If there is such a thing as typical Circa Theatre fare, Hand to God is certainly not it, yet the typical Circa opening night audience is wide-eyed and beaming in its wake: they love it!

The word according to Tyrone – the puppet who delivers the prologue – is that the trouble started when we stopped being carefree individuals and took to living in communities (sorry Maggie Thatcher: there is such a thing as ‘society’); when we invented ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ – and ‘the Devil’, who could be blamed for the bad stuff a person did so they still got to sit around the campfire. Thus the agenda is set.

The community we are plunged into is a club room in (according to the programme) the basement of a church in suburban Cypress, Texas, USA – where playwright Robert Askins was born in 1980 (the Texan community “where the country meets the city,” that is, not the basement).

Margery is trying to teach three young teens – Jason (her son), Jessica and Timothy – how to make puppets. Wiki’s online synopsis informs us, “Fundamentalist Christian congregations often use puppets to teach children how to follow the Bible and avoid Satan.” To engender a greater sense of purpose, Pastor Greg declares their puppet show will be “on the bill” for the whole congregation this coming Sunday.

The recently widowed Margery is too preoccupied with her own feelings to register that he son Jason may be hurting too, from the loss of his father. By contrast, Timothy, whose mother is rarely sober, is ‘acting out’ with aggressively macho, sexually predatory and abusive taunts at Jessica and Jason. And Jessica takes refuge in her Jesus-loving, work-in-progress puppet.

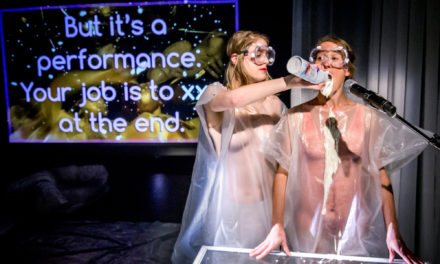

So far (apart from the prologue) it amounts to the basis for a poignant plotline in a soap opera. Here, however, Askins exploits the ‘devil’s advocate’ puppet, Tyrone, in ways that would never be allowed on free-to-air television (shades of Sesame Street parody Avenue Q). Indeed Tyrone, and Jessica’s puppet in one scene, get away with behaviour we would judge quite differently played out by human characters.

That said, Margery and Timothy do shock and surprise us in ‘real life’, as it were, in ways that challenge our socio-political sensibilities on a number of levels … I won’t say how: see for yourselves.

The master-stroke in the writing of this play is that in direct counterpoint to the simplistic ‘good/evil’ binary beloved by fundamentalists, all five characters are fallible, vulnerable and complex, revealing truths that seem to contradict the characteristics they present in public in order to protect themselves.

Without missing a beat in this dynamically-paced and judiciously modulated production, director Lyndee-Jane Rutherford and her ideal cast – including the hand-puppets, designed and constructed by Jon Coddington – ensure we get it all, eliciting whoops and hollers at their outrageous antics one minute and sighs of profound empathy the next.

Tom Clarke rises with alacrity to the exacting challenge of juxtaposing the split personalities of the introverted and sensitive Jason with the hyper-expressive and increasingly insensitive, yet bluntly honest, Tyrone. Even as we thrill to Tyrone’s outrageous antics, and Tom’s skill at vocalising and physicalizing his puppet, our guts are gripped by empathy with his internal battle.

Jack Buchanan surprises us greatly as his appallingly-behaved Timothy, overdosed on testosterone, flips to reveal his true needs and feelings, even though the boy’s means of expressing them remain highly questionable.

Amy Tarleton plays Margery’s maelstrom of emotions with extraordinary skill, revealing her lost-in-bewilderment state just as we are about to harshly judge her self-centredness and abusiveness.

As her would-be replacement “open arms,” Peter Hambleton’s Pastor Greg likewise engenders compassion, despite the patronising nature of his ingrained patriarchal conditioning.

Jessica is the slow-burner in the story. Hannah Banks inhabits her relatively silent being with a compelling truth then, just when I’m thinking she’s been short-changed with an under-written role, she too finds an agency in her now a fully-functional puppet, Jolene. The scene where Jessica and Jason counterpoint their tentative teenage bonding with Jolene and Tyrone’s lustful consummation is an exceptional high point among many.

Ian Harmon’s lively set and Jennifer Lal’s lighting design are active participants, and Darlene Mohekey’s sound design enriches the experience even more.

With the Jason/Tyrone dichotomy its centre and everyone looking for love and companionship, often in bizarre and inappropriate ways, Hand to God is a hell of a ride. Hugely entertaining, I’d venture to suggest it also gives each of us an opportunity to see how we too could become ‘possessed.’

Its implications in the real world will resonate differently for everyone. For me, it offers an insight into how the religious right can be so ill-equipped to deal with life’s complexities that they believe in someone like Trump and vote him in despite – or perhaps, in part, because of – his own gross behaviour.

By Robert Askins

Directed by Lyndee-Jane Rutherford

Circa Theatre, Wellington, New Zealand

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Smythe.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.