Filmmaker Sun Yang discusses his recent documentary about visual artist Ma Liang, also known as Maleonn, and the creator’s attempt to tell a story of family, reconciliation and reclaiming lost memories through the lens of steampunk puppetry.

BEIJING — When his father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, Chinese visual artist Ma Liang suddenly found himself in a race against time. Before dementia eroded their shared memories, he had to work quickly with his father, an acclaimed theater director himself, to complete an ambitious project: create art together.

That was in 2014. The art project eventually became Papa’s Time Machine, an autobiographical play using steampunk-influenced life-size mechanical puppets, which debuted in Shanghai in early 2017. The play told the story of a father-son duo traveling through time in a machine to relive their fondest memories.

But in reality, the memories are more fragile. Ma Liang’s father Ma Ke watched the debut but quickly forgot the plot, forgot he attended its opening, and forgot he helped his son put the show together.

The project, the intricate designs, and the complex puppetry had consumed four years of Ma Liang’s life, and though his father’s disease seemed unstoppable, he said the work was the “only way to get close to him.”

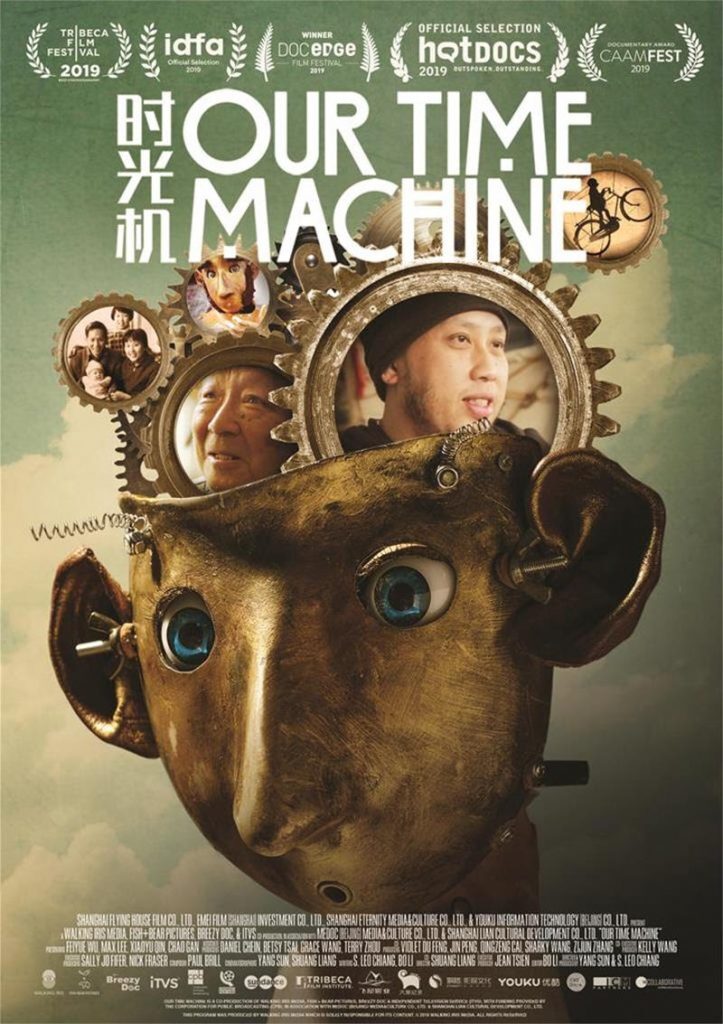

Now, that play and the fairytale-like story of Ma Liang’s family and art lives on, faithfully documented in Our Time Machine, a 2019 documentary film directed by Sun Yang and S. Leo Chiang. It has since taken on a new life, traveling farther than the original play through worldwide screenings.

Chronicled between 2015 and 2018, the film takes viewers into the storied life of three generations of a middle-class family in Shanghai, who candidly express the burden of coping with Alzheimer’s disease. The film primarily features Ma Ke as the patient, his wife Tong Zhengwei as the care partner, and Ma Liang as the middle-aged son.

