KPOP is a new musical, with a book by Jason Kim and music by Helen Park and Max Vernon. It premiered at A.R.T./New York as a co-production by ArsNova, Woodshed Collective, and Ma-Yi Theater Company in 2017, and recently opened at Circle in the Square on Broadway on November 27, 2022. The musical centers on and is infused with K-pop, a genre of Korean contemporary popular music, which is a hybrid of various genres including EDM, hip-hop, R&B, rock, dubstep, and pop, optimized for stunning choreography in live performance, and oftentimes mix Korean and English language in the lyrics. K-pop has recently become a global leader in contemporary popular music and the center of hallyu (the Korean cultural wave), with the worldwide success of K-pop artists including Psy, BTS, Blackpink, NCT, SuperM, TWICE, and Seventeen.

In the musical, RBY Entertainment, a fictional Korean entertainment company, is preparing its New York showcase, called “RBY Live,” which is happening the next day. The company is set to debut two new groups RTMIS (pronounced Artemis), a five-member multinational girl group, and F8 (pronounced Fate), an eight-member boy group. The showcase will also feature the company’s star entertainer MwE (pronounced Mu-wee), who is portrayed by the real-life K-pop superstar Luna. Other characters include the documentary film maker Harry (Aubie Merrylees), who positions himself throughout the set and action, to capture intriguing footage for the concert documentary he is creating, and RBY’s CEO Ruby (Jully Lee), who tries to make sure everything is set in place for the next day’s showcase. KPOP marks a historic achievement, being the first Broadway production with a mostly Asian creative team and cast. It is further distinguished by the fact that it tells a distinctly Korean story with its groundbreaking creative team and cast.

My trip to New York City to see KPOP was rather abruptly planned. The producers made a sudden announcement that the production would be closing on December 11, 2022, after only a two-week run. This action forced me to change my ticket, which had been purchased for a later date, and make a trip to see the closing performance. For this article, I am focusing on the artistry of the production and the cultural context in which it exists and to which it contributes – that is, how K-pop is reflected in this musical and how the musical uses the K-pop genre forms to tell a story. A brief discussion pertaining to KPOP’s abruptly announced closing will be provided at the end of the article.

This article seeks to archive in written, descriptive form the production in its time and place. I believe I can offer a unique and valuable perspective as a South Korean theatre artist; as a critic who wrote about the original 2017 production and interviewed members of the artistic team in two articles in The Theatre Times – “The ‘KPOP’ Invasion in a New American Musical Part I” and “The ‘KPOP’ Invasion in a New American Musical Part II: Interview with Jason Kim and Helen Park”; and as a fan of K-pop who saw the birth, rise, and evolution of the music since the early 1990s in Korea and its subsequent rapid growth in international popularity.

Poster Outside of Circle in the Square, Introducing F8. Photo Credit: Walter Byongsok Chon

I would describe my overall experience of KPOP as a feast of heung, a distinctively Korean emotional state, which Professor Suk-Young Kim translates as “spontaneous energy stemming from excitation, inspiration, play, and frolicking” in her book K-Pop Live: Fans, Idols, and Multimedia Performance.[i] Kim attributes K-pop’s global fandom to its unique kind of “liveness” that generates heung and transcends cultural, medial, and national borders in its appeal to fans. In this musical, heung is built through many skillfully combined elements. First is the music, which reflects an authentic variety of popular K-pop sounds and subgenres. Second are the musical performances, both solo and ensemble, which demonstrate versatility and meticulous precision in their choreography. And third are the classic and widely appealing themes regarding overcoming challenges, reaching maturity, and forming deep bonds through the process.

