Outwitting the Devil, Akram Khan’s latest work, truly stood out within the line up of very diverse works featured at the 2019 Avignon Festival. Performed at the magnificent Cour d’honneur du Palais de Papes this work resonated the architectural grandeur of the space and echoes its spiritual splendor. It reflected the palace’s glory through its own choreography, mythic themes, and hypnotic sound and lighting designs.

Akram Khan, a British dancer, and choreographer of Bangladeshi descent captivated the world of contemporary dance in the early 2000s. A student of the kathak, a traditional Indian dance, he performed in Peter Brook’s Mahâbhârata. Later he created highly experimental solo and ensemble work that would draw his viewer’s attention to the hybrid language of dance as invented by Khan himself, the language in which traditional elements of the Indian dance would neighbor and dialogue with many components of western performance. To enrich his vocabulary, Akram Khan engaged dramatic narrative and humor, approximating in his style the so-called tanz-teatr as developed by the German choreographer Pina Bausch.

Outwitting the Devil is truly the work of a genius and a mature artist: not only does it amalgamate the artistic devices that make Akram Khan’s signature style; it also takes his language to a new level. By creating poetry and myth on stage, in Outwitting the Devil, one might say, Akram Khan has overcome his own self. He transformed the stage of Palais des Papes into the space of warning; and thus, he made the audience confront the devastating truth of Anthropocene.

Seeking resolutions to climate change and searching for ideas on how to deal with today’s environmental crisis we tend to look at the future, trying to fix the present from the position of what is yet to come, Akram Khan said in his press conference. Working on this project, he realized that the answer to our present worries lies in our past. To fix mistakes we have already made, the choreographer continued, humankind must look back at the knowledge engraved in our history, as it is the past where the secrets to our future lie. Outwitting the Devil, as Khan explained, began with the idea of outwitting time, i.e. time standing for the word “devil” in the title of this project. Gradually, however, it became clear to the artist and his team that the devil of this story is human- an ungrateful creature only capable of destroying everything and everybody around him/her.

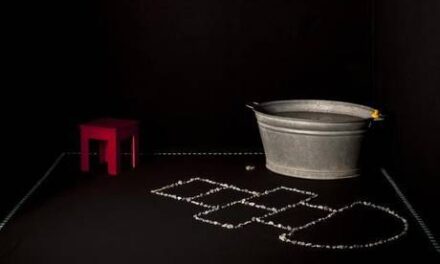

Tom Scutt, the set designer for this show, covered the massive stage of the Palais des Papes with small rectangular cubes or clay tablets, referencing through this image both nature, seized by humans, and knowledge engraved in it. Six dancers of different ages and performance traditions made a dramatis personae of this complex narrative, which reflects in its structure, themes and images that Akram Khan and his dramaturge Ruth Little call the “founding stories of our civilization”. These stories include a newly discovered fragment from the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, a poem by Persian mystic Rumi, and Leonard da Vinci’s Last Supper. The texts written by the English Canadian writer, Jordan Tannahill, serve as a framing device for this composition.

Outwitting the Devil. Photo Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

The story of Gilgamesh, a semi-divine king, and his moral lessons is the leading motive of the multilayered dramaturgy that makes Outwitting the Devil. Next to Gilgamesh, who appears here both as a young warrior and as an older king, there are his beloved servant, Enkidu, who used to be wild until one temple priestess civilized him; a young woman whom Gilgamesh desires; Goddess Ishtar, and Bull of Heaven. As Gilgamesh becomes more powerful, merciless and arrogant, Gods begin to fear that they lose control over him. When Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill Bull of Heaven, Gods lose their patience and punish Gilgamesh by getting rid of Enkidu.

The second part of the narrative describes Gilgamesh learning the consequences of his actions: through the act of mourning, he turns good. He recognizes the impossible price one must pay for being immortal, and so he accepts his death and repents. He also realizes that to learn this truth one can do it only by assuming a position outside oneself, i.e. by looking at one’s own destiny through the distorted mirror image of this self. That is why, on stage, Outwitting the Devil, brings out not one but two protagonists: an older man looking at his younger self, realizing how devastating the results of his deeds are, and a younger man actively engaged in making these deeds happen.

The strength of Akram Khan’s choreography is in his dancers, as each performer brings the uniqueness of his/her training, style, and personality on stage. On the night of July 18th, when I attended this production, Andrew Pan, cast to dance the part of Enkidu injured his Achilles heel. The show had to stop as it had become dangerous for the company to continue with the performance. Before the accident, however, it was simply impossible to turn your eyes away from this dancer, who is literally transformed into the wild creature Enkidu, with every movement and muscle of his body used to draw the graphic picture of Enkidu’s physical existence on stage.

Outwitting the Devil. Photo Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

Outwitting the Devil, however, does not privilege one single performer. It is an ensemble piece based on the intricate design of gestures and moves the dancers make and the elaborate system of inter-personal connections that mark Khan’s choreography. This meticulously thought through and calligraphically executed collective work transmitted the philosophical exigency of Khan’s narrative and created the mythic atmosphere of a new theatre epic. I was fortunate to see this dance for the 2nd time, on the night of July 21st, when Mavin Khoo, the rehearsal director of the play, took the place of Andrew Pan. His work was impressive as well, but it changed the intensity of the inter-character’s relationships on stage and brought different overtones and meanings to the performance.

In the slowly building ambient soundtrack mixed with the primal sounds of nature, such as falling rocks of rushing water, an old man appears stage right. He carries a large cube, possibly a tablet with Gilgamesh’s engravings. This tablet signifies both the weight of man’s age and ignorance, and his sins he is yet to recognize. The man feels that his strength is leaving him, while his memories take over his reality and the creatures of his past invade his present. The production ends with the magnificent image of this man’s death, as the wild creatures of his past and the Goddess Ishtar, perform their own dance macabre. Danced by Mythili Prakash, who uses Bharatanatyam, the cosmic performance of Lord Shiva, the Goddess Ishtar dances her magic out: as we see Gilgamesh falling into the rabbit hole of time; she- the goddess of life and death- stands intact ready to protect her kindred.

In this last image, I believe, Akram Khan articulates his warning- the Goddess, who can only stand for the image of nature and earth itself- is more powerful than humankind will ever know or will ever be able to understand. Today our collective destiny is similar to that of Gilgamesh, but only if we do not make an effort to change our behavior and thus ensure the transformation of our own future.

Outwitting the Devil

Artistic direction and choreography Akram Khan

Text Jordan Tannahill

Dramaturgy Ruth Little

With Ching-Ying Chien, Andrew Pan, Dominique Petit, Mythili Prakash, Sam Pratt, James Vu Anh Pham

Music and sound Vincenzo Lamagna

Lights Aideen Malone

Stage design Tom Scutt

Costumes Kimie Nakano

Video Maxime Dos

Artistic collaboration Mavin Khoo

Production Akram Khan Company, in co-production Festival d’Avignon, Théâtre de Namur Centre scénique, Central Centre Culturel de La Louvière, Théâtre de la Ville (Paris), Sadler’s Wells Theatre (Londres), La Comédie de Clermont-Ferrand Scène Nationale, Colours International Dance Festival 2019 (Stuttgart), and in partnership with France Médias Monde

Cour d’honneur du Palais des papes, Avignon Festival, July 17-21, 2019

This article was reposted with permission from the Capital Critics’ Circle. It was originally published on August 1st, 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yana Meerzon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.