany, Austria, Ukraine, and the U.S. Ibrahim’s suitcase, filled with numerous props, including a giant hand puppet, makes countless scenes from his life come alive through his extraordinary capacity to act many different roles—including Ibrahim as a little boy, his old grandmother, and an Israeli airport interrogator.

The press and major universities responded to In Between in remarkable ways:

“Here we have a dramatic piece that makes a valuable contribution to our awareness of the kind of issue which we are so often only too happy to ignore.” – Jewish Telegraph, Leeds, UK

“Ibrahim’s own story helps us see the importance of appreciating and dignifying the rainbow of diverse narratives and personalities of our neighbors nearby and around Earth.” – Jewish-Palestinian Living Room Dialogue

“With deft and charm, he transcends today’s political distractions and reminds us of the deeper inner struggles that link all of humanity.” Public Programs Center for International Studies at M.I.T.

The students and faculty at Brandeis University responded positively to In Between—which tackles taboo subjects about “identity, belonging, cultural and religious conflict in Israel and in our own diverse Jewish community”—that they want to invite Ibrahim back “for many years to come.” BIMA and Genesis at Brandeis University

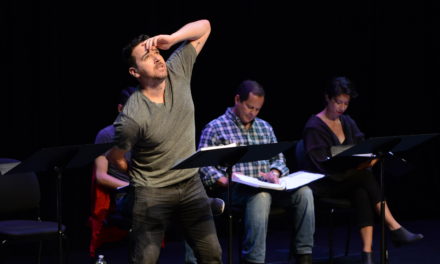

Ibrahim Miari working with a giant puppet that takes on Arabic & Israeli, Islamic & Jewish roles. Photo by Mark Garvin.

Avraham and Ibrahim: Becoming aware of different identities

Henrik Eger: When was the first time you realized you liked acting?

Ibrahim Miari: My whole life I knew that I wanted to be an actor. I was the one in my family who did impersonations and made people laugh. I was always chosen at school for class theater plays. My first memory on stage was second grade—Mother’s Day. I was pulled up to the stage to dance to a well-known jingle. When I saw the entire school in front of me cheering, I felt I was home.

Henrik: You grew up in Israel as the son of a Palestinian Muslim father and a Jewish Israeli mother in a country that is not exactly famous for treating Palestinians with respect. Could you give an example of a tough moment where you were made aware that you are a Palestinian?

Ibrahim Miari: I grew up in a Jewish neighborhood. We were one of two Arab families in that area. I was sent to a Jewish kindergarten at first, and there was mutual respect between all neighbors, mostly of Middle Eastern backgrounds—Moroccan, Libyan, Tunisian, Egyptian, etc.—alongside some Ashkenazi families.

I was lucky enough to grow up with children my age where we shared various activities, including Jewish traditions, like building Sukkah. I never felt marginalized in my early childhood. However, I remember an incident: after I helped my neighbors build a Sukkah, I was told by one of the more religious peers not to enter it because I was not Jewish.

Henrik: You were born “Avraham” in Acco, Israel, and attended Jewish school until the age of seven. At eight years old, your name was changed to the Arabic spelling, “Ibrahim,” and you were enrolled at an Arabic School where Israeli Independence Day is commemorated as “Nakba Day,” or the “Day of the Catastrophe.”

Ibrahim: I address this topic in my play. From an Israeli viewpoint, a national celebration day for Jewish people made sense to me. However, the contradictions and ironies of this day only made sense to me later on in my adult life, especially as in Israel, 20 percent of the population are native Palestinians. You cannot escape the celebrations and the fireworks by the Israelis. It has become even more ridiculous with state laws preventing people from waving Palestinian flags, acknowledging the catastrophic day, or allowing the schools to teach about Palestinian history.

Henrik: Similarly, could you give an example of a tough moment for you as an Israeli?