Ma Liang’s family wouldn’t look out-of-place were they from cities with a more internationally recognized art scene, such as New York — privileged enough to have received an education, financially secure but not affluent, and able to foster intellectual and creative pursuits. Ma Liang’s parents, both theater workers, have two children: him and his sister, Ma Duo.

Considered among China’s most influential modern visual artists, 43-year-old Ma Liang, also known as Maleonn, has created several significant art pieces. This includes a grand project for which he traveled across 25 Chinese provinces, photographing 200,000 people in a mobile photo studio.

But when it came to theater, Ma Liang was a rookie. His father, though, has 80 Peking opera titles under his belt, having retired from the Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company — something he even reminisces about in the film.

Not long ago, state-owned performing arts companies dictated the cultural sphere before subsidies were cut and businesses started to reform. The documentary also highlights the highly competitive current-day Shanghai theater scene — in stark contrast with his father’s achievements in theater, Ma Liang struggled to attract enough funding, almost giving up production midway.

Despite being fleeting and subtle, Our Time Machine also introduces a curious juxtaposition of memory loss and health with an unexamined era of political turmoil in the country: Ma Liang’s parents were among the “sent-down” youth forced to work on farms in the 1960s and ’70s, where Ma Liang was eventually born.

A promotional poster for Our Time Machine shows Ma Liang tinkering on a project. Courtesy of Sun Yang

Growing up in the shadow of the decade-long Cultural Revolution and the years following China’s economic reform, Ma Liang’s generation of artists lived through dramatic socio-economic transformation. They witnessed the widening wealth gap and the replacement of old norms along with globalization and digitalization. It’s where Ma Liang’s personal and artistic style stems from.

By the end of the documentary, Ma Liang manages to reconcile with the reality of fading memories. Initially frustrated and heartbroken that his father frequently repeats the same sets of questions, Ma Liang learns to enjoy seeing the excitement on his father’s face each time he asks the same thing and takes it anew.

The film also captures a party celebrating the first month of his daughter’s birth, where Ma Ke is unable to recognize the infant. “I feel fine introducing her to him over and over again saying, ‘yes, this is your granddaughter,’” Ma Liang says in the film.

The 81-minute documentary debuted at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival. It’s the first feature documentary by Sun Yang, a Beijing-based director, who previously made mid-length documentaries for Yixi, regarded by some as the Chinese equivalent to TED Talks.

Sun found his partner, S. Leo Chiang — a Taiwanese American filmmaker and documentary branch member of the Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences — at the annual CNEX Chinese Doc Forum in Taiwan. Our Time Machine is currently streaming online for a limited time, with a China release date to be announced.

A still frame from “Papa’s Time Machine.” From Our Time Machine 时光机 on Facebook

Speaking with Sixth Tone, Sun Yang discussed the years he spent with Ma Liang’s family for the documentary. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: How did you first get engaged in the story of Ma Liang and his father and decide to make the subject your first feature-length documentary film?

Sun Yang: Let me tell you a story that Ma Liang told me, a story that happened in a swimming pool. As soon as I learned about this story, I thought to myself that it was going to be my favorite story since graduating (from graduate school in 2013).

(Imagine) a starry night in a blue swimming pool, the father at the poolside, the son swimming laps. The father is worried about the son. The son reassures the father that he learned swimming from him as a child. This scene is repeated over and over, and you can see time, aging, and everything. I wanted to make a film just for this scene — I did not know whether it would turn out short or long, but I wanted to make it happen.

At the time, my biggest confusion was how to continue creative work in a seemingly endless void for the rest of my life. But in Our Time Machine, Ma Liang was confronting reality with his imagination, and I wanted to seek an answer for myself from it.

Sixth Tone: Alzheimer’s disease is the backdrop explored throughout the film. What have you learned from working on the four-year project?

Sun: (Alzheimer’s) is common. In many screening Q&As I have done, people have told me that their grandparents or parents had Alzheimer’s. If cancer destroys the body, Alzheimer’s destroys the spirit. It removes memories, characters, and personalities, turning you into a complete stranger.

Ma Liang’s father used to be a particularly strong and charismatic director. In Ma Liang’s words: “He protects the family like a male lion.”

