Australia’s performing arts sector has long been recognized as an ecosystem. It is a community of artists, arts organizations and institutions, all affected by factors such as education and training, audiences, policy and revenues.

It comprises commercial organizations; not-for-profit, government subsidized companies; independent grassroots ventures; and amateur groups making and touring creative works for audiences locally, nationally and internationally.

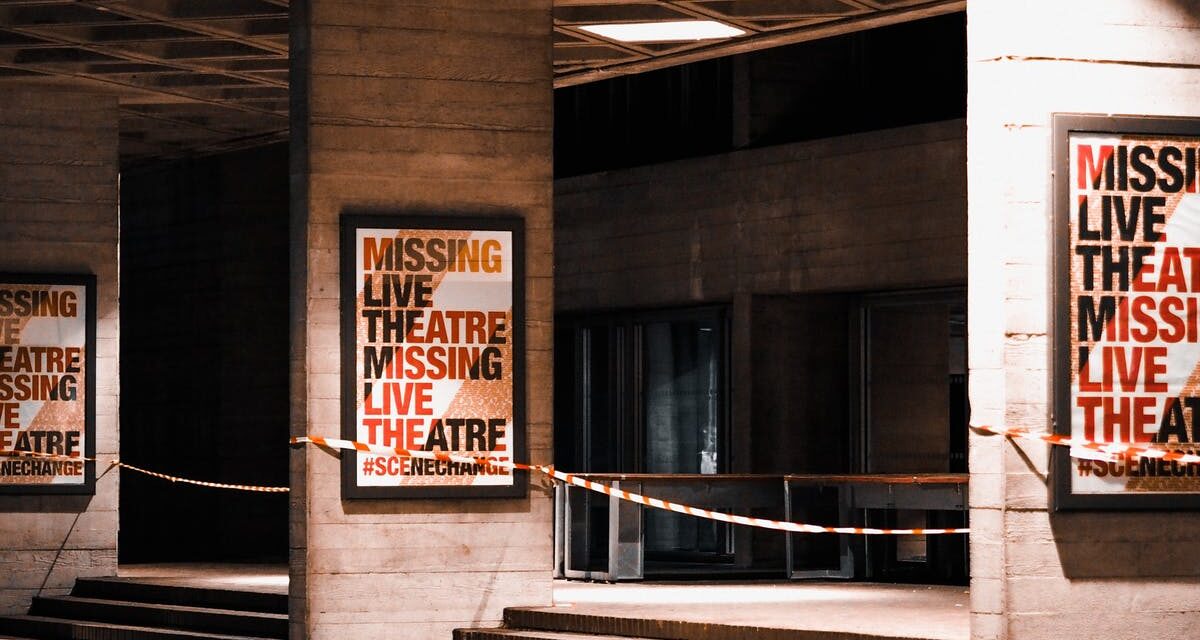

Every species in this ecology has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As we transit from crisis to recovery, and the dust settles on a post-COVID terrain, it’s likely we’ll see a mass exodus of despairing freelance workers leaving the sector for good.

The demise of small companies lacking the infrastructure to survive is also on the cards. A decimation of university theatre departments has already happened. Taken together, this paints a bleak future.

The sector has called for extra support for over a year. Theatre Network Australia proposes additional funding of $100 million over four years for the Australia Council and a targeted wage subsidy for workers in the performing arts who continue to suffer due to COVID-19.

For the top tier, hope is to hand. With swiftly rising vaccination rates, theatres in Sydney have been given the green light to open at 75% capacity. Big stage musicals Hamilton and Come From Away will reopen this month. Sydney Theatre Company will return in November with Julius Caesar and plans to mount an international tour of The Picture of Dorian Gray, starring Eryn Jean Norvill, with commercial producer Michael Cassel Group.

Sydney Theatre Company has announced they will be touring “The Picture of Dorian Gray” – but the path forward for smaller companies will be much more rocky. PC: Dan Boud/Sydney Theatre Company

Melbourne theatres remain closed until a “pathway” beyond the peak of the pandemic is settled, but there is clear hope theatres will open in the coming months. Melbourne Theatre Company has just announced its 2022 season to start in January.

