The stage adaptation of Léonora Miano’s Ce qu’il faut dire (or “What Must be Said”) addresses a longstanding taboo in French society around the open discussion of race. A central tenet of contemporary French republicanism, alongside the country’s frequently debated version of secularism, or laïcitié, is the principle of “colorblindness” between individuals and the state. In its attempts to discard what is seen as the false categories of racial identity, the state actively suppresses the acknowledgment of race at any official level. Thus, in France, where the state is deeply involved in funding and promoting theater and culture, it is difficult, or at least controversial, to speak explicitly of a “Black” French theater as one might evoke Black American or British stage performance. At least part of this difficulty stems from a problem that is not at all specific to France, which is the simple lack of representation of racialized artists in the world of the contemporary arts; this relative absence has been highlighted and criticized most notably by a recently founded and expanding “Decolonizing the arts” movement. But there is also an official refusal, at least on the part of public entities, and often on the part of individuals, to recognize that, even in a purportedly colorblind context in which the vocabulary of race is eliminated, racialization remains an ever-present reality in the lives of many of the country’s citizens.

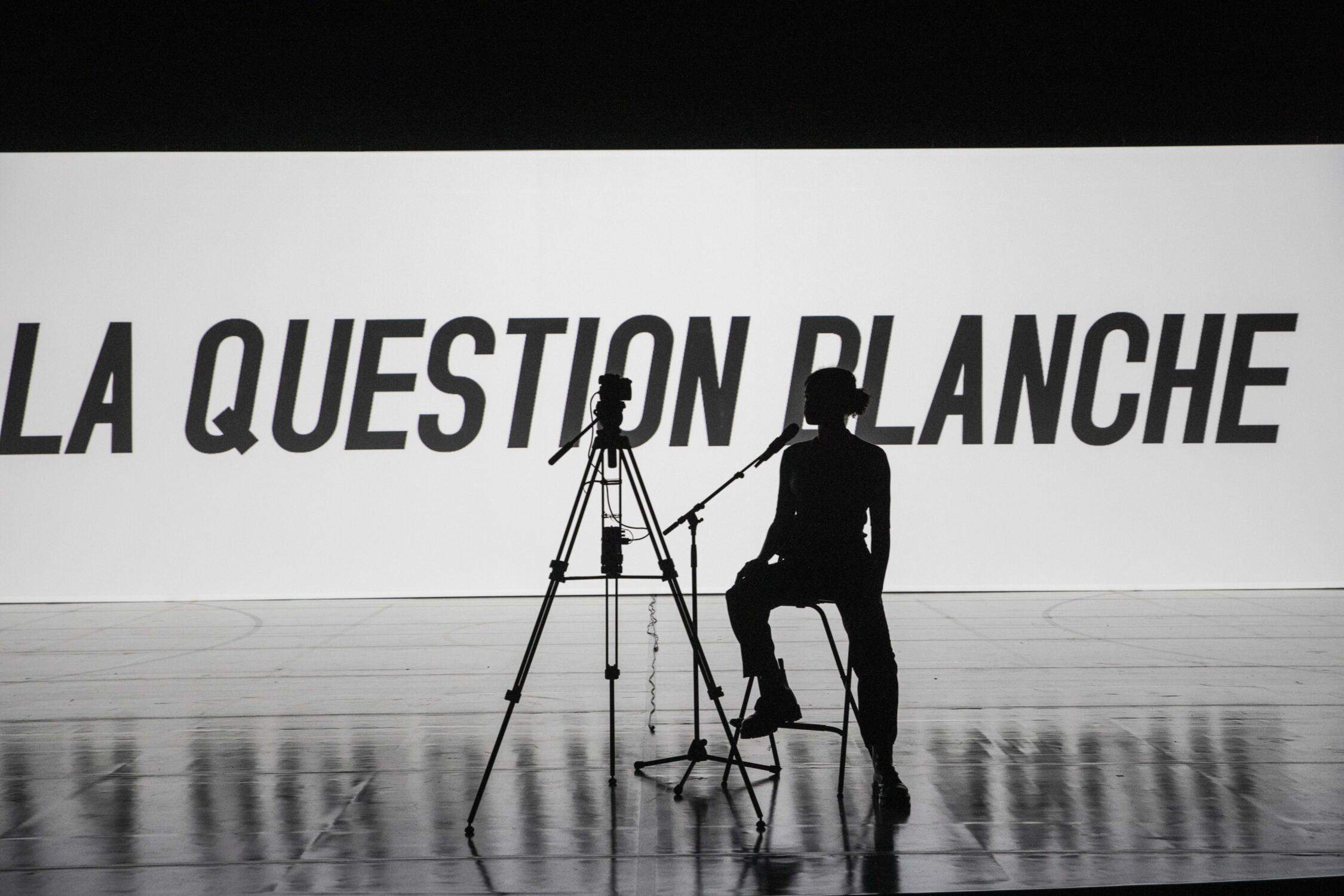

The first section of Miano’s text, entitled “La Question Blanche,” examines such processes of racialization by addressing their starting point in the white gaze. Miano’s poetic essay, which was published as part of a collection called “Des écrits pour la parole” (L’Arche), is composed of texts that the author first read during spoken-word recitals. The text opens, provocatively for a French audience, with the voice of an unnamed but already racialized female narrator, who asks: “Why are you afraid / Of what / It’s you who brought us here / Dragged us down this slippery road This slope / It’s you who said / Black Woman.” The direct address to the presumed-to-be-white reader/listener, on whose part a certain amount of trepidation is expected, breaks the silence around race imposed by republican bienséance. Pointedly, Miano also ties the history of racial identities, and specifically Black identity in France, to a transatlantic past that extends beyond the temporal and geographic limits of French republicanism. In this, her approach aligns with that of the French-Ivorian scholar Maboula Soumahoro who, in her essay on race in France, Le Triangle et l’Hexagone: Réflexions sur une identité noire (“The Triangle and the Hexagon, Thoughts on a Black identity,” 2020), states her own subject position by declaring defiantly, in a gesture which she calls a “coming out,” that “my ‘I’ is that of a black woman developing for the most part between the Hexagon and other lands of the Atlantic Triangle.” Both authors thereby affirm that such transatlantic histories cannot be eradicated by the mere absence of race from the vocabulary of “colorblind” republicanism.

