Colm Tóibín’s play and the Booker-nominated novella The Testament of Mary aims to “demythologise” the story of Mary (the mother of Jesus). The play has toured globally and is now having its Australian premiere at the Sydney Theatre Company with Alison Whyte in the role of Mary.

Toibin’s is a moving portrait of a woman grieving her son’s death, with a distinctly modern feel. He undertakes an interesting literary experiment – though underlying this, his novella is littered with historical and theological claims that draw heavily on Christian literature.

Tóibín claims that Mary’s “real” story was repressed by the early disciples of Jesus. Though looked after by these disciples, Tóibín’s Mary distrusts them and resists their efforts to twist her story to suit their agendas. She struggles with the trauma of losing her son to what she sees as religious fanaticism. Ultimately, she rejects her Jewish faith and the idea that Jesus was the Son of God.

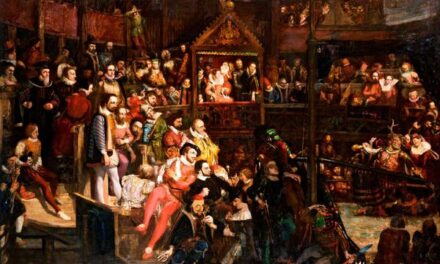

The play and the book it is based on have been much acclaimed for bravely challenging traditional beliefs about Mary. As the blurb on the Malthouse Theatre website puts it (the play will run there in November): “This Mary is unrecognisable from the meek, obedient woman of scripture, painting and sculpture.” But how plausible is this portrayal, from a historical, textual and theological perspective?

The historical context for Mary’s Life

There are various studies of first-century Palestine that give insight into the kind of life that Mary likely would have lived in small-town Galilee. Israel was then an agrarian economy with a small amount of commercial activity. Mary likely laboured for her household, was illiterate, and married at a young age, which meant entering into a large extended family.

Hers was a devoutly Jewish environment, permeating all aspects of life, with regular prayer, synagogue attendance, purity laws, temple worship, religious teachers and talk of miracles and signs. It was expected that God would act to restore Israel (through a Messiah) in opposition to foreign occupation.

Madonna of Humility by Fra Angelico, circa 1440. Photo Credit Wikimedia Commons

This contrasts with Tóibín’s Mary, who seems more like an educated modern skeptic. She is suspicious of cult-like behavior (on the part of Jesus and the disciples), anguished in her drawn-out introspection, and attracted to a glamorized view of “pagan” worship (neglectful of the violent and slavish aspects of it).

Tóibín’s account of Mary’s reaction to her son’s death is also problematic. While it has modern literary merit, it contrasts with the many Jewish mothers before and after Mary’s time whose sons (and daughters) lost their lives in Messianic movements, wars, and foreign occupations. These women did not forsake Judaism and label their family as fanatics (as Tóibín’s Mary does). This behavior would have been unusual at the time.

It is even more unusual in the context of what we know about Jesus, who led a broad-based, non-violent movement (far from a fanatical cult) that connected with contemporary Jewish expectations.

The textual evidence

There are various textual sources and traditions about Mary, both Christian and Islamic. The oldest are the writings of the Christian New Testament from the first century. These likely emerged from various early Christian communities.

The four Gospels (a major part of the New Testament) are the closest written accounts of Mary’s life. Tóibín draws on these sources for his own telling – re-interpreting key stories according to his narrative agenda.

Tóibín primarily draws on stories about Jesus and Mary that are recounted in the Gospel of John (such as the wedding at Cana and raising of Lazarus). Yet the theology of the Cross to which Tóibín seems closest is drawn from the Gospel of Mark.

Mark’s account of Jesus’ death focuses more on Jesus’ suffering and the loss experienced. John, however, presents Jesus as triumphant and kingly. This mixing of Gospel stories and approaches is typical of historical reconstructions, but it is avoided by scholars because it takes the stories out of their narrative context and betrays a misunderstanding of their genre and theology.

A shrine to Mary: is it plausible that she would have forsaken her Jewish roots after Jesus’s death? Photo Credit Shutterstock

Moreover, in contrast to Tóibín’s approach, the New Testament largely presents Mary as a supporter of the Jesus (or Christian) movement. Scholars have little reason or evidence to question such an account. In fact, some scholars suggest there was a prominent role for female leadership in the early church.

The Gospels contain indications that Mary (or those close to her) may have even confided information about her experiences of Jesus to early Christian communities (though this is difficult to fully determine).

There are stories in the Gospel of Luke from Mary’s perspective, such as the Annunciation of Jesus’ birth, Mary’s visit to Elizabeth (the mother of John the Baptist), the Presentation of Jesus, and an episode when Jesus goes missing at 12 years old. After the latter episode, the Gospel of Luke recounts Mary’s initial confusion:

But they did not understand what he [Jesus] said to them. He went down with them [Mary and Joseph] and came to Nazareth, and was obedient to them; and his mother kept all these things in her heart. (Luke 2:50-1).

Luke portrays Mary as not always understanding what happens to Jesus, but also shows her as a faithful Jewish woman who believed the Messiah had come in Jesus (even after he had died).

Toibin with his novella in 2013. Photo Credit Olivia Harris/Reuters

The Gospel of Mark also expresses the concerns that Mary and Jesus’ family had about Jesus. There is one story in Mark (3:20-35) that involves them trying to bring Jesus home from his public ministry, prompted by false reports that he was possessed.

If the disciples had, in fact, repressed Mary’s testimony and wanted to present Jesus’ family as wholeheartedly supportive of his religious mission (in the conspiratorial fashion that Tóibín presents), why would Mark or Luke include stories that show the family’s doubts? Surely, the early disciples would have just re-written these stories to suit their agenda, as Tóibín claims John, Peter and the other disciples did.

Assessing Tóibín’s Mary

Both Tóibín and the New Testament use narrative to weave a theological story. The Christian sources, though, seem to have more historical and theological plausibility than Tóibín’s account, and may even directly reflect Mary’s own attitudes.

While Tóibín’s story arc of Mary forsaking her Jewish roots and her own son’s teachings after his traumatic death may seem plausible to a modern reader, it is improbable historically, textually and theologically.

The most likely historical scenario based on the evidence – to which most scholars seem to subscribe – is this: Mary accompanied her son during his life (at least at key moments) and was a member of the early Christian movement.

Mary seems to have professed belief that God’s promises to the poor and oppressed were fulfilled in her son (as Luke recounts). She was likely cared for by the Christian movement after Jesus’ death, but not under the cloud of conspiracy and coercion that Tóibín portrays.

Historical recreations can often tell us more about the author than the subject. The Testament of Mary is an interesting literary experiment, exploring the depths of grief and warning about the dangers of modern religiosity. But any parallels to history or religious belief should be greeted with proper scepticism.

The Testament of Mary is at the Sydney Theatre Company from 19 January to 25 February.

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Joel Hodge.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.