These companies were able to weather the storms of 2020 and 2021. Many smaller companies and independent artists may not be so fortunate. With state borders still closed and lower vaccination rates in regional areas, the resumption of touring remains a long way off.

COVID-related funding losses have seen drama departments at seven universities either cut completely, or drastically pruned. The loss of these programs will have a devastating impact on future generations of artists and arts educators..

The end of the pandemic may be in sight. The pain for Australia’s theatre sector is only just beginning.

“Caught in a rip”

The COVID-19 Arts Sustainability Fund was established by the federal government in June 2020, three months after COVID closed theatres and venues and halted touring, triggering unemployment – or significantly reduced employment – for the sector’s large base of freelance workers.

The $50 million fund remains open until May 2022 to provide “last resort” assistance to “significant” arts organisations at “imminent risk” of insolvency due to the pandemic.

A $5 million cash grant to the Melbourne Theatre Company is the latest lifeline from the fund to rescue one of our leading cultural organisations from going under. As the company’s executive director, Virgina Lovett, described it, the pandemic has been “like being caught in a rip”.

The term “imminent risk” evokes urgency: a clear and present danger.

Yet this language of pending disaster is a curious metaphor for the government to use, given the changes to Australia’s subsidised performing arts industry across the last seven years.

Melbourne Theatre Company recently received money earmarked for companies at “imminent risk” due to the COVID crisis. PC: Jo Duck/MTC

Federal government funding for the arts is less now than 2013 when the Labor government departed office. Australia lags in the OECD league table for spending on culture per percentage of GDP. In 2019, Australia ranked 25th in a field of 34 countries, spending just 0.9% of GDP on culture.

The reality is that COVID-19 is just another deadly blow to an arts ecology that has been endangered for a long time.

The bulk of the government’s COVID-19 response for the arts sector is its project-based, $200 million competitive grant fund, Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand (RISE). So far, $160 million has been allocated to a mix of regional and metropolitan organisations; commercial and not-for-profit; touring, events, festivals and exhibitions. It is a much broader church of recipients than the typical roll call of Australia Council funding.

A devil in the detail is support for touring projects and initiatives in the regions: touring funding is of little use if it can’t quickly leverage return through buoyant ticket sales, and vaccination rates in regional areas will remain low for some time to come.

The crisis in drama departments

There will be an unmeasured – and perhaps immeasurable impact – on emerging and independent artists. In many cases, COVID has broken trajectories of creative development begun in childhood, developed through teenage years and honed in higher education.

Young emerging artists provide generational renewal to theatre: bringing ideas and energy into the rehearsal room as they find their voices as creators and collaborators.

But pathways for them to hone their craft have been drastically reduced. According to reporting by Julian Meyrick in The Monthly, Monash, Murdoch, La Trobe, Charles Sturt and Newcastle universities have “effectively closed their standalone drama programs;” the drama departments at Flinders and Wollongong have seen cuts to teaching hours and staffing, respectively, while Queensland University of Technology and Federation University have seen class sizes increased.

A snapshot from drama at Flinders University demonstrates the flow of graduates into theatre, TV, and film as writers, presenters, comics, directors, designers, and actors, but importantly, also as founders of new performance groups across the genres of circus, music, youth theatre and more.

Graduates forge diverse paths. Take the careers of Marion Potts or Rachel Swain, both graduates of theatre and performance studies at the University of Sydney. Potts is currently CEO at Performing Lines, producing contemporary works by independent artists. Her executive producer role follows a stellar directing career with long stints at STC (1995-99), Bell Shakespeare (2005-2010), and Malthouse Theatre (2010-2015) and as director of theatre at the Australia Council.

By contrast, Swain’s unique career traverses multimedia and intercultural dance theatre. She co-founded innovative physical theatre company Stalker and is now co-artistic director of contemporary dance company Marrugeku .

From our experience, if you teach a student physical theatre they may end up making puppets, starting a theatre company, or acting in television. Teach community cultural development and they are equipped to apply “design thinking” to theatre making or social innovation.

University theatre departments have traditionally been a pathway to the professional schools of acting, directing, and design – VCA, NIDA, WAAPA – but graduates infiltrate all areas of the creative industries because of the broad skills and theory our contemporary departments teach. Importantly, they are also the future generation of teachers.

