We are surrounded by violence and our country is beset by an ongoing cycle with little ebb and much flow. The search for a source, an attempt to extract some reason seems futile. On stage, we are presented with one of our origin stories, a glimpse at ourselves and the past and perhaps an inkling of how a nation raised in brutality continue to harvest the fruits. Die Reuk Van Appels is less of a lesson in nostalgia and more a remembering of a brutal personal and political past, so closely entwined as to make them indivisible.

An award-winning book that might never have seen the light of day, The Smell Of Apples was originally rejected by South African publishers and it was two years after the Afrikaans publication that the English version appeared to award-winning acclaim. Behr corrected both manuscripts simultaneously while studying in Norway, coincidentally the same country which saw the birth of Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country. Smith’s adaptation of the novel is a masterful feat. He hasn’t sacrificed the immediacy of the language or the page turning intensity for the stage. The script warps time as effectively as the book as we travel with Marnus between the war-torn region of Southern Angola and the battlefield of his St James home. Don’t be intimidated by the Afrikaans script if you aren’t fluent. The English surtitles ensure the piece is accessible and the riveting physical performance transcends language as you share a boyhood as banal as it was brutal.

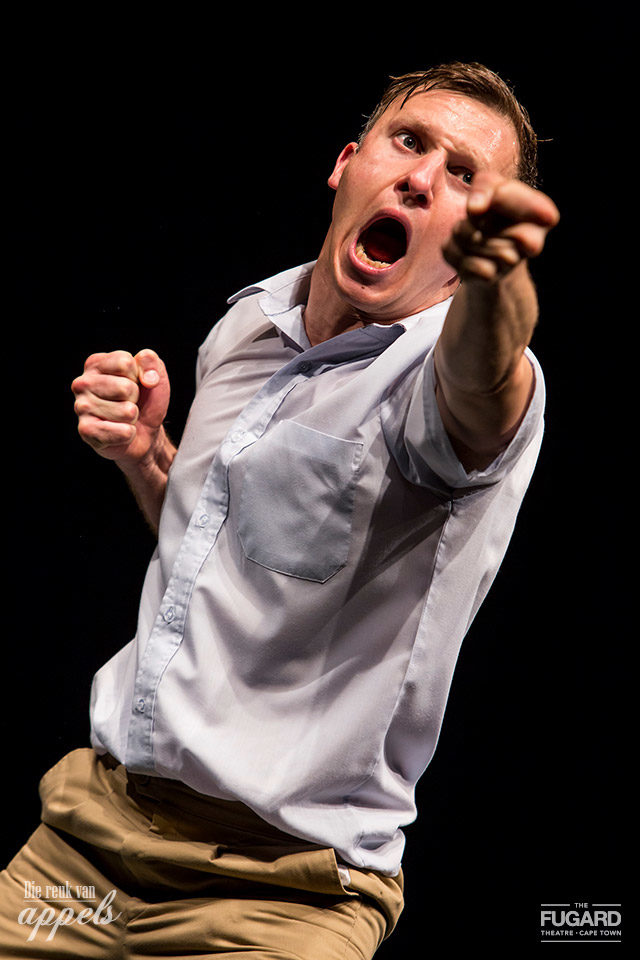

Press photo.

Lombard is Marnus, an eleven-year-old Afrikaans boy growing up along the False Bay Coast. It is not the coastline alone that subverts the truth. There is a fault line of deceit at the very core of his home. Marnus doesn’t merely reminisce about his childhood. He takes us with as he and his best friend Frikkie conquer tops at school, catch fish in the sea, marvel at the casts of the San in the museum and squirm at live bodies engaged in carnal activity in the nearby dunes. We share the cool, crashing exhilaration of waves with him as surely as we feel the sting of hot tears sting and wince at the burn of grazed knees. Lombard’s vulnerability as the young boy is mirrored in the innocent portrayal of Frikkie. He plays both characters with an endearing charm that will win your heart. Minutes later he is effortlessly a Chilean general, his Afrikaans mother, and his commanding father. He slips imperceptibly from one character to the next with a physical embodiment of the very essence of their characters that is incomprehensible, literally creating an entire cast out of nothing more than a pose, an inflection in the timbre of his voice. The subsequent shattering of his childhood psyche is so palpable that it is impossible not to physically flinch as each character meets his fate. Alongside the general childhood mishaps, his boyhood is the site of a far greater anguish.

