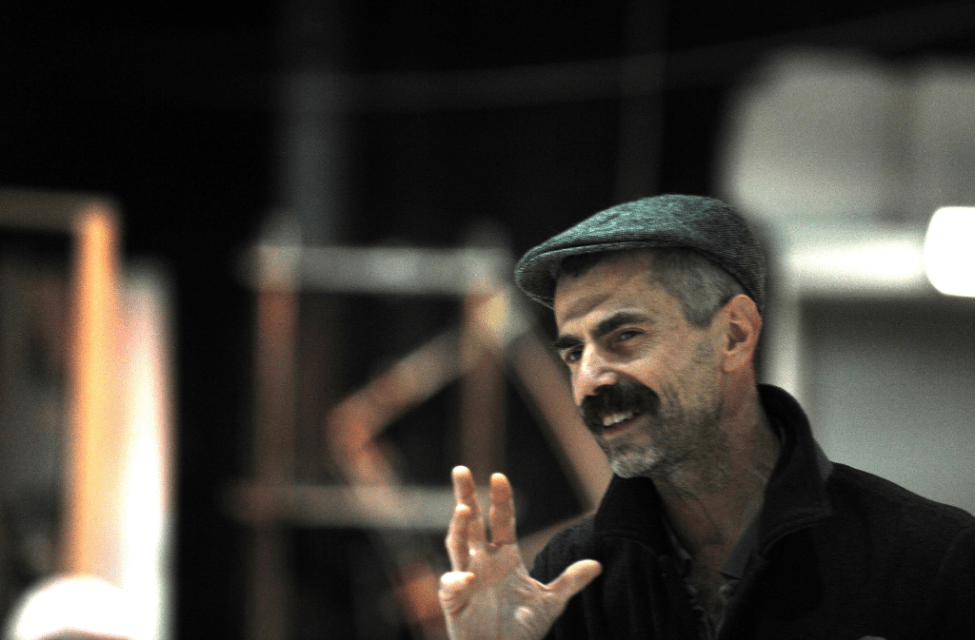

During the second edition of the artist-led Mercurio Festival in Palermo, the Italian choreographer Roberto Castello was invited to give a workshop and share his long-standing physical and movement experience with professional dancers, performers and actors. Considered as one of the pioneers that shaped the Italian contemporary dance scene, he is self-claiming to be the most politically engaged director and choreographer of his generation. Alone this statement is a strong invitation to explore the reasons behind this claim and it inevitably guided our discussion towards unraveling the political aspects of his work.

Il Migliore dei Mondi Possibili, UBU Award for Best Dance Theatre Piece (2003). Photo Credit: P. Rapalino.

Going back at the early stages of his career, Castello had collaborated as a dancer with Carolyn Carlson’s Teatro Danza La Fenice in Venice which he left in 1984 in order to co-found the Italian dance collective Sosta Palmizi and since 1995 he runs his partially state-subsidized dance company ALDES. One of his first works with ALDES was Siamo qui solo per i soldi [We are here only for money], a work that strongly criticized the politics of performing arts festivals and how poorly they compensated dance artists, especially the emerging ones; a problem that unfortunately persists today and shapes the mentality around dance and its value as labor. In 2003, he won the prestigious UBU award for his dance theatre piece Il Migliore dei Mondi Possibili, and approximately ten years later, he had the chance to collaborate with the British film director Peter Greenaway for the production of The Towers/Lucca Hubris (2013). Everyday gestures, dance, theatre, singing, and digital technology usually in the form of video projections constitute the tools that the moving body in Castello’s works employs or interacts with in order to offer to the audience a sensorial experience that narrates, often through irony, the reality and the mundane.

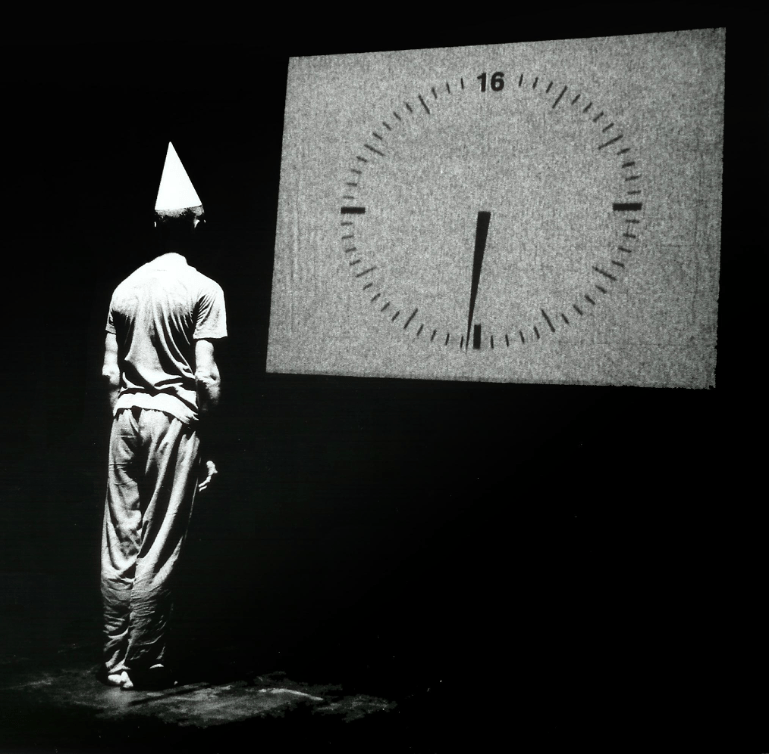

Castello was also the choreographer of Sfavillante that was commissioned by the national TV channel RAI3 as part of the four-episode program Vieni Via con Me (2010), a narrative of the contradictions of the Italian culture heard through the voices of well-known politicians, clerics, singers and musicians, actors and writers. The broadcast was a great success and each episode was viewed by approximately one-fourth of the Italian TV watchers. On that occasion, Castello created a choreographic work with vaudeville elements for seventeen contemporary dancers.