Ibrahim: If you are a Palestinian/Israeli citizen, there is no such thing as “a Palestinian” or “an Israeli,” as we all share common realities. Yet, the more I interacted with Palestinians at peace camps from the West Bank and East Jerusalem in the United States, the more I became aware of my privilege as an Israeli citizen.

Henrik: You grew up in the theater world and studied and worked with the Acco Theatre Center’s Actor Training Program in Israel for twelve years. What were the main influences on your life from those experiences?

Ibrahim: I have been involved in creating theater connected to the Middle East conflict, and in many ways have protested against the dominant norms of society through the arts. While working with Acco Theater Center as a member of an ensemble, we created many shows that addressed injustices, like the play Arab Dream. Later, I wrote and directed a play called Private Moment about a Ukrainian actress who married an Arab citizen of Israel. She first lived in an Arab Village, then moved to the city and interacted with Jewish people. The play reflected how she experienced both cultures and all stereotypes she had to endure from both sides.

Sufi dance, Sufi philosophy—making compassionate choices

Henrik: Having been brought up with both Islam and Judaism, what drew you to the Sufi religion, philosophy, and practice—especially through dance?

Ibrahim: I was attracted to the Sufi dance first and then Sufi philosophy. I was introduced to different meditations, especially sacred dances, even though I do not consider myself a devoted Sufi. However, it had a big impact on me as a person and as an artist, because meditation teaches us to become mindful and aware of our judgments and negative cycles and patterns. Once I became aware, I started practicing more mindfulness. I also created a space for making more compassionate choices.

Henrik: What inspired you to perform in a Sufi mode and direct several drama programs in peace camps in Canada and the United States with Israeli and Palestinian high-schoolers?

Ibrahim: As I am fluent in both Arabic and Hebrew and familiar with both cultures, working at these camps felt like the right and natural thing to do. I believe in sharing personal stories. To quote an old saying, “An enemy is someone whose story you don’t know.” Aware of this insight, I made it my mission to help cultivate a culture of mutual listening and understanding. We can eliminate a lot of the stereotypes and prejudices when we search for common ground.

In many of those camps in the U.S. or Canada, Palestinian and Israeli youth meet each other for the first time—often leading to friendship and new insights. However, the participants also realize that they live only a few miles from one another in the Middle East, but interactions among them are difficult, prohibited, or impossible.

Leaving the Middle East, growing new roots in the U.S.

Henrik: What made you leave Israel and move to the U.S.?

Ibrahim: I met my wife at one of the peace camps. If it wasn’t for her, I would have moved to Germany because at that time I had a contract to work with a German theater company. However, I chose love, which led to starting a family, and my Master’s degree in theater.

As an educator, I was always intrigued by international collaborations, learning more about other cultures, and expanding my perspectives and knowledge of the world through the arts. I never intended to leave Israel. However, I had blessings from both my family and my theater community to leave home for the U.S.

Henrik: Did you experience any culture shock in the U.S.?

Ibrahim: The culture shock for me came through language. My English was all right, but I had to further my linguistic skills to better express myself. Even though I improved a lot—having an accent, I still feel limited in the U.S.

Henrik: Could you give some examples from your life that inspired you to write the semi-autobiographical drama In Between?

Ibrahim: For over a decade, I have been involved in creating theater connected to the Middle East conflict, and in many ways have protested against the dominant norms of society through the arts. However, I have always felt the need to go deeper, beyond the political, to the personal life stories that express authentic feelings and offer an opportunity for connection and understanding.

The process of creating In Between has been a dynamic one. What began as a series of vignettes about my parents and my childhood in Israel took a new shape with the intrusion of two realities in my own life.

First, an incident in which I was held up in Israel for hours at airport security and interrogated about my identity. Second, a rather more welcome intrusion, the planning, and preparation for my wedding, another process in which my identity created the impetus for many conversations and negotiations.

