Nicolai Khalezin is the director of the Belarus Free Theatre’s newest production Red Forest. He co-founded the company along with his wife Natalia Kaliada and their collaborator Vladmir Shcherban in 2005. In 2011 Khalezin, Kaliada, and their family were granted political asylum in the UK. Since that time they have continued to produce new work both in Belarus and around the world. Khalezin talks about Red Forest, about the role of theatre in times of repression, and about life in political exile.

Tell us, what was the initial inspiration for your new play Red Forest?

NK: The idea behind Red Forest grew out of an interest in the term ‘climate change.’ We became interested in the relationship between these two words and wondered how we could shape that relationship into something concrete. ‘Climate change’ is a popular phrase that lots of people use these days, even though most people have no idea what it really means. So this was our initial task which, in the end, turned out to be much more complicated than we had anticipated.

How did you conduct your research in preparation for the show?

NK: We began by talking to experts who explained the science of climate change as it relates to nature. They told us why climate change is not merely a matter of rising temperatures and changes in weather patterns but results from a synthesis of factors such as geopolitics, geophysics and public behaviour. They explained why such influences cannot be separated…. After these meetings, it was clear to us that we needed to identify specific world locations where the effects of climate change were most severe. These locations included Brazil, Bolivia, and areas close to the Amazon. The next locations we visited were India and Bangladesh and, third was Central Africa. Despite the differences, we understood that these phenomena all share one thing in common. People are fleeing. People are being chased from their homeland. In Rio do, Janeiro refugees are running from the gas companies. In Nigeria, families are fleeing from the war over water. All of these people have been forced out of their homes. They have become homeless. So, when we understood this commonality, we understood the project, because we were also forced to flee from our home.

You live here in the UK but many of your actors continue to live and work in Minsk. Could you explain how you work with them from afar?

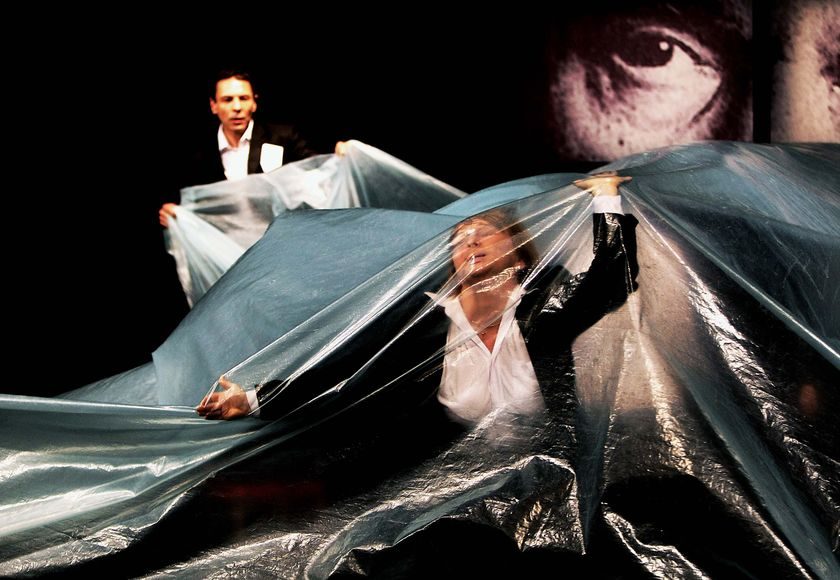

NK: Yes, that’s right. We have been performing in our small venue in Minsk at the same time that we perform our work in theatres all over the world. As you know, some of us are no longer able to work in Minsk for political reasons, but our actors continue to work there. Half of our current productions are performed in conjunction with our residency at Falmouth University. The other part of our work is conducted over skype. For these shows, the actors work in Minsk and the directors work from here…. So that’s all really. We have these two different ways of working. The plays we rehearse over skype are the minimalist plays that are built specifically for Belarus. The bigger projects like Red Forest, Trash Cuisine, and King Lear have more extensive technical requirements so of course they cannot be performed there.

Is it not dangerous for your actors to travel back and forth for the shows?