Sfavillante (2010) commissioned by the national TV channel RAI3. Photo Credit: Roby Schirer.

With his versatile background in mind, one of my first questions was concerned about the commercial or popular choices that he ever made as a dance performer and choreographer. Before answering this question, Castello clarifies that “it is important to keep in mind that Italy is a country where it is hard to survive as a dance artist due to the limited state support and lack of recognition of the dance profession”; two facts that were aggravated during the pandemic-related lockdown that saw the performing arts being characterized as non-essential activities. Referring to the income of the dance profession, he states that

You keep on asking yourself why doing this kind of work, if it makes sense to do what you do and if it is worth continuing in the same direction.

Beyond this self-debate, he confirms that “the answer is not being commercial and I refuse to take this direction in my work even though gaining an income from dance is extremely challenging.” “Nevertheless, I am still here,” which indicates that “there is a deeper motivation to maintain this profession after so many challenges.” Regarding popularity, he affirms that his work may be seen as popular only up to the degree that it aims to be communicative to those who wish to comprehend dance but they struggle.

At the beginning of his career as a dance performer and as part of the historic Italian dance collective Sosta Palmizi, he and his dance mates (a.o. Giorgio Rossi, Raffaella Giordano, Michele Abbondanza) opted to invest their energy in Italy and this is a decision that he still supports until today through selective choices that he considers anti-capitalistic. He refuses a lot of work offers and mainstream international festival invitations that oppose the “coherent path and chain of actions” that he constructs between what he is and what he would like to be as an individual and as part of society. Believing in the economy of exchange, he claims that

I am not interested in selling my skills to get a salary but in rewarding ways of exchange between providing skills and gaining an income through these skills.

Our discussion gradually shifts towards ethics and politics in relation to the practice of choreography and he states that

It is difficult to mark a line that separates the one from the other. I think that it is important to behave in the way you would like the others to behave, for instance in respect to unpaid work.

Castello was also one of the first Italian choreographers who experimented with digital technology and the choreographic potential it offers. In the late 90s-beginning 2000s, although having been very skeptical about technology, he humbly confesses that he was lucky enough to “be surrounded by artists who were very enthusiastic and keen to experiment with technology”. The outcome of this fortunate encounter was the creation of works such as Biosculture [1998], which was made with the choreographic software Lifeforms; Il fuoco, l’acqua, l’ombra [1998] in collaboration with Studio Azzurro and Le Avventure del Signor Quixana [1999] in collaboration with Paolo Atzori. Since 2005, he teaches the course Digital Choreography at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera in Milan. As he is both a choreographer and a teacher — although he insists on not being an educator — I was very much interested in hearing his opinion about the relationship of dance and technology during the pandemic, a period in which dance professionals used technology literally as a means of surviving.

He answers that

I do not think that technology helps in the evolution of dance. Technology is a tool in terms of how it facilitates everyday life but it cannot remove from dance its political value which is ultimately about sharing time and place with other human beings. The physical human presence is a fundamental political statement. Dance, physical contact, sweat, smell as concrete facts help us stay connected with reality.

Besides being a choreographer, Castello also runs the SPAM! project, a small choreographic ecosystem that has supported choreographers such as Francesca Foscarini, Giorgia Nardin, Marco D’Agostin, Ambra Senatore, Caterina Basso. Located in the countryside, SPAM! was conceived as a place to experiment with cultural politics and with strategies to connect with people and the local territory. His latest choreographic project — choreographic in the expanded sense — is the “93% materials for non-verbal politics”, an online space that collects writings by scholars and practitioners alike about the political potential of the body, the ways that dance practice interferes with the world and how the architecture of sense is built through dance. He states that

Our occidental culture and memory are based on writing. Dance critics and journalists, who bring attention to dance through words, often translate what they see, omitting to write about the process that shapes a choreographic work. This blog was created to bring more attention to dance and to appeal to people who do not understand movement as a language.

In a parallel attempt that aims to speak in a simple manner about theorized topics, Castello has written with Andrea Cosentino the book Trattato di Economia [A Treaty on Economy], a theatrical script that discusses the economy of desire and its relationship with money and the potential of the performing arts to create alternative economies.

Trattato di Economia on stage. Photo Credit: Elvio Caria.

Perceiving economy as a frame that influences human relations and life choices, a last question comes to mind that asks Castello for advice to the dance artists and workers who wish to earn their living from dance making. “Although we live in transitioning times and the future is unknown”, he suggests “to change your job. And if you really cannot change your job, try to find good reasons to keep on doing it.”

At the end of this enigmatic statement, I press stop and our discussion goes unregistered. We stand up from the small and noisy bar close to Cantieri Culturali alla Zisa and I walk side by side with this tall but grounded figure. His calm walking affirms confidence in dance to act as a social and moving structure of proximity and materiality that is capable of addressing current issues that matter.

Special thanks to Simona Argentieri, co-founder of Mercurio Festival and responsible for the dance sector of the festival, for organizing and enabling the meeting with Roberto Castello.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ariadne Mikou.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.