For K-pop fans, KPOP would have been all the more exciting – for the chance to see K-pop song and dance live, in a musical form – and also might have rung a familiar bell for its similarities with the real K-pop scene. The casting of Luna as the superstar MwE raised high expectations on its own, as her role reflected her life as a member of the popular K-pop group f(x), which, since their debut in 2009, garnered global fandom with hits such as LA chA TA, NU ABO, Hot Summer, Red Light, and 4 Walls. The character MwE is also strongly reminiscent of the K-pop superstar BoA, for the use of capital letters bracketing the three-letter name, her rise to stardom in her teens after years of grueling, systematic training, and the backing of a mega entertainment agency. (Luna and BoA were label mates in SM Entertainment until Luna’s departure in 2019.) KPOP’s framing device – the making of a concert documentary, featuring and promoting multiple artists from a mega entertainment agency – brought to mind SM Entertainment’s concert documentary film I AM (2012, directed by Choi Jin-sung). This film documents the rehearsals, backstage scenes, interviews, and concert footages of SM Entertainment’s artists, collectively called SM Town, for their 2011 live world tour in Madison Square Garden and features both BoA and Luna.

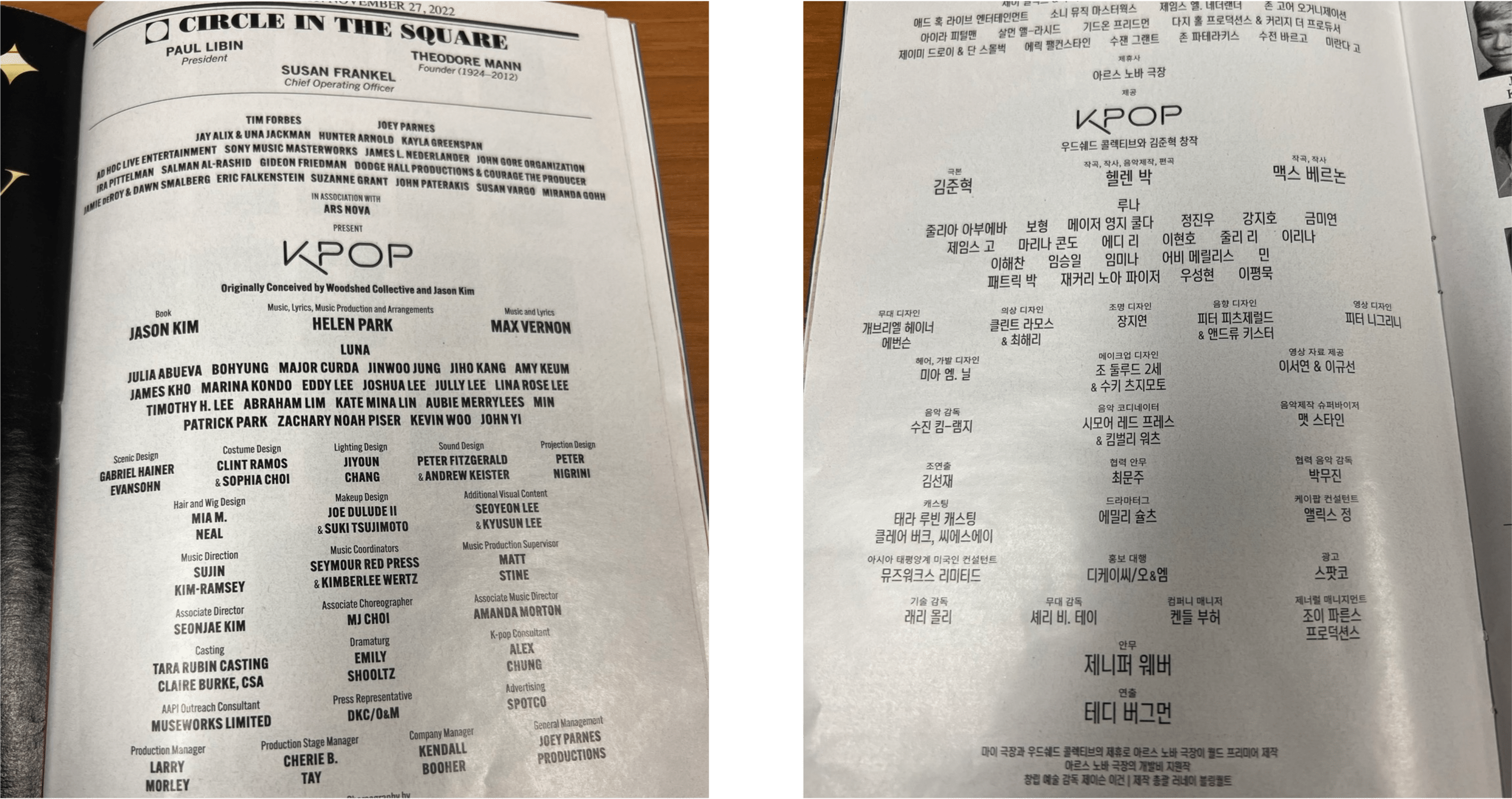

Credits, in Both English and Korean. Photo Credit: Walter Byongsok Chon

Stepping into the Circle in the Square Theatre felt like entering a club, with multiple screens promoting the hot debut of RBY Entertainment’s new groups with meticulously designed promotional images, thumping music, and spotlights highlighting the thrust stage. The audience was already in a party mode, freely taking selfies with the stage and screens and even dancing. While the audience included an eclectic demographic of multiple ethnicities and ages, also parents with their teenage children, at the same time it was refreshing to see such a huge auditorium filled with a majority Asian audience. The credits in the program handout also embraces and advocates multi-nationality, as the creative team credits and the musical numbers are written in both English and Korean.

