When Milo Rau arrives in a city, he attracts the attention of theater journalists, professionals, and theatergoers who follow the latest trends. This is definitely the case with his recent visit to Madrid. In fact, he has been in the city twice in recent months with two different companies. The first visit was in early December 2019 with Orestes in Mosul, produced by Neederlands Toneel Gent or NTGent, where Milo is Artistic Director. The play was included in the Festival de Otoño of Madrid. The second visit was in January 2020 with Empire, produced by his company International Institute of Political Murder (IIPM).

Both shows are similarly built. They have actors and scenography that includes a house and screens where close-ups and mid-shots of the cast are projected. From time to time, these shots are combined with other images. In the case of Orestes in Mosul, they are of local Syrian people who were selected to be part of the cast, and scenes of devastated Mosul. The short films are a way for Milo Rau to incorporate local actors and locations on the tour of the play. In Empire, the images come from a variety of sources, from Syria to a Theo Angelopoulos film. They relate to the actors’ and actress’ lives.

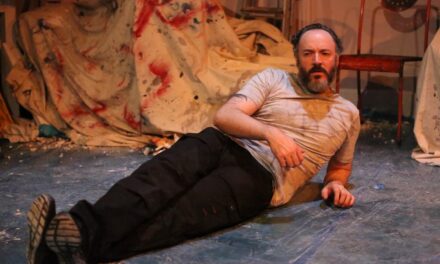

However, the sensation created by each show is completely different. Orestes in Mosul utilizes pretentious staging, the purpose of which is unclear. Everything looks unnecessary. Many questions arise: Why should Orestes be staged in Mosul? Why is it necessary to mix actors from many nationalities, languages, and so on? Why is a house needed on the stage? Why do some actors go into the house – which means the audience cannot see them – but their voices are heard? Why are they filming what the actors do inside the house to show on a big screen, instead of just showing the action on the stage?

Orestes in Mosul by Milo Rau. Photo by Fred Debrock.

Furthermore, it is difficult to link Orestes’ revenge against his mother, and what is happening in Syria, to the Orestes’ trial after killing his mother and her lover. In the end, one might think that this play is included in the festival simply because of the name of the director.