Photo Credits: Jean Louise Fernandez

If Miano’s published text considers racialization in the absence of a body to racialize, in his staging, the French director Stanislas Nordey uses the embodied techniques of the theater to call attention to the audience’s collective and unspoken recognition of his actor’s Black French identity, and this despite the refusal of French institutions to recognize blackness in any official capacity. In Nordey’s staging, the actor Ysanis Padonou sits on a stool and speaks directly into the camera’s lens that is placed about one meter to her right; the filmed close-up is live-streamed on a large screen that stands just behind her. As Padonou speaks, the spectator’s gaze is deprived of a stable object of focus. The live body, which we recognize as black (and thus racialize), does not return our gaze, while the filmed image that hovers above the actress, stares directly at us. The multi-perspective staging, combined with Miano’s frank discussion of race, produces an embodied awareness of, and defamiliarization with, racialization, and especially the role of the white gaze in the formation of racialized identities.

Nordey’s stage effect is not, on its own, new; the defiant returning of the objectifying white gaze in his production might even recall for some the international stir caused by the South African director Brett Bailey’s controversial piece Exhibit B. In Bailey’s production, Black actors recreated, through a series of living tableaus, the spirit of the European human zoos of the nineteenth century, all the while staring back at the spectators who have been invited to gaze at them. Exhibit B and the wave of contestation that greeted its French tour proved instrumental in catalyzing what would become the “Decolonize the Arts” movement in France. Nordey has also been the target of criticism from the same movement over the creation of a training program designed for minority actors in France called Ier Acte (“First Act”). This program has led activists to object to what they see as an implication that racialized artists require supplemental training; they argue instead that the primary obstacle to their professionalization is their persistent marginalization within the majority white cultural industry. The two white stage directors, Bailey and Nordey, clearly share, in their treatment of anti-black racialization, an interest in highlighting the perniciousness of the white gaze; however, Nordey’s approach differs significantly from Bailey’s in that his production does not reenact transatlantic histories of anti-black oppression. The racialized subject is not put on display but rather speaks eloquently, poignantly, and even tauntingly at times to the majority white audience that is her interlocutor.