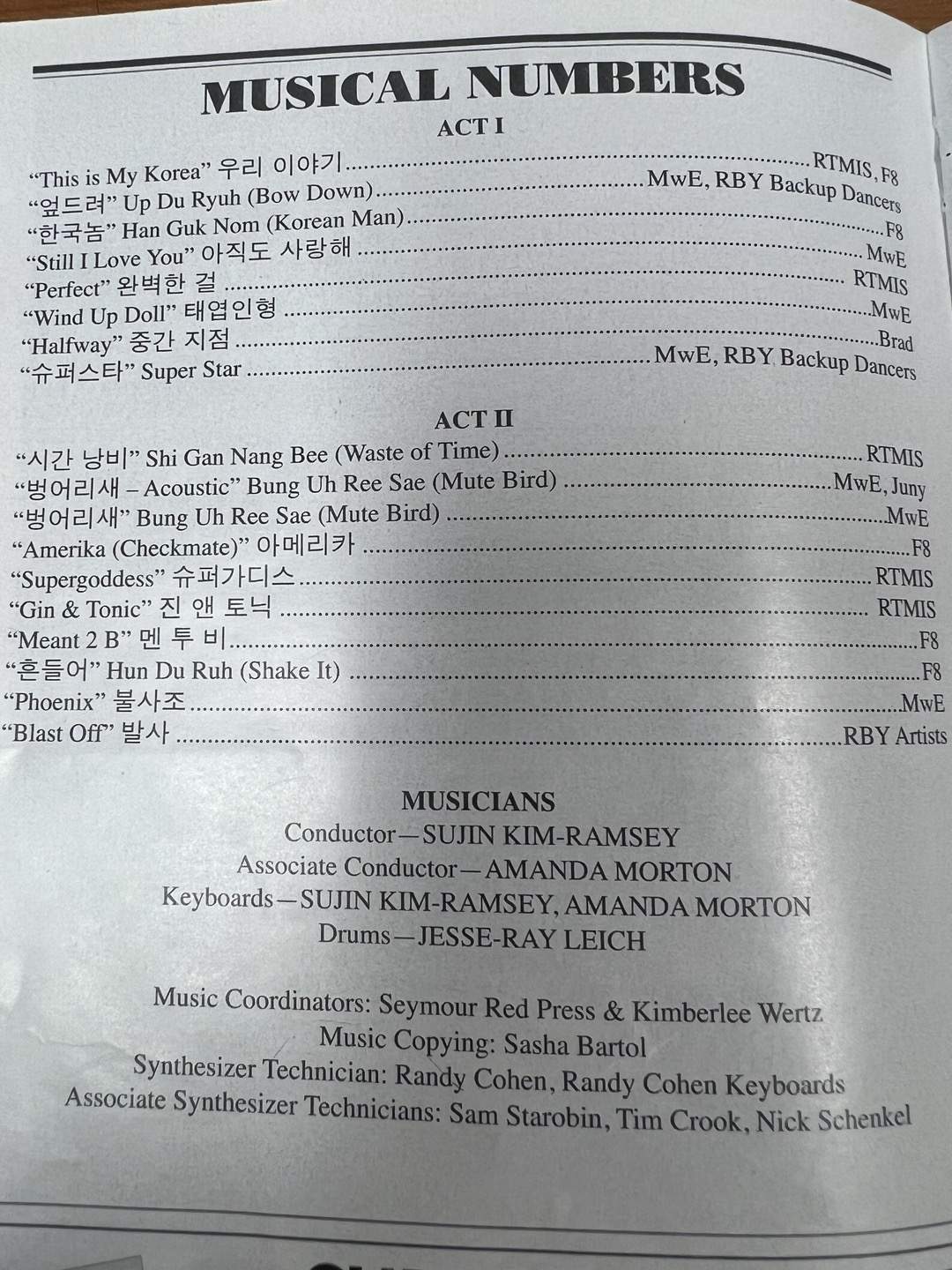

Musical Numbers, in Both English and Korean. Photo Credit: Walter Byongsok Chon

The musical numbers adroitly reflect the popular sound that has come to be recognized as K-pop. The opening song “This is My Korea” by both RTMIS and F8 is already a blast, an upbeat song with uplifting lyrics, colorful costume, meticulously synchronized choreography, and catchy chorus – “This is my Korea, this is my story-ya, new territory-ya” – that invites the audience to sing along and gets them moving. Even though RTMIS and F8 are new groups in this world, their singing and dancing, their fluency in performing for the camera and for the audience, and their charisma make it clear that they are ready for superstardom. The audience is already in love with them.

