Anurupa Roy’s contemporary retelling of the epic uses a melange of cultural influences to focus on 14 characters.

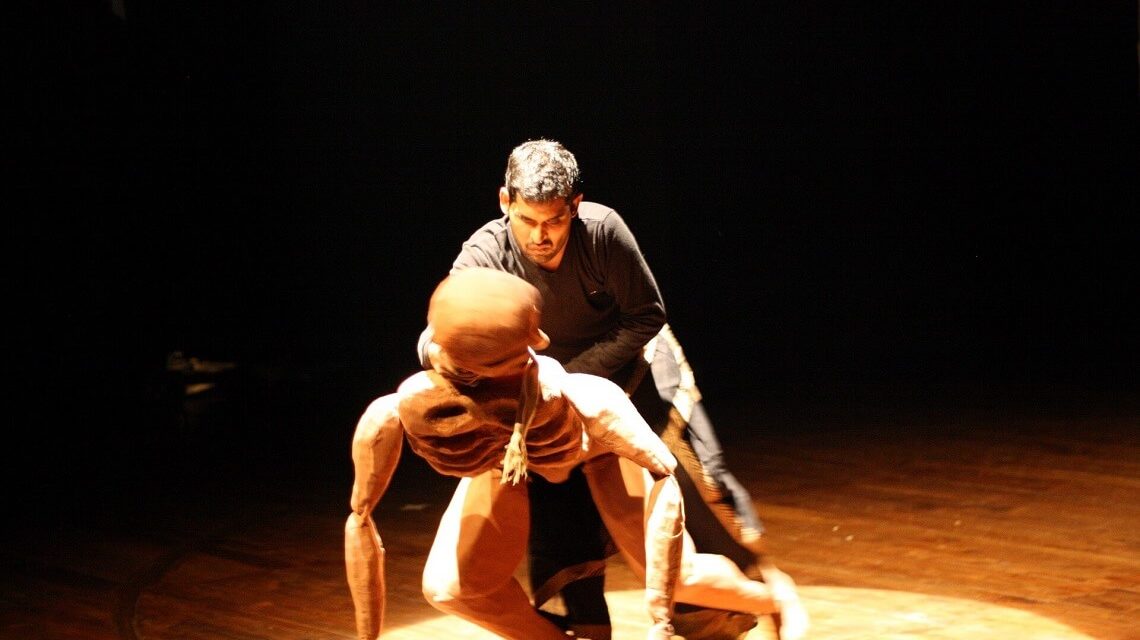

Mahabharata. Press Photo

Located on the banks of the winding river Meuse that flows northwards from France, the two historically distinct communes that make up the French town of Charleville Mézières were once connected only by a suspension bridge. Now conjoined, they share a common cultural identity. In late September, the town celebrated the 19th edition of its international puppetry festival—the Festival Mondial des Théâtres de Marionnettes, arguably the largest gathering of puppeteers from all five continents, which attracts an audience in excess of 150,000 people. Over the years, the town has acquired the reputation of being the World Capital of Puppetry Arts.

During the nine days of the festival (a biennial event since 2011), Charleville Mézières is transformed into a puppeteer’s paradise, with halls, gymnasiums, streets and squares, all commandeered into hosting superlative puppet acts and the ostensibly inanimate beings that populate them. One of the fixtures this year, from Spain’s Centre de Titelles de Lleida, featured a rambling Indian elephant, a single life-size puppet handled by three puppeteers. The itinerant show was quite appropriately titled Hathi, and its pachydermic protagonist trawled the city in majestic fashion accompanied by “Hindu music,” attracting captivated onlookers at each turn. Hathi brings to mind the recent Aasakta production, Gajab Kahani, which focused on an Indian elephant’s arduous trek across Europe circa 1551, as immortalized in José Saramago’s novel.

Another Indian attraction unfolded at a local basketball court — Heer Ke Waris, presented by the Ishara Puppet Theatre Trust. Directed by one of the flag-bearers of Indian puppetry, Dadi Pudumjee, the play drew from the classic 18th-century tale of Heer and Ranjha, as ascribed by Waris Shah, and presented a contemporary telling that interwove puppets, actors, masks, and movement. The festival itself supports a slew of international co-productions, and one of the beneficiaries has been the Katkatha Puppet Arts Trust. Under the aegis of this collaboration, they presented their bold new version of The Mahabharata, helmed by artistic director Anurupa Roy. The production employs the Japanese technique of Bunraku, masks and shadow theatre, elements of chau and kalaripayattu, and a melange of other influences to create a compressed interpretation of the epic with a focus on just 14 characters, and a running time of 70 minutes.

Eschewing the mainstream

Roy’s production opened last year in August at Ranga Shankara, Bengaluru, and has toured sporadically throughout the year, including a stint in France. It interestingly eschews the mainstream Ved Vyasa version of the epic, instead of drawing extensively from the oral traditions of the Togalu Gombeyaata, a form of shadow puppetry prevalent in Karnataka that employs puppets made of leather. Roy’s team was able to discover detailed stories obscured in the Vyasa manuscript. For instance, the plight of Subala, starved to death by Bhishma, provides us some rationale behind his son Shakuni’s diabolical plan for vengeance. His dice were made from the bones of his father’s right hand. Krishna is conspicuous by his absence—a choice the team continue to grapple with. Only his death due to Gandhari’s curse is foregrounded. “We wanted to emphasize the omnipotence of Krishna, and also dilute the idea that the war was between his friends and foes. The Mahabharata is a great leveler, and his absence makes him almost equal to the other fourteen characters,” says Roy. Balancing out both sides keeps the material resolutely in the gray, rather than the good-versus-evil crusade that the Great War is often represented as.

The canvas of The Mahabharata lent itself spectacularly to Roy’s form, although it took her team more than two years to improvise each character’s delineation. Two clowns stand in as masked vidushakas (or narrators), bridging the distance between the audience and the formal characters with repartee and sardonic insight. Amba appears in the battlefield as a magnificently bedecked bride, before transforming into the sinuous Shikhandi. Yudhishthira’s gambling addiction is a persona attached to him—a puppet with only a head and two hands. It effectively conveys the idea of a puppet manipulating the puppeteer, in the same way as an unhealthy predilection would exercise control on a hapless addict. Draupadi’s disrobing is illustrated with the pulling out of every strand of her puppet’s hair, which is significant because it is her hair that will be soaked in blood after the war, personifying that the war is really just a bloodbath.

The medium is the message

Because of its condensed format, and artistic selections, The Mahabharata has faced its share of detractors. After performances in Charleville Mézières, the production traveled to other French towns including Saint Germain-lès-Arpajon, a Parisian suburb. There, after a show, they were accosted by a woman affronted by the idea that the Bhagvad Gita had been completely excised from their rendition of the epic. She blamed them of kowtowing to Western tastes, a charge that Roy denies since the same version has been staged extensively in India as well.

Though her latest production is seen as a crossover success by those who pigeonhole puppetry into a reductive niche, Roy is refreshingly emphatic about how she would characterize her own work. “For me, the word is not theatre, it’s puppet theatre. The core of our work deals with the idea of the inanimate as an actor. We are not focused on the human body or human psychology, we are very aware that it is the inanimate that our audience watched and connects to. Sometimes we also happen to act with our puppets, but none of us are actors. We are puppeteers.”

The Mahabharata was performed at Nehru Auditorium, Worli on November 25

This post originally appeared in The Hindu on November 23, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.