This is perhaps one of the most striking characteristics of Miano’s writing and one that is successfully captured in Nordey’s stage adaptation. While adept at exploring complex racial dynamics that lead to both micro-aggressions and larger systems of oppression, the author’s work does not make appeals, even indirect ones, to the pity, approval, or indignation of her white readers or audience members. Her narrator in “La Question Blanche” addresses the reader by the informal singular French pronoun “tu,” installing a sense of familiarity, intimacy even, and above all equality that gives way to a certain righteous dismissiveness when, at the section’s end the narrator concludes: “So We won’t speak to Each other Is that it / You won’t Answer the white question will you” and finally: “That’s fine / Me / I’m not afraid / of the dark” (in French, the word for dark is “noir,” or literally “black”). At this point in Nordey’s staging, the lights have come up completely on the house, and we can no longer see the actor, who is hidden in obscurity.

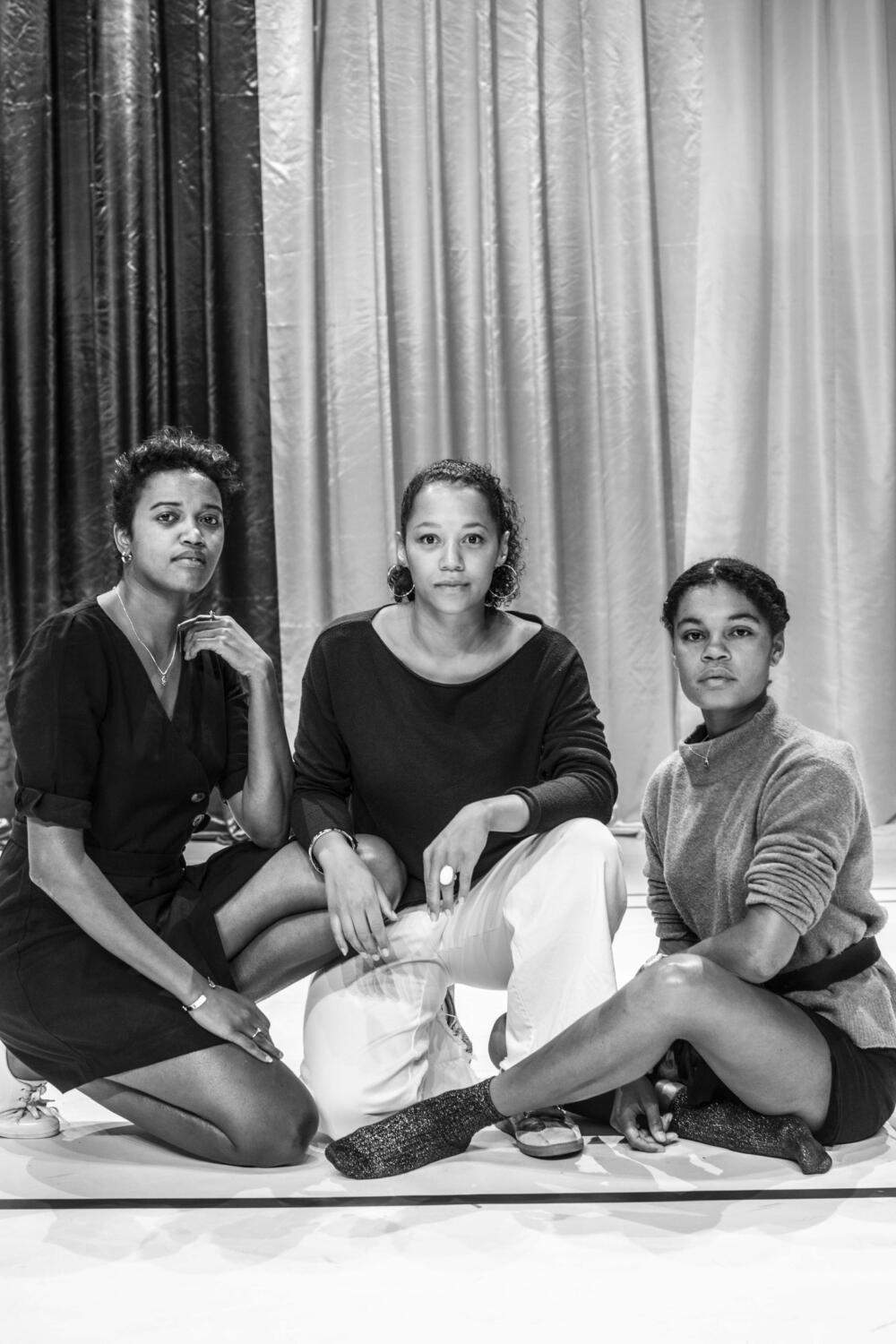

Oceane Cairaty, Melody Pini, Ysanis Padonou. Photo Credits: Jean Louis Fernandez

Miano’s main target in this dialogue on racialization is not the black identity which has been assigned to her narrator; it is the far less examined category of whiteness, depicted here as a delusion long perpetuated by mainstream white society in part through its representations of black bodies. In the stage adaptation, the informal singular second-person pronoun “tu” that is used to address collectively the (typically majority white) theatre audience reflects the dialectical interdependency of black and white identities. It instates a productive ambiguity as to whether the text’s assumed addressee is collective or singular. The viewer, especially the white viewer, may easily have the impression of being the intended “tu” in question; however, the text’s content suggests a more collective addressee. This allows the text in performance to inhabit an undefined space in between the collective and individual registers. It interpolates an imagined addressee who is just as impersonalized as the narrator, thus avoiding an unproductive attempt at eliciting overwhelming personal guilt or horror (as might be provoked by Bailey’s Exhibit B), while preventing a dissipation of responsibility into a broader, scarcely interrogated collective whiteness, two extremes that might preclude any real, personal reckoning with “La Question Blanche.”

The stage production includes two additional and equally compelling sections, the second of which, titled “Le fond des choses” (The bottom of things), speaks more specifically to the realities of race within a French context. In one notable passage, the text and performance calls into question the frequent use in contemporary France of the term “Français de souche,” which employs a biological vocabulary (de souche meaning of the original source or root) to signify white French. Miano’s text forcefully drums upon the contradiction inherent in a society that refuses to employ the term race but takes