An old photo shows Ma Ke, Ma Liang’s father, directing an opera rehearsal. From Our Time Machine 时光机 on Facebook

And he was the director at the Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company, enthusiastic about work, rehearsing with a crew of over 100 every day, studying scripts even when off-duty. That was what everyone knew him as. The disease changed everything.

Others may not realize it, thinking having Alzheimer’s is fine as long as the person is taken care of. But for families, the emotional challenges can be unbearable.

Sixth Tone: The earlier relationship between Ma Liang and his father isn’t explored as much in the film. Can you give us a better idea about why he wanted to design this stage performance for his father?

Sun: Shortly after Ma Liang was born, it was a period of reinstatement after the Cultural Revolution, and the art world was eager for Ma Ke’s return. Having waited for 10 years, Ma Ke put everything into creative work and spent little time with Ma Liang.

In a scene, the two sing Peking opera, and Ma Liang tells his father that he never taught him to sing; he learned from others. Young Ma Liang was interested in art, because he wanted a line of communication with his father — real communication. Ma Liang thought that by creating with his father, they’d become closer.

In the movie, Ma Liang appears very warm with his father, but there is a sense of distance and estrangement. Their relationship did not change in the four years (of putting together the stage performance). The real change happened internally for Ma Liang. From a wish, to disappointment, to finally coming to terms with reality, which meant no more heartbreak.

A poster for Our Time Machine. Courtesy of Sun Yang.

Sixth Tone: The generational gap between the father and son is unique to contemporary China. What are some societal transitions the family has collectively witnessed?

Sun: Ma Liang and his father have lived through almost everything in modern China. His father was born in 1930, brought up against the backdrop of the war against Japan. In fact, his father fought in the war himself. Then, the People’s Republic was founded. Ma Liang was born in 1973, during the Cultural Revolution. Soon, it was “reform and opening-up.”

Ma Liang’s father is a very good person, a “red” artist born in a time of collectivism. He is the sort who can give everything to his motherland, to Peking opera. Artists today still give their all, but are driven by individualism. Ma Liang, in contrast, started to paint as a child and has always been someone who does not follow others’ paths. He became an advertising director after college, sold the company at the age of 30, then went on to become an independent artist.

Sixth Tone: Why did Ma Liang choose steampunk puppetry, which is completely different from Peking opera, if he wanted to pay tribute to his father?

Sun: First of all, steampunk is one of Ma Liang’s signature styles. Projects including his mobile photography studio can all be considered steampunk.

Why puppetry, then? Ma Liang wanted a father-son story, with the prototypes being him and his father. He found it strange to use two actors, so he decided to do something abstract. Puppets don’t talk: Isn’t that normal for father and son?

I think a subtle metaphor about puppets is that they are being operated. Without an operator, the puppet is lifeless. Many people live without a soul, as if they were dead, as if they were puppets.

Ma Liang rests his head on his father’s shoulder. Courtesy of Sun Yang

Sixth Tone: The current generation of artists seems to have lost interest in stable jobs “within the system.” What is at play, and what piques your interest about an alternative narrative?

Sun: Graduates are anxious about the future, and this anxiety is the main drive for job-hunting. The better the job you find, the lower your anxiety. Many people are not brave enough (to take more risks), including many Chinese college students. I don’t blame them: Their families aren’t particularly rich, so they need to gain earning power. On top of that, the expectation is for them to get married, buy an apartment, and become successful in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. If you don’t manage the anxiety, all this talent will be wasted.

I’m not saying I found a way to achieve those goals. I just dealt with this anxiety with a bigger anxiety: I plunged into creative work without knowing where my future would be. When I was making this film, I also wanted to find an answer for myself. I wanted to know what Ma Liang was going to do, experiencing a midlife crisis with his creative work.

In the past five years, new Chinese documentaries and filmmakers have emerged on the international stage at an incredible pace. People like me get to find early funds to concentrate on work without interference. If you find a good story and everyone tries to help, you will feel hopeful.

This article was originally posted at sixthtone.com and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Fu Beimeng.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.