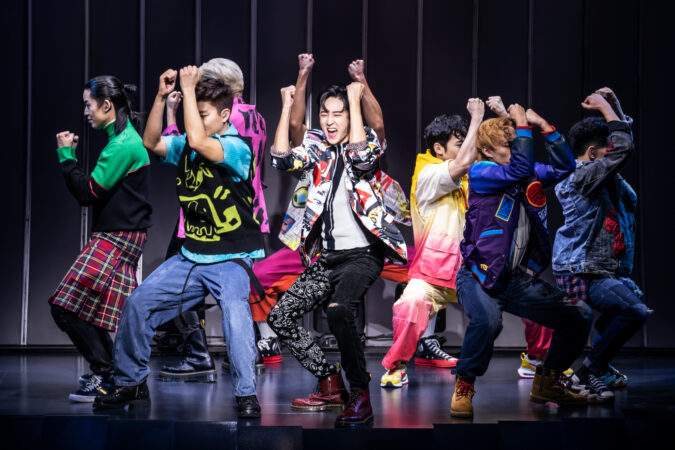

The Cast of KPOP. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy

The musical numbers brought to mind some iconic K-pop performances. For example, MwE and RBY’s “Up Du Ryuh (Bow Down),” a song with strong EDM and dubstep sounds, where MwE is dressed as an ancient princess, reminded me of Lee Jung Hyun, who rose to superstardom with her techno music, captivating stage presence, and lavish, evocative costumes, which gave her the nickname “The Techno Warrior” in the late 1990s. F8’s “Amerika (Checkmate),” a mixture of hip hop and EDM, showcased the group’s synchronized kinetic dance moves, which was reminiscent of the original lineup of TVXQ, a formerly five-member boy band that ruled the K-pop scene with songs including “Rising Sun” and “Mirotic” in the 2000s. The pairing of RTMIS’s two songs “Supergoddess” and “Gin & Tonic,” one with an edgy and heavy sound and dark tone and the other light and bright, reminded me of the debut of H.O.T. (Highfive Of Teenagers), a five-member boy band from SM Entertainment from the 90s. At their debut, H.O.T. conquered the K-pop scene with two drastically different songs – “Warrior’s Descendant,” a gangster rap criticizing school violence, and “Candy,” a light and colorful dance number about a naïve love confession. The contrast showcased H.O.T.’s broad expressive range in genres, tones, and performances, and cemented them as a leader of the so-called “First-Generation K-pop Idols.” Connecting these dots gave me both comfort and excitement.

The Cast of KPOP. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy

While the kinetic performances and the rich eclectic soundscape characterize many of the songs in KPOP, there are also songs that highlight the performers’ vocal caliber and emotional range. F8 member Brad (Zachary Noah Piser), a late addition to the group, was recruited from the US for “the American takeover,” and his solo acoustic ballad “Halfway” poignantly conveys his emotional vulnerability. Both F8 and RTMIS show their vocal harmony and group synergy through their respective a cappella songs. (These numbers brought to mind SM Entertainment’s groups TVXQ and The Grace, both of which were promoted as a cappella groups upon their debuts.)

MwE gets to display the widest ranges of vocal and performance as well as emotional journey, as KPOP centers her story, from her discovery by Ruby, through the rigorous training, and to reaching super stardom. As she rehearses for the concert the next day, MwE goes through the stages of her life, starting with her audition eighteen years ago, and has to face her demons, dealing with the abandonment by her mother at an early age, her search for self amidst being a superstar, her fear of being replaced by the up and coming stars, her romance with her guitar instructor, and taking charge of her artistry and her future.

Witnessing MwE’s growth through each stage of her life is both uplifting, as we see her hard work and sacrifice pay off in her success, and, at the same time, somber, for the pains she has had to endure from such a young age. Her songs reflect who she is at each stage. She is a “Wind Up Doll” early in her career, as she confesses her commitment to her love with an upbeat teen pop song. A few years later, she is a “Super Star,” demonstrating her maturation in a sexy, edgy, and seductive rock number which includes an energetic dance break. As she gets ready for the New York concert, she feels like a “Mute Bird,” as she confronts the pain of losing her mother and her inability to express what she really wants to in a self-written poignant and reflective ballad, which is sung both acoustic and as a power ballad with a full band. In the present, she rises like a “Phoenix,” overcoming the challenges in this anthem about empowerment, belting out like a queen: “I’m gonna rise so high, cause I’m feeling so alive. It’s time to break away, just like a phoenix I’m reborn from the decay. Now I’m here to stay.” Seeing MwE growing right in front of us, as an individual and an artist, feels both intimate, as her journey is so personal, and epic, for the broad spectrum of emotions as well as musical and performance ranges she displays.

Luna in KPOP. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy

Around the story of MwE, other dramas ensue. F8 has an internal conflict between Brad and the rest of the group. The tension escalates through the documentary director Harry’s scheming, as he considers the conflict great material for the documentary. Members of RTMIS have to overcome their differences and find harmony with each other, both musically and personally. Ruby has multiple tasks. She has to take care of MwE’s crises for the concert and guide her in the right direction, make sure that her new artists are prepared for their debuts, and fend off Harry’s disruptive attempts. The various plotlines well convey the tense atmosphere behind the scenes on D-1 to the big day and provide narrative balance around MwE’s central story. Additionally, Ruby’s question to Brad “When we do this tomorrow, will the audience be seated already?” had a poignant and metatheatrical ring to it, considering this performance of KPOP was the closing performance.