Bye unfolds the narrative gently, with a naive humor, offering each layer of his life as a gift. It’s only when you have each and every piece delicately stacked one upon the other that the truth is revealed and the shuddering realization tears you to the core. The sketching of a privileged childhood lulls you into a sense of the commonplace and the ordinary but there is nothing ordinary about this life. His father, the youngest general in the South African Defence Force, his mother an international Opera singer and his country a cesspool of hatred and prejudice.

There is no attempt to whitewash the truth of apartheid. The evil is presented as is. Hearing the bigotry and cruelty articulated by a child is a harsh reminder of our history. Deep-seated, casual racism imbibed with mother’s milk, spooned up with the morning’s porridge and validated in the classroom lead to the killing fields of Angola.

Olfactory memories are often the most powerful, unsurprising given that we have at least a thousand receptors for smell and only four for sight. Marcel Proust, transported to his childhood memories by the aroma of a madeleine cookie in his novel ‘Remembrance of Things Past’ lends his name to the Proust phenomenon, the odor-evoked autobiographical memory which haunts Marnus years later and miles away. Lombard’s talents extend to a fine musical acumen and the soundscape drifts from frenzied military commands to strains of an operatic diva’s curtain call and the unforgettable voice of Esmé Euvrard, as she bolsters the morale of the troops on Springbok Radio’s Rendezvous. The intense recollection of the scent, the authenticity of the sound and Lombard’s riveting performance ensure that the swirl of dust unleashed by a helicopter catch the back of your throat, the spray from the crashing waves settles in your hair. While it is the smell of apples that disturbs his dreams, he leaves the audience with layer upon of layer of sensory emotions which settle deep into the marrow.

Bye has contracted the stage with a few square meters of artificial grass, setting very defined boundaries. Marnus is hemmed in, the strictures of his conservative family, the government imposed restrictions on freedom, the international boycott of the country is keenly felt. As the inevitable tragedy of his life becomes evident space seems even smaller, emphasized by Smit’s deft lighting. A chair, an army issue torch, and a wooden spinning top are the only objects with which he engages. He is overshadowed by the decorated general’s jacket, complete with epaulets – it hangs ominously, just out of Marnus’ line of sight but constantly present. A military authoritarian shadow hanging over his home and society, a private reminder of the public fear.

Behr’s public admission at a conference in Cape Town in 1996 to working as an agent of the apartheid government affords another retrospective lens with which to view the text. His birthplace in Arusha now stands opposite the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Ironical given that he was advised that his apartheid-era activity did not warrant testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Behr has written his truth, exposed a nation’s sins on the page.

Press photo.

“Thank you, forgive me. I kiss you, oh hands / Of my neglected, my disregarded / Homeland, my diffidence, family, friends.”

This is Boris Pasternak’s plea in the epigraph of the novel. In The Smell Of Apples, Behr offers the secrets of his family, his homeland, perhaps in a personal bid to expiate the past. While forgiveness remains an individual choice, forgetting as one leaves the theatre is not.

Die Reuk Van Appels runs at the Fugard Theatre in Cape Town from October 17 to November 11, 2017, with an age restriction of 16 (sex, nudity, strong language, violence, and prejudice). http://www.thefugard.com/

Written by Mark Behr and adapted for the stage by Johann Smith.

Directed by Lara Bye with Gideon Lombard.

Lighting design by Kosie Smit.

Sound design by Gideon Lombard.

This review was first published in Weekend Special on 23 October 2017. Reposted with permission

Tracey Saunders (Twitter @heartoftheatre) is a theatre critic, arts journalist, activist and the founding president of the South African chapter of the IATC.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tracey Saunders.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.