Recently London was abuzz with the new project of the London Russian Ballet School — The Romantic Revolution — A Charitable Gala evening of ballet performances at the Palladium Theatre featuring both students of LRBS and stars from the Bolshoy and the Mariinsky Maria Alexandrova, Vladislav Lantratov, Katerina Krysanova and Semyon Chudin. The reactions of children from unprivileged backgrounds who were for the first time invited to see ballet performances, were very emotional and very enthusiastic — something precious to treasure. Our correspondent, Valeria Strachevska, met with Maria Alexandrova, who shone onstage as Carmen. The celebrated ballerina shares her thoughts on life and ballet, differences in Russian and British mentality and culture.

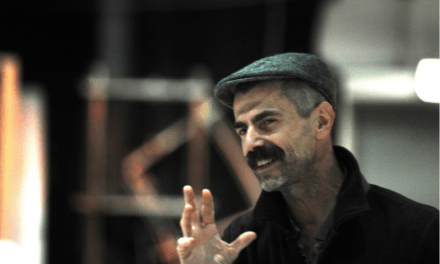

Maria Alexandrova, Vladislav Lantratov in Carmen at the London Palladium, 18 September 2017 @Courtesy LRBS.

Maria Alexandrova, Vladislav Lantratov in Carmen at the London Palladium, 18 September 2017 @Courtesy LRBS.

VS: The Gala night of the London Russian Ballet School was a form of gaining experience in performing. Young students of the LRBS danced in the heart of London, in a beautiful theatre, to the full theatre audience and, most importantly – they also performed solo. However, the traditional Russian school of ballet has a different system of introducing dancers to the stage. One should first dance in corps de ballet for several years before moving to leading roles.

MA: The London Russian Ballet School is an utterly special managing system. There were not enough people to stage complex scenes with lots of dancers in them. This explains why the programme predominantly consisted of individual dances. From this perspective, private education has its own advantages. Ambitions, ideas, and opportunities can be explored to the maximum. This also allows for certain digressions from the strict rules and traditions of the academic ballet.

I liked the concept of the Romantic Revolution a lot. Everyone was excited, including the students, teachers, parents, and even us. Apparently, for the Russian ballet overseas this remains the only available platform which facilitates and promotes dialogue between generations of dancers — a proper way of passing the experience down to new performers.

VS: Do you think that working with the stars, who have danced for a long time, can put limitations on finding the students’ individual style and manner of dancing?

MA: Not at all! It is absolutely necessary to know that the world has existed before us. Unfortunately, the new generation can be very self-centered in thinking that they create history. It is possible that at some point and to some extent, each generation makes the same mistake. But for a ballet dancer, it is very important to remember that the ballet has existed for a long time, that there existed people who created it, who developed it as a school, laid down the foundations of its scholarship and formed its traditions. For those who chose to study the Russian ballet school tradition, it is of paramount importance to know that the Russian academic ballet school actively developed and came to prominence in the 1930s (due to Agrippina Vaganova) and that the method and system of teaching ballet has changed very little since then.

VS: Is the existence and development of the Russian ballet possible outside Russia? Or is it a utopian idea?

MA: It seems that the Russian ballet can exist properly only on the Russian soil, and by that, I mean mainly Russian people. Anna Pavlova used to say that Russian people have a very special “dance-ability” (“tantsevalnost”). When Russian dancers and teachers move abroad, in the end, they work with a different material.

VS: And this material is much more diverse than in Russia. It feels like the Russian school in London is more tolerant and democratic.

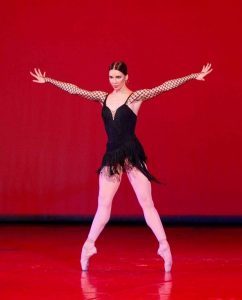

Maria Alexandrova as Carmen. Photo by V. Komissarov.

MA: It is not about democracy, it is about compromise. It is very common these days to talk about our rights and equality. From this perspective, it is very hard – especially for private schools – to find a right balance between the high quality of education and high level of client service. But ballet has traditionally been a very tough profession. It is almost inevitable that a child will be cracking under the strain or being overwhelmed with the routine of classes. A child will never understand why he or she should do the same movement 200 times in a row. But this is how one builds one’s professional foundation. It is like an architectural structure. We enjoy the beautiful façade, but we can only guess what the building rests on. It is very specific to the ballet that already at the age of 10 children start building up their career and work for their professional success if they see dancing as their future vocation.

VS: Do you think a 10-year old child is capable of choosing his/her career? In many cases, children are brought to ballet by their parents. How did you become a ballerina?

MA: Oh, I was one of those (perhaps very few) children who had chosen the life path themselves. At the age of 8, I made my own, independent and conscious decision to dance in the ballet professionally. I was not dreaming about swans, pointe, and beautiful costumes. Not at all! For me, it was a way of shielding myself from the world which I could not understand. Plus, I enjoyed that it was a silent form of communication with the world. I saw it as a form of art that could tame me – my passionate, fiery temperament. Vladislav’s story is different. He was born to a dynasty of dancers: theatre was present in his life from early on, so, in a sense, his professional choice was a matter of predestination. To be honest, it seems to me that the main thing in this matter is the purity of intention. In the end, we are what we believe in.

VS: What if the teacher and the parents believe in the child but the child him/herself is not willing to dance?

