The Kitchen, a one-hour, forty-minute play directed by Mohammad Hassan Ma’jooni, was staged in Tehran in November and December 2016. The original play was written by Arnold Wesker, the British dramatist, in 1959, presenting his socialist views and in the style of the kitchen-sink realism of the late 1950s and early 1960s. To bring the play home to Iranian audiences and free it from the London context and culture, Ma’jooni benefited from Mahdi Chakeri’s assistance as dramaturg. They worked on the play for about six months and brought many changes to different parts of it, such as the use of localized street slang, inserting some attitudes and actions belonging to the 2010s’ culture and today’s lifestyles, such as a worker’s filming of a quarrel in the kitchen. Another instance of such innovations is adding a new character to the original dramatis personae—the worker who plays the guitar on the stage and is called “the provider of the workers’ soul food.” Thirty-five actresses and actors performed in The Kitchen, most of whom were present on the stage in major parts of the play. The director, though, was quite successful in organizing and controlling this large crowd.

The play presents a day in the hectic kitchen of a crowded restaurant. It has two acts: the first happens at the time of serving lunch, the second, at dinner time. The two acts are separated by an interval. The first act begins with the nonstop comings and goings of the workers in the morning. A crowd of people—the chef, cooks, the butcher, waitresses, and other workers’ frantic working and walking, accompanied by their incessant talking and shouting, interrupted with fights and quarrels, tête-à-tête, the earsplitting noises of pots and pans—all create a chaotic and stressful workplace where workers struggle to accomplish their tasks amid competitions, jealousies, flirtations, and transient moments of sympathy. The kitchen is like a soup pot where all the ingredients are seething agitatedly and are in a continual boil.

The symphony of noises comes to a surprising halt in the interval between the two acts, when there is a break before dinner time. Here the noisy turmoil is replaced by peace and quietness. We see a more humane picture of the workers. A few of them staying in the kitchen have a friendly conversation and talk about their feelings and concerns. In this way, the action of the play moves from the outside world to the inside. The workers, fed up with the tedious work and inhumane conditions, complain about the restaurant owner’s exploiting them without paying the wages they deserve. All the workers are exhausted, desperate and dissatisfied with their working and family conditions. They make up a game in which they are supposed to tell the others about their dreams. At first it is difficult to remember, but when they do, it turns out that most of them already have what they fantasize about. The worker (Kevin) whose dream is a sound sleep falls asleep in the middle of the conversation; the one (Nicholas) whose fantasy is having a cool bottle of drink at hand any time he desires, pilfers it from the kitchen on and off; and the guy who dreams about silence already experiences it. They all desire to escape from the kitchen, but they appear not to have a better option. They fantasize about the world abroad, a utopia where working conditions are based on justice and humanity. As their conversation develops, we see the kitchen as a metaphor, a microcosm of a bigger world.

Almost all the workers are dissatisfied with their present condition. But they only complain and do not take any effective action to improve it. It is as if at the same time they unknowingly desire to keep their job and do not like to jeopardize the safety they have earned by leaving the place. In other words, the feeling the workers have for the kitchen is a love/hate one. This love/hate relationship can be sensed throughout the play, not only in the characters’ feelings toward their workplace but in how they treat each other. The subplot of Peter and Monique’s agitated relationship is an example of this love and hate. They are in a suspensefully desperate state as a result of Monique’s lack of willpower to divorce her husband, which creates a paralyzed condition that parallels the paralysis of the workers with respect to the kitchen.

The second act resumes the frenzy of dinner preparation and serving, while a heated argument starts among the workers. Peter, crazy with rage, starts breaking things, which turns the fight into a full-scale uproar. All the noise draws the restaurant owner to the kitchen to hush the workers. He has a monologue here that upends all our expectations about the owner’s attitude towards the workers. In fact, this is one of the significant changes that Ma’jooni and Shakeri have made in the content of the play. The audience sees a boss who has been well intentioned but not understood by his employees. He says he has tried to provide the workers welfare, and that they have always been free to come to work late or to take a leave or to pilfer things from the kitchen without being punished, and how ungrateful they have been. The workers only listen to him in shame and do not speak a word. This final scene shows that people in the kitchen are alienated not only from their work and workplace but also from each other, including their boss.

By changing the original final monologue by Wesker, which was in the service of his anti-capitalist thesis through presenting the restaurant owner as an unsympathetic capitalist employer, Ma’jooni inserts a new theme into the work; that is, that the kitchen is a microcosm of the city, the country, the world, or life, which we are always dissatisfied with. This could be regarded as a social critique by Ma’jooni, who is seemingly trying to change the attitude of people who always fantasize about a utopia—a dream that frequently results in dissatisfaction with and passivity toward our present conditions and the loss of possible chances of happiness and creativity we could have in our present life.

The Kitchen was on the stage in Pāliz, a nongovernmental venue in Tehran, from November 8 to December 23, 2016.

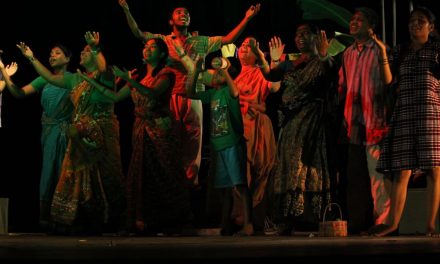

The Kitchen, directed by Mohammad Hassan Ma’jooni. Tehran Picture Agency. Photo credit Milad Beheshti

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Baharak Sahami.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.