The concept of making the whole space like a club, under Teddy Bergman’s direction, works optimally to immerse and excite the audience through the show. The thrust stage, designed by Gabriel Hainer Evansohn, is set up like a dance stage in a club, around which audience members cheer for and dance with the performers. Seeing the excited audience members made me feel like we were invited guests, watching an exclusive concert. The party escalates gradually, with the exhilarating musical numbers, fully loaded with sensory stimulants that invite the audience to let go of their inhibition and the conventional decorum of sitting still and quietly. The costumes, by Clint Ramos and Sophia Choi, frequently change by each musical number and enhance the color plate, sometimes unifying each group as a collective and sometimes highlighting the distinctive character of each performer. Jiyoun Chang’s lighting design serves to build up the club atmosphere by blurring the boundaries between the stage and the auditorium, as the lights cross over to the audience, making them feel part of the party. Several times, a good number of audience members got up from their seats and danced, a rare sight in a Broadway musical, and continued their expression of appreciation with standing ovations. The high-energy musical performances present a variety of sounds, visuals, and performance styles that allow each number and the performers to stand out and further excite the crowd. Jennifer Weber’s choreography demonstrates a versatile range, with movements elevating each musical genre and style.

Kevin Woo and the Cast of KPOP. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy

The mellow numbers, on the other hand, cool down the atmosphere, filling the room with a mild sonic energy, and providing the audience with room to sit back and catch their breaths. The spoken scenes serve as musical resting places and forward the various plot lines. These scenes, rather than being foils to the musical numbers, help the audience invest in the characters and the dramatic progression. The characters speak in both Korean and English, with different levels of fluency depending on their identities and backgrounds. This mixture at times manifests in scenes of significant conflict and at others lightens the mood with language and culture-based humor. For example, when Ruby show up at RTMIS’s rehearsal, all RTMIS members stop what they were doing, bow to her, and greet her in Korean in unison with “안녕하세요, 사장님 (Ahn-nyung-hah-seh-yo, Sa-jang-nim),” a respectful way of saying “Hello, boss.” This brief greeting reflects Korean culture’s respect for an elder or superior. In the performance, it also had a comic effect for its sudden expression of an innate cultural habit.

KPOP effectively portrays a critical perspective on K-pop as a highly commercial, corporate, and manufactured product, which demands sacrifice of individuality and even artistic integrity. Ruby’s demands of MwE – “Use the pain [of losing your mother],” “Now it’s not the time to say things like ‘artistry.’” – and the pressure of being a superstar lead MwE to a near breaking point: “Everything breaks. Even machines. Even me.” Nevertheless, eventually the piece celebrates K-pop as a triumph, both artistic and personal. The versatile vocals, performance styles, and soundscapes are indeed the fruits of the sacrifice. The reward is the cheering crowds as well as the enjoyment the performers convey on stage. As such, KPOP leads to a climax with “Blast Off,” when everyone, both performers and audience, were up and jumping. Even though the audience remains in their seats, KPOP manages to create an immersive experience, with the escalating high-octane performances interspersed with poignant ballads and dramatic scenes of widely appealing narrative tropes.

Luna in KPOP. Photo Credit: Matthew Murphy

Transitioning from the standing ovation at the curtain call to the realization that this was the last performance felt like a rollercoaster, further reminding me of the problems in the industry that caused the short run of only seventeen performances post preview. It was reported that low ticket sales caused the closing. The production also suffered from a negative The New York Times review, which the producers and members of the cast and creative team criticized as racially insensitive, and which drew further criticism especially from BIPOC artists. In addition to the sadness that not more people will be able to enjoy this production is that discussion of this production will most likely be centered on the context of its early closing despite its historic milestone.