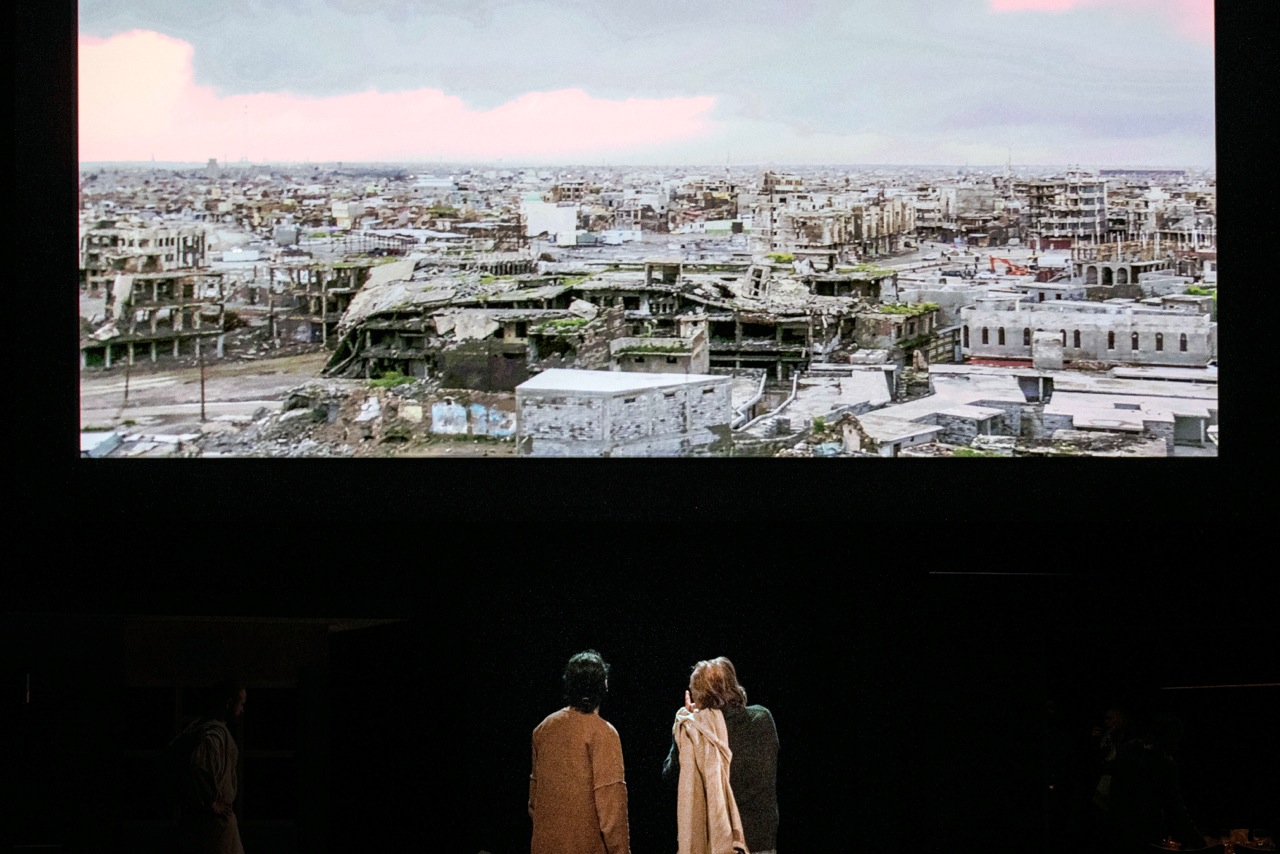

In contrast, Empire really works. Again, the performers represent different countries. They speak different languages as they tell their real-life stories on stage. They explain where they are from, how they got their nationality, how they became performers, how important performing is to them, and what impact theatre has had on their lives. They don’t tell their stories to each other. They don’t interact. They perform monologues to a camera that is filming them. Meanwhile, their talking image is projected on a big screen hanging above them.

All of the performers live in Europe, but the Syrian war is present because two of the performers come from Syria. They have absconded from the war and death that menace their lives. The other two actors are from European countries, but their stories are those of people who were forced to emigrate. They share stories of their parents who ran away from Soviets and Nazis, and their own history of escaping from European dictatorships of the 20th century.

Empire. Photo by Marc Stephan.

Their monologues are mesmerizing. They sound like psalms. They are repetitive and boring and hypnotic at the same time, and too long for most of the audience. Listening, the audience rests in silence as if they were attending mass. They observe how the ordinary stories of these performers have been influenced by history, how governments, politicians, powerful people, and targets were imposed on their lives. At the same time, the cast realizes they have lost their houses; they do not have a place to go back to. In addition, they realize that their backgrounds do not help them to assimilate into new places. Consequently, the spectator who empathizes with the performers and their stories, realizes that they could easily be in the same situation and have similar lives and feelings.

Yet, why do the same playwright and stage director produce these different results? Why is the first result disappointing, and the second fascinating? The answer could be that Orestes in Mosul results from visiting conflict zones and hopes to alleviate suffering through theater. It seems to be made with a sentiment of pity and sorrow for Syrian people and the situation they live in. Nobody asked Rau and NTGent to focus on compassion; that is not the purpose of the festival. Yet, the main purpose of the production does not appear to be theatricality, or to stage a play.

Empire is completely different. It is presented theatrically, not just as a workshop in a conflict zone to help alleviate the suffering of the people. Empire tells a story, and Orestes in Mosul shows a story – that is the key issue. Good theatre is not just made of compassion, pity and/or sorrow. It is a fiction that lets audiences understand what has happened to them, instead of actually experiencing what happens, as Federico García Lorca suggested.

Edited by Carrie Klewin Lawrence

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Antonio Hernández Nieto.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.