In Between, a one-man drama

Henrik: Your thought-provoking play In Between traces your evolution as a bridge-builder between different cultures and religions. You did not shy away from presenting a shocking experience with an interrogator at an Israeli airport and how it impacted you.

Ibrahim Miari, as an Israeli airport interrogator with blue gloves checking out a Palestinian tambourine. Photo by Mark Garvin.

Ibrahim: Having flown in and out of Israel many times during the last 20 years, I know what to expect every time I approach the airport. It has not gotten any easier.

On one occasion, I had come to the airport directly from my Jewish cousin’s wedding in Tel Aviv. The security guards were puzzled: I was originally from Acco; I studied in Boston; my parents had an interfaith marriage; I was a Muslim; and I had just come from my Jewish cousin’s wedding with henna on my hands? The officials actually said, “When you say cousin do you mean, cousin blood relative, or, Arab and Jewish cousins?” They did not release me until the last minute, making everyone wait for me. And no, I rarely make it to a Duty-Free.

Henrik: You developed In Between in 2009, premiered it in Boston, USA, in 2012, updated it recently, took it to theaters in Europe and North America, and even won “Best Show” award in 2018. Congratulations.

Ibrahim: Thank you. The play is a dynamic one. I am sensitive and attentive to current events, and I find ways to improvise and make the drama relevant. A recent example: on my performance at the Walnut, I incorporated the 2018 Israeli Nation-State Bill [“which specifies the nature of the State of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people”] into an integral part of my monologue about not being Israeli enough. I’ve added, “now it’s according to the law.”

Since then, I performed In Between (Dazwischen) at the international monodrama festival THESPIS as part of its contemporary “one-man-shows” in Kiel, Germany, and won the “Best Show” award in November. In May 2019, I went to Kyiv, Ukraine, and performed at their Solo Shows Festival (SoloFest).

Henrik: How did Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Theatre, the oldest continuously operating theatre in the English-speaking world, the oldest theatre in the U.S., and the most subscribed theatre company in the world, discover you or find out about your work as a playwright?

Ibrahim: I auditioned for The Humans. Once I got the role and they got to know me better, I mentioned In Between to Mr. Bernard Havard [president and producing artistic director of Walnut Street Theatre]. He promised to look into it. One day, he called and offered to produce it.

Transcending the problems of the past

Henrik: Were there people in the Palestinian or Arab world who did not appreciate your bridge-building between different cultures and religions? If so, how did you handle any criticism or perhaps even hostility?

Ibrahim: I wouldn’t say I got hostility for trying to bring people together to share stories. However, some people expressed reservation or tried to minimize to what extent our peace camps are effective. It’s an ongoing research project, and there’s still a lot to learn about these programs and models, but each 1,000-mile journey starts with one step. I hope I am contributing something to cultivate dialogue.

Ibrahim Miari, in a scene of an arrest at Ben Gurion Airport. Photo by Mark Garvin.

Henrik: Could you give an example where everything came together for you, where all the difficulties of the past led to a transformation that is reaching a wide audience on both sides of the divide—even though cultural clashes and misunderstandings most likely will continue for you and all of us?

Ibrahim: It all came together when I realized that the process of getting married and trying to explain myself at the [Israeli] airport were two similar events in a lot of ways: my identity and beliefs were at the center. Once I decided which stories I would focus on, the play kinda wrote itself.

The theater is a mirror, and my play touches upon issues such as identity, culture, religion, traditions, and the tensions between Jews and Arabs, Israelis and Palestinians.

I believe that people can relate because I choose to share a personal story. I don’t even try to talk about politics.

The reality is that we all have our agendas and ideas of how things should or shouldn’t be, but the more personal I get, the more people can open up and listen—not necessarily to agree with me, but hope to hear something new, to reflect on it, to laugh at it, perhaps even to be upset about it. That is why I keep performing the play.

Henrik: Many thanks, Ibrahim. Shalom and Salaam—wherever you take In Between on this globe.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Henrik Eger.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.