The family celebration drama is a genre that had its heyday in the 1960s when social mobility made the situation of upwardly mobile children in conflict with their working-class parents immediately recognizable. One of the market leaders of this trend was polymath David Storey, whose In Celebration (1969) is a classic example. In that play, three brothers return to visit their parents, in a Yorkshire mining village, on the occasion of their 40th wedding anniversary. With The March On Russia, which was first performed two decades later in 1989, Storey revisits this family situation.

This time, it’s the 60th wedding anniversary of the Pasmores, a couple who have retired to a bungalow in the Yorkshire countryside. He is a mildly leftwing miner suffering from an incurable lung disease while she is a working-class Tory housewife. Their three children visit them and family tensions soon surface. Colin, who is an academic and writer, suffers from depression and an inability to connect back to his working-class roots, while the rather sour Wendy is a local council member who has abandoned the Labour Party in favor of acting as an independent. The third offspring, Eileen, is the youngest and seems happy being a housewife and mother.

Nothing much happens. The children arrive (in the case of Wendy and Eileen unexpectedly); they take their parents out for a meal at a local hotel, and then stay the night; in the morning, they all head off home again. As they bicker and occasionally argue, there are glimpses of the wider world outside this small bungalow and Pasmore’s years of work as a miner. His wife is a Thatcherite who good-humouredly advocates the “on yer bike” philosophy made popular by Norman Tebbit, the Iron Lady’s employment minister, and disparages the culture of Welfare dependency. And, as the title of the play suggests, Pasmore’s early years were spent fighting as a British conscript on the side of the Whites in the Russian Civil War, which followed the Revolution of 1917. Sent by Winston Churchill to save the Tsar, the mission was not a success.

The memory of this Russian adventure, being a powerless cog in vast events that you cannot control, is an apt metaphor for both the older generation, whose struggles with poverty are eloquently, if bitterly invoked by Mrs. Pasmore and for the children. Colin has had a successful career but feels acutely alienated from his own life, unable (for all his educational achievements) to articulate his depression or get help for it. He often seems utterly helpless. Likewise, Wendy, who has been unable to have children, cannot control her fertility and, according to the family’s rather harsh wisdom, has chosen divorce and local politics as an outlet for her frustrations. Only Eileen seems happy in her modest life choices.

Storey’s play is a loving portrait of a family not unlike his own. He carefully and perceptively shows how the constant bickering of the father and mother has been calibrated by 60 years of marriage so that it’s more of a ritual of communication than an expression of fresh emotions. Their arguments reveal their affection and their mutual dependence on each other. Gradually, some sadder facts emerge, but this is not a play where a major revelation shakes the edifice of the family. It’s quieter than that, more wintery. In the end, the memory of the march on Russia becomes a lodestone that anchors the parents in a reality which is beginning to dissolve as they age.

The children represent both social mobility and various aspects of 1980s society. Colin is a man whose material success brings him anguish, illustrated by the story of his having something of a panic attack on the plane taking him to New York for the launch of his book, while the women represent some rather clichéd views of femininity. Storey seems to suggest that female happiness is more often found in domesticity and kids, than in career and independence. This feels like an oddly reactionary point of view.

The March On Russia is a bit of a retro piece. Not only is its sensibility rooted in the 1960s, but it is also aesthetically old-fashioned, and not in a particularly good way. A lot of the exposition is clumsy, and I lost count of a number of times that these family members told each other information that they would all surely already know. So although most of the exchanges, especially those between the 80-year-olds, have the scent of authenticity, the lack of a compelling story makes watching this a bit of trial. I spent much of the second act longing for a bigger argument, a bigger reveal, a bigger theme. But no, everyone is too polite and under-stated for their own good.

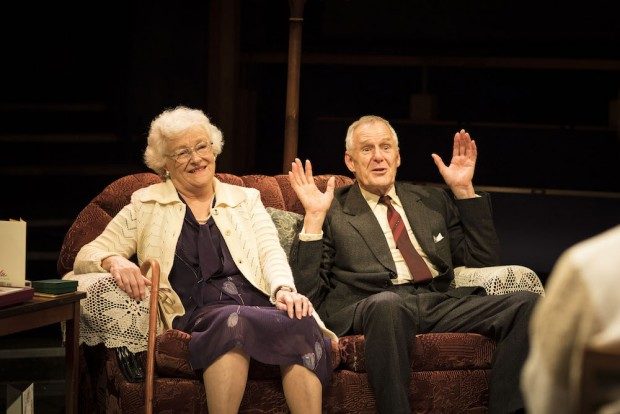

Still, it’s hard to fault Alice Hamilton’s meticulous and empathetic production, for Up In Arms theatre company. Although the play feels a bit cramped in the playing space, where designer James Perkins has positioned a real coal fire, the atmosphere is suitably intimate and the acting natural and unforced. Ian Gelder’s Pasmore is a study in resignation and futility, and balances perfectly the rhythm of his dialogues with the rough poetry of Storey’s words, and has the ability to use a grimace or an upward glance of the eye to show feelings beyond words. Even more convincing is Sue Wallace as his wife, both severe and precise, a house-proud Yorkshire woman rooted in common sense. Colin Tierney (Colin), Sarah Belcher (Wendy), and Connie Walker (Eileen) each convey the individual particularities of their characters. This is very much a show for those who like their drama to be subtle and understated, with hidden depths and emotional reticence. Others, like me, might find it all a bit too underwhelming.

This post originally appeared in Alex Sierz on September 22, 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.