Possibly for the first time in Broadway history, the closing performance was followed by a post-show discussion, moderated by journalist Kimmy Yam and featuring playwrights David Henry Hwang and Hansol Jung, actor Pun Bandhu, KPOP composer, lyricist, and music producer Helen Park, and cast member John Yi, who played Danny, a member of F8. The discussion started with the panelists’ responses to the historical significance of KPOP’s achievement and its sudden closing – a mixture of pride and joy and anger and disappointment, which I also shared – and proceeded with a discussion of the state of Asian and Asian-American representation on stage and the importance of Asian-centered storytelling. Hwang, the first Asian American to win a Tony Award (1988, with M. Butterfly winning Best Play), brought attention to the question of how to bring the audience in for Asian-centered stories and how to make BIPOC audience feel welcome. Bandhu, who co-founded the Asian American Performers Action coalition (AAPAC) that publishes an annual visibility report on racial representation on stage, gave Broadway a failing grade in terms of representation – “80% white actors and writers, 90% white directors, 94% white producers” – while acknowledging the tremendous progress made by the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) community. Jung emphasized the importance of staying rooted in one’s identity and celebrating it as one’s human expression when creating stories. Park, the first Asian female composer on Broadway, shared her experience overcoming the obstacles and her desire to make other Koreans feel good about the show. Yi, who had been with KPOP since 2014, appreciated being in a show that cherished his identity as a Korean American. These are, of course, only the summarized main points the panelists brought up. A fuller examination of the broader significance of the issues would require more space and extended discussions. The panel served as a reminder that Broadway, and the US theatre scene in general, still had lots to do to make the stage more equitable and inclusive for both artists and audience and how rewarding it can be to create unique stories that embrace identities. An audience member, a young Asian woman, shared, in tears, how touching it was to see people like her represented on stage and wished the show would continue beyond this production.

Walking out of the Circle in the Square felt bittersweet, as I contemplated the future stage where productions such as KPOP could thrive and reap the rewards. While feeling somber, I also noticed myself moving rhythmically to the songs still lingering in my head. The mixed emotions and complex thoughts were balancing themselves through my physical motions. It dawned on me that maybe this state of simultaneously embracing multiple experiences – sensory, emotional, and intellectual – was approximating what “heung” – “spontaneous energy stemming from excitation, inspiration, play, and frolicking” – could bring.

My mind went to K-pop’s own journey from a local Korean culture to a global phenomenon. Several artists and companies over the years tried to break into the US popular music scene – which is known to be exclusive of artists from non-English speaking countries – by promoting themselves in the US market, releasing songs in English and/or collaborating with US artists. Some gained notable attention such as singer Rain topping the Time 100 Poll in the magazine’s annual list of most influential people in the world (2007) and starring in major blockbuster movies, Speed Racer (2008) and Ninja Assassin (2009), and Wonder Girls that, with their song “Nobody,” became the first K-pop group to chart in the Billboard 100, peaking at #76, in 2008, and served as the opening act for the Jonas Brothers World Tour 2009. Other examples, including “Girls” by Se7en featuring Lil Kim (2009), BoA’s English language album BoA (2009), “Ayyy Girl” by JYJ featuring Kanye West (2010), and “The Boys” by Girls’ Generation (2011), demonstrated more possibilities for Korean-US collaboration and crossover appeal. With Psy’s “Gangnam Style” (2012, #2 on the Billboard 100), K-pop exploded on the global stage, and the rest is history. Now K-pop has expanded its impact beyond music and has become a formidable presence in social media, diplomacy, politics, and scholarship. The musical KPOP, in this respect, can be located in K-pop’s rapidly expanding landscape and ongoing evolution. It has certainly planted the seed for K-pop and unique, original Asian-centered stories to bloom in the Great White Way.

* On May 2, it was announced that KPOP was nominated for three Tony Awards, Helen Park and Max Vernon for Best Original Score, Jennifer Weber for Best Choreography, and Clint Ramos and Sophia Choi for Best Costume Design of a Musical. The ceremony is scheduled for June 11, 2023.

* The KPOP Original Broadway Cast Recording was released in May, 2023.

[i] Suk-Young Kim, K-Pop Live: Fans, Idols, and Multimedia Performance (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018), 17.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Walter Byongsok Chon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.