Sydney Theatre Company’s new production of Macbeth may draw attention for its star, Hugo Weaving, but the most powerful agent of this production is the theatrical space.

Director Kip Williams has inverted the traditional theatre space: audience members enter through one side door and take their rather uncomfortable seats on what would be the stage/backstage of the theatre. In the program notes, Williams claims that “it is space that has conjured story”.

We stare directly out at where we should be sitting: the stalls and balcony seats are empty, dimly lit, and haunting. The vacant chairs are like dull eyes watching us, and their emptiness pre-empts the empty chair later in the play that the ghost of Banquo does and does not occupy (depending on who can see him).

Beautiful, clever lighting (by lighting designer Nick Schlieper) generates different moods for this seating space; at one point a faint blue lighting picks up the tops of the seats, which glint almost like water at night. The production sticks predominantly to the main stage space, but gradually and tentatively unfurls a little across the theatre.

Weaving onstage. Photo: Brett Boardman. Sydney Theatre Company

Banquo and Fleance are discovered by the murderers in the stalls, with Paula Arundel’s energetic Banquo hurdling over rows of seats in her attempt to flee, while Malcolm (Eden Falk) and Macduff (Kate Box) plan to overthrow Macbeth from the balcony.

Positioned between two seating areas, the stage of Macbeth is thus in a somewhat liminal space. The seating achieves a mirror effect which is simultaneously aesthetically pleasing and a little disconcerting. We are always reminded of ourselves as spectators, and this meta-theatrical tone suits the play. As Weaving’s eponymous protagonist reminds us:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.

But this is not to say that this production is experimental enough to lay bare its own backstage. Williams plays with the space but he does not transgress. Audience and actor are still firmly separate.

Weaving’s Macbeth

Weaving’s performance is captivating. In particular, his pacing is wonderful to behold. He has a habit of pausing and running on at unusual points, which keeps a listener’s interest.

While the space contends for attention, all else is designed to focus on the exploration of Macbeth’s inability to cope with the situation which he tortuously creates for himself. Weaving moves from a crumbling, terrified wreck, screaming and flailing on the floor in fear of Banquo’s ghost, to callously murdering the pregnant Lady Macduff and her young son.

Photo: Brett Boardman. Sydney Theatre Company

It’s an interesting portrait of a deeply unhappy and weak man who swings from one extreme to another, creating his own situation and then bemoaning his helplessness; he lashes out violently then reflects bitterly and deeply.

Macbeth’s final duel with Macduff is telling of this production’s focus on exploring Macbeth’s personal weakness. Williams, much like his take on last year’s Romeo and Juliet, brings his own very specific interpretation to the final scene.

Just as he did for King Duncan’s murder, he brings Macbeth’s death onto the stage. But instead of showing us a man who, despite knowing the witches’ prophecy won’t protect him, fights anyway, we see a man whose inability to “prick the sides of [his] intent” leaves him exhausted on the floor. Physically or spiritually, Macbeth gives up. Macduff kills him with a cool swipe of the hand across his face.

Where are the Witches?

This introspective focus on Macbeth’s personal failings comes at the expense of the witches, their supernatural aids, and the role of the supernatural more generally in the play. The witches suffer a significant loss of power and agency in this production.

In a piece which contains substantial doubling of roles, the actors identify themselves as the witches by immersing their faces in liquid, in a kind of odd baptism. The famous and deliciously evil first scene (“When shall we three meet again?”) fails to capture any magic.

It begins when the three witches – two male (Ivan Donato and Robert Menzies) and one female (Kate Box, who doubles as Macduff)–immerse their faces in a clear plastic container of water. The container is so utterly mundane, and the action (complete with gurgling) so ridiculous that it is completely non-magical.

In a later scene, the witches announce their presence or entry into the space by immersing their faces in other liquids–Menzies throws his face into a sumptuous white cake, Box into a bowl of milky cream, and Donato hits his face with powdered pastries. There is meaning behind it, but it’s lost in the distraction of the action.