NK: Travelling to and from Belarus is not the dangerous part. The dangerous part is performing at home. Ours is a new kind of dictatorship. It isn’t the Soviet type in which everything is closed and you can’t get out. Now it’s quite the opposite. They say go, all of you can go. They want you to leave so as not to have people like you there at all. The problem is in staying there. We had an incident recently, for example, when the woman from whom we rented our small space received a visit from the KGB. They told her she had to evict us or she would lose her home. We left on our own because we didn’t want to cause her more problems. Now we perform in various locations that we are lucky enough to find. So yes, it is dangerous. Our actors have been expelled from university and fired from state theatres. They’ve been arrested and they’ve been in prison. We all fight these battles though so for us it’s the norm. Here in the UK stories like this are unusual but for us they are normal and they have been for almost twenty years.

In your opinion, can theatre influence social policy?

NK: Of course, the theatre has a very strong influence. In fact just today we led a protest on Millennium Bridge with the cast of Red Forest. It was an event intended to raise awareness about two issues. The first has to do with the nuclear plant currently under construction in Belarus that fails to meet international safety standards. It’s an absolutely insane story. The second objective of today’s protest was to address the dangers of fracking in the UK and around the globe. Another example of the connection between theatre and social policy can be seen in our production Trash Cuisine which is about capital punishment. Belarus is the only country in Europe where the death penalty is still legal and our show asked people to think about that fact and to talk about it. Of course, theatre can only have an influence on social politics if people want it to have an influence. If a director would rather maintain a classic repertoire and build a calm environment with no conflict in order to protect one’s self, then, of course, that work will have no effect on the political situation. It’s not easy to make a difference. You have to be more than a good playwright or a good director. You have to actively engage with politics. You have to keep track of developments in science, art, and currents events. So, in practice, very few artists’ collectives are making truly challenging work.

How do you conceive of the role of theatre in times of repression as distinct from film or fine arts for example?

NK: There’s basically no difference. In the end, it’s all the same. If an artist makes something that really matters it makes no difference whether its film, fine arts, or theatre. All that matters is that you actually do something. The world needs more artists willing to make these kinds of changes but we don’t have enough people who are truly ready to confront the situation. For example, we’re speaking out against fracking. What do you think, how many of arts and culture foundation have board members who also work for companies that support fracking?

I don’t know, probably a lot.

NK: Almost all of them, almost every single one. Now we’re getting to the heart of the conflict. Here’s another example: our American friends adored our show Trash Cuisine and would have loved to have us perform it there but, we never could. How can they produce a play about capital punishment? You see, half the struggle in the theatre is with the people who pay for it. Why would they waste money on people who are simply going to speak out against them? It’s completely straightforward, there’s no nuance. It’s just that simple. Are you against the construction of this nuclear power plant? Well, we have six people on our board who are involved in the project so what do you want from us? You want us to give you money so you can mobilize against us? It’s that simple. If I were a writer I could sit at home with my computer and I could write what I wanted. If I were a painter I could retreat from the world around me and continue to work. But theatre is a collective art and that makes it more complicated. You have to make compromises, that’s what it means to work as a collective.

Do you think there will come a time in the future when you will be able to return home to live and work again in Belarus?

NK: I’ve grown tired of asking myself this question. I have my family here and that is most important. What else is there for me in Belarus? I used to have a house. I used to have my parents. I still have one brother who lives there but he can come here or we can meet somewhere else. In fact, he just left London three days ago. So I don’t ask myself this question anymore. If I did I would just sit and wait for the moment when I could go home and I can’t just wait because I have work to do.

It’s actually the last question I want to ask myself, whether or not I’ll ever return to Belarus. To return or not to return? Will circumstance ever allow it? I want to make theatre, I want to make films, I want to write books, these are things I know for sure.

Our friend Mikhail Baryshnikov immigrated and never once went back to Russia and he never will. He knows that atmosphere and he knows nothing good would come of it. He knows he would show up there and think, ‘well, now what’? He would arrive and then he would leave.

Joseph Brodsky was the same. They were friends, by the way, their whole lives. Once they were sitting somewhere in Helsinki and you know, only the Gulf of Finland stands between Helsinki and St. Petersburg. So Brodsky says to Baryshnikov, ‘Misha, let’s go sit on the bank. We can drink a little vodka, look over at Petersburg and then turn back.’ And that’s what they did.

I have my family, my art, my work, my contracts here now and, I know that if I were to go home, even if without the political threat, I would have to start all over again building a new life. That knowledge makes it harder to think about ever going home. You know, life just keeps going whether or not the dictatorship remains.

This article was first published in Central and Eastern European London Review. Reposted with permission of the author. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Molly Flynn.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.