MA: It is impossible to force a child to do anything. Certainly, not to dance. Ballet (or dance in general) is the only form of art that is responsible for all three forms of being: intellectual, spiritual and, of course, physical. Dance is a search for harmony, search for oneself as a human. And this is a journey that a child should make on his own. It is entirely up to him/her whether he wants to do that. At some point, I was asking myself: why don’t people tell what they think in the right moment? Why don’t they try to persuade? And then I realized that there should always be room for the freedom of choice.

VS: Did you choose your own roles to dance?

MA: When I was studying, we had a very strict discipline. It was always for the teachers to decide who would dance what. Of course, good teachers always take tempers and abilities of their students into consideration, but in the end, one would dance what he or she was told to dance.

VS: Which roles are easier for you to dance – classical or contemporary?

MA: I prefer stories with a plot. I believe that the narrative dictates time, brings out the humanity. I know that narratives in classical ballet can be very naïve but it is something that keeps you in shape, allows you to focus on performance rather than on the psychological aspect of your role. Contemporary ballet has unbelievable, almost unlimited freedom to it, but it is very demanding physically, perhaps even more so than the classical ballet. It is also more challenging psychologically: contemporary ballet does not allow one to hide behind the performed character but propels one into exploring, revealing and questioning oneself.

VS: You probably noticed at the gala that the students were much stronger and more confident when dancing contemporary productions. Can you explain this?

MA: It is a matter of searching for internal limitations, frames. We, Russians, we live in a very rough climate and have always been making our social life and rules very strict, very regulated. Probably this is what makes us prone to philosophy: we invest a considerable effort into soul-searching, trying to expand our internal horizons, so to speak. We find comfort in strict externally imposed rules. And for this reason, we feel very confident at the ballet. Here [in the UK] the situation is quite the opposite. The society for a very long time has been moving towards liberation, and it is the world outside which is being expanded. Probably this is the reason why the students here are much better at the contemporary dance than at the classical ballet.

VS: In the hierarchy of performing arts, ballet, perhaps, ranks as the most senior and serious. Does it mean that ballet should only be about the eternal subjects, such as love, justice, death? Should ballet also address the burning issues and pressing problems of today?

MA: I personally believe that when ballet becomes politicized, it grows very boring. Ballet is a form of reconciliation. No words – no conflict. I still have a vivid memory of a moment, when we danced at a big corporate party in the USA. Apart from us, there was a variety of performing artists and musical bands from Hawaii, Japan, and other countries. I remember that after the performance, they started playing their musical instruments together and all of them began dancing. We joined in, as well. Eventually, all those people from five continents were celebrating together and clearly understood each other, and experienced the same emotions in this primal act of dance. That was unforgettable!

VS: The idea of finding a sense of unity in a dance brings me back to the gala. What was happening behind the curtains during the performance? How did you communicate with the young dancers?

MA: Behind the curtains, we were mainly occupied with our professional issues: checking the floor and lighting, preparing the shoes and so on. Dancing in a new place is always very stressful. Unfortunately, there was not much communication with the ballet school students. However, there appeared – quite unexpectedly – a great communication with the audience. All those children’s reactions. Fantastic atmosphere!

VS: It seemed that everyone in London was discussing that kiss on the following day.

MA: Haha, the second kiss was staged, but the first one wasn’t planned at all. That was in the air! Everyone dreams about miracles, simple everyday miracles like a kiss. Everyone wants to wake up in the morning and be kissed by someone.

VS: People could see the surprise on your face when that child started crying. I guess that was quite unusual for you

MA: Yes, a crying baby – that was very unexpected. But I accepted that child. I realized that the child was not looking at me at that moment, but I was happy that he/she was there. The best thing about the project were children. They came to the theatre for the first time in their life. It is very important, as theatre is something that is happening here and now, there is something magical about the momentary, fleeting character of the ballet. Even if one sees the same programme several times, each time it will be a completely different experience.

VS: Even if just one child out of these 700 will end up doing ballet, this will already be an achievement.

MA: Even if they just fall in love with the theatre! Theatre-goers and theatre connoisseurs can search for what appeals to them. They understand emotions. And for me, it makes them worthy of appreciation.

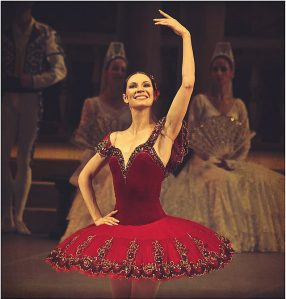

Maria Alexandrova performing at the Bolshoy Theatre.

VS: What are your professional plans?

MA: Earlier this year I left the Bolshoy Theatre and that was a very difficult decision to make. Nevertheless, I never stopped dancing. I am involved in many projects, have lots of invitations to perform. I am only starting to learn what it means to be a freelancer in this profession.

VS: Are you planning to move towards teaching?

MA: Not at the moment, but since I know the secrets of the profession, I feel it is my duty to share them with young generations of dancers. From time to time, I give workshops in Japan, and Japanese students love me a lot. The Japanese are a very pleasant and graceful nation. They are capable of learning. Maybe it is all again about those internal restrictions and frames…

We express our sincere gratitude to LRBS for their help in the publication of this interview.

This article originally appeared on Russian Art + Culture on September 29, 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Valeria Stračevská.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.