The role of liquids in Macbeth–water, milk, and blood–are absolutely central and intrinsic to the play. We see this in Macbeth’s complaint that:

Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood

Clean from my hand? No: this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red.

We see it also in Lady Macbeth’s call for “murd’ring ministers” to “Come to my woman’s breasts/And take my milk for gall”, and, of course, in the stubborn stain of blood that smears the entire play.

This seems to be what the witches’ use of liquid is connecting with, but the awkward comedic nature of this action undoes any power this choice may have. Throughout, the audience responded with a slightly awkward desire to laugh at what my companion called the “face-planting”.

The witches’ integration with the rest of the ensemble, along with the omission of Hecate’s scene, further weakens the preternatural power that stalks this play.

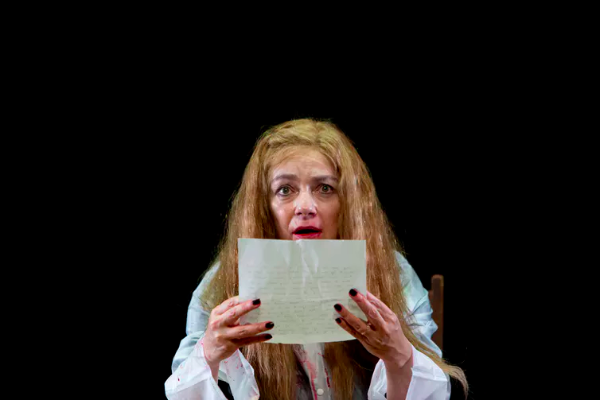

Melita Jurisic as Lady Macbeth. Photo: Brett Boardman. Sydney Theatre Company

The play really finds its feet and draws you in following Macbeth’s murder of King Duncan (played elegantly by John Gaden, who also doubles up as Young Macduff). After the murder, a resonant and rhythmic tapping grows to a crescendo of knocking, at which point the stage and audience are blasted with a thick fog.

Everything is obscured from sight. The fog hovers into the next scene, obscuring the stage and leaving only the actors’ faces vaguely visible in a sea of mist. Then, suddenly, a cold wind blasts the fog away. It is in this moment that I first felt the preternatural mood of this play.

We find this again later in the snowy rain of glittering confetti that begins to fall on Macbeth’s last scenes. During his “tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” speech, Macbeth uses his sword to draw a figure eight–a symbol of infinity–in the snowy ground.

The production has moved the sense of the mysterious unknown usually conjured by the witches into these physical forces of fog, wind, and glittering rain. These are tied far more closely to Macbeth than they are to the supernatural.

Hugo Weaving and Melita Jurisic onstage. Photo: Brett Boardman. Sydney Theatre Company

The play fits tightly within a two-hour timeslot (no interval). The editing generally seemed to work unproblematically, but I very much regretted the omission of the Doctor and the Gentlewoman discussing Lady Macbeth’s (Melita Jurisic) mental health. Instead, Lady Macbeth’s final and famous scene (“Out, damned spot!”) is merged with Macbeth’s following scene.

This choice weakened Lady Macbeth’s dominance in the production; indeed, from the beginning, Lady Macbeth seems out of her depth. We don’t ever see her in control of her own female, political, or supernatural power; she is always flustered and emotional.

Photo: Brett Boardman. Sydney Theatre Company

As Penny Gay states in the program essay, Lady Macbeth’s character is at one stage “so sure of her ability simply to move on from unpleasant situations and repress the knowledge of what has been done”. This doesn’t come across in performance.

This production is focused on exploring two things: that strange space of the theatre, with its eerie emptiness and its always fleeting occupations of space, and Macbeth as an isolated, introspective man.

It is immensely interesting but comes at a cost: for me, some of the uncanniness was lost, as was the fascinating devolution of Lady Macbeth. STC’s Macbeth is a more abstract and ambiguous piece than the crystal clarity of Bell Shakespeare’s recent Henry V–but that is not to say that one style is preferable.

Macbeth is less interested in verisimilitude than in a complex and spatial expression of Macbeth’s rather solipsistic worldview.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on July 29, 2014, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Claire Hansen.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.