Vital young and emerging artists will suffer from cuts to these courses, and an increasingly dire funding situation when they do graduate. This will lead to a fracturing of the generational rejuvenation of the theatre.

Dire warnings for the future

In July, the Australia Institute’s Creativity in Crisis report estimated over 90% “of artists, creators and businesses” do not receive public funding and so were unable to access arts relief measures.

Many of these artists are freelancers: in theatre this may mean they move between jobs at the major state theatre companies, smaller funded shows, and independent, self-produced productions. Support for these artists is not only crucial for independent theatre, but extends all the way up the food chain.

Shadow arts minister Tony Burke estimated when JobKeeper ended, just one in five arts workers were receiving the payment.

A backstop for this pool of skilled workers, the Coronavirus Supplement Income, ended in April when the sector was rebooting. But renewed hard lockdown measures, first in NSW and then Victoria, have left these workers caught in a perfect storm.

For many freelance arts workers, prolonged interruption to their careers since March 2020 means a long absence from rehearsing, practising, collaborating and performing.

To avoid prolonged insecurity and precarity, many artists are establishing alternate income streams – often unconnected to their creative skills. It is likely many will exit the sector for good.

Touring in a new world

Touring – within Australia and internationally – greatly increases the number of people a work can reach, providing ongoing employment for artists and creative workers.

A national survey in late 2020 found the touring sector’s capacity was “stretched thin”.

Small independent theatre companies like Melbourne’s Ranters Theatre tour extensively. PC: AP Photo/Ranters Theatre, Anna Tregloan

Chris Bendall, the CEO of Critical Stages, a company that tours Australian productions, reports that during July and August, performances were deferred or cancelled “on a near-daily basis”. The expense was compounded by “uncertainty and anxiety as borders closed mid-flight,” lockdowns occurring while touring parties were finishing bump-ins just hours before showtime, and “travel plans were re-routed … to avoid artists being locked out of their own states or forced into 14 days quarantine.” Most cancelled shows were in regional areas.

This is just one report – small or large, urban festival centre or regional venue – it’s heartbreaking for everyone involved when the show can’t go on.

The long-term impacts of COVID-19 mean the same level of touring activity that happened before the pandemic cannot and will not resume. Future touring may well need to adopt new models such as hybrid live/digital delivery to increase audiences.

As part of this year’s Adelaide Fringe, for instance, performer Joanne Hartstone live-streamed her show The Reichstag is Burning to 38 countries via the new digital theatre platform, Black Box Live, she co-developed. In August, Hartstone again streamed her show live to the Hollywood Fringe and the Edinburgh Fringe festivals.

The COVID-induced pivot to live streaming by theatre companies and solo performers is at least giving rise to new skills development and the capacity for shows to be viewed live or on demand. Other post-COVID touring models include “slow touring,” where artists stay longer in a community to develop exchanges; and multiple casts to avoid border crossings. Both options are likely to incur higher expenses.

Julian Lewis, the artistic director and CEO of NORPA, a theatre company in Lismore, has called on all levels of government – local, state and federal – to develop policy supporting the complex, interconnected ecosystem of touring: those who produce, present, support and experience.

A broken ecosystem

In nature, as in the arts, biodiversity is a critical factor in maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Biodiversity is crucial to resilience. It helps ecosystems cope with stressors.

Entrenched neglect of the national performing arts ecology for nearly a decade has merely been compounded by the pandemic and inadequate emergency “lifelines”.

A raft of cultural policy recommendations from the Australia Institute includes: expanding funding to community art organisations and artists; rebuilding arts education in primary and secondary schools; reversing Commonwealth funding cuts to university creative arts, media, and humanities courses; and greatly expanding the number of three-year creative fellowships on offer from around 10 per annum to 300 per annum – mirroring the Australian Research Council’s annual fellowships for researchers.

For theatre this could mean a reset of once-in-a-lifetime magnitude. Improving working conditions for artists, strengthening the flow of new and emerging artists, and taking more theatre to regional and diverse communities.

It shouldn’t be a wishlist. It’s an opportunity to protect and grow our unique theatre culture.

This article was originally posted on theconversation.com on October 7, 2021, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Gillian Arrighi and Clare Irvine .

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.