recourse, in popular usage, in the language of biology to refer to those French who are not marked by the racialization associated with the country’s colonial past. In Nordey’s stage version, the actor Mélody Pini, accompanied by a percussionist, declaims rhythmically, as if to ingrain the phrase in the memory of audience members, that “To Say Français de souche Is to affirm that A French race exists / To Say Français de souche Is to affirm the purity of French blood.”

A third and final section, called “La Fin des Fins,” (“The End of Ends”) and performed by Océane Cairaty, enacts a meaningful shift in the work’s discourse. The spoken text is no longer addressed to the audience qua audience but rather to an absent addressee, who is a similarly racialized Black woman, to whom the narrator rehearses a plea that she plans to make that evening to a male acquaintance. The man, Maka, has recently recounted to her a dream in which the histories of African heroes and liberators are commemorated by street names and monuments. Upon awakening, he lands on a somber assessment of the future for the racialized citizens of France: “I opened my eyes here, dismissed the dream and, once more, cloaked myself in silence. Here is not and never will be our home.” The narrator plans to entreat him: “Imagine, Maka, if we were to take History by the other end. That is, by the end that doesn’t finish with pain but with overcoming it. Imagine. Tell yourself that pain is the starting point but not the destination and that it is precisely between the two that History has unfurled. Do not think of yourself, of us, Maka, in terms of the injuries imposed.” The vision described by the narrator, far from constituting a retreat into essentialist racial categories, invites the listener, along with Maka, to reinvent a collective relationship to history and the racialized categories that have resulted from it. Whether or not we, the reader or spectator, see ourselves in the “we” uttered by this third narrator will depend on our position within the processes of racialization. One strength of the text is that it invites a reimagining of collective history primarily among and between racialized communities without seeking the approval or complicity of a hegemonic white culture. Miano’s work deploys the author’s own decolonial tactic by examining and naming, from the position of the racialized subject, the processes, and consequences of centuries of racialization; it then proposes a vision by which racialized communities might take possession of History and find a way to make a home for themselves within the strictures and ideals of today’s republican France.

Brian Valente-Quinn is a professor of Francophone African Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. He writes and researches extensively on Francophone theater and performance with a special focus on the intersection of French-language stage culture with contemporary issues such as immigration, extremism, and decoloniality.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Brian Valente-Quinn.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.