An imaginary trip with the god of dance

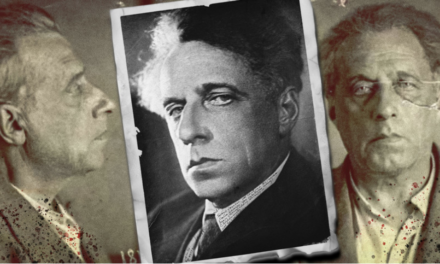

While he was often called le dieu de la danse, Vaslav Nijinsky was a god who fell hard from his towering cloud. In the early twentieth century, Nijinsky became a star dancer (and eventually a choreographer, too) with the pioneering Ballets Russes in Paris, led by Sergei Diaghilev. His career there was as short as it was legendary. The story of that steep climb and downward fall is compellingly evoked in FLY, the new performance by choreographer, dancer, and filmmaker Sidney Leoni.

Leoni’s FLY is based on Nijinsky’s diary, which offers a bewildering account of an artist sinking into psychosis and schizophrenia. The spectacular jumps for which Nijinsky became famous as a dancer also mark his diary, as the text makes flighty leaps between biographical anecdotes, delusionary associations, and wild reflections on the world around him. Combining film and dance, FLY takes us on an imaginary trip through Nijinsky’s flipping mind, rather than sticking to the constraints of a historically accurate biography. As we fly with Nijinsky on his cloud, we also descend with him into the abyss.

FLY mainly testifies to Sidney Leoni’s background and talent as a filmmaker. Throughout the performance, we see a slightly adapted version of Leoni’s feature film about Nijinsky, I AM ALMOST NOT MAD, released in 2022. While the four dancers in FLY (Philip Berlin, Linda Blomqvist, Dolores Hulan, and Sidney Leoni) perform in front of a stage-wide screen choreographic sequences loosely related to the filmic images, it is primarily the movie that draws us into Nijinsky’s story. Only a few minutes into the performance, an unexpected and dazzling montage with the allure of a Baz Luhrmann film combines at a staggering speed war images with miniature models of theatre sets, magnified faces, or even Yves Klein jumping out of the frame of his own photograph, Leap into the Void. This absurdist overture, clearly intended as a kind of telematic time machine, pulls us right into Nijinsky’s sometimes hallucinatory world.

The speedy yet stunning beginning of FLY soon gives way to a more measured narrative that, through dialogue and voiceovers, seeks to inform spectators on Vaslav Nijinsky’s complex but intriguing life story. For even though Leoni did not want to make a biopic, we do get a fairly complete picture of Nijinsky’s turbulent biography. We get to know how Nijinsky’s professional and also amorous relationship with Diaghilev rather quickly crumbled apart, to the point that he married the insidious Romola de Pulszky and became entangled in a web of various intrigues and interests, with Romola’s mother, Emília Márkus (portrayed in the film by Christine De Smedt), playing a quite significant role in this. We also learn how Nijinsky had a formative influence on his younger sister, Bronislava Nijinska, who was a dancer, too. FLY complements this already incendiary ensemble by adding one fictional character, Paul Chaplin, who is introduced as a French dancer to whom Nijinsky feels attracted.

The many biographical facts sprinkled across FLY primarily provide a general framework for a more capricious, non-chronological dive into Nijinsky’s mind. Rapid jumps in time sometimes lead to fabulous scenes featuring, for example, faun-like figures sensuously wrapping themselves around each other. Allusions like these turn FLY into an echo chamber of numerous resonating references to Nijinsky’s own, often notoriously, famous choreographies, such as L’après-midi d’un faune (1912), Jeux (1913), or Le sacre du printemps (1913). While this deliberately fragmentary revisitation of Nijinsky’s oeuvre is part of the poetic universe Leoni wants to create, the downside is that the specificity of Nijinsky’s choreographic innovations is not always accounted for.

With FLY, Sidney Leoni joins a growing genre of “documentary dance” that delves into various intermedial crossovers between film and live choreography to revisit an iconic part of dance history.

Because of this clear preference for poetic evocation over factual biography, FLY resembles another cinematic translation of Nijinsky’s diaries, the film The Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky (2001) by director Paul Cox. Like Leoni, Cox was not interested in offering a historically accurate account, but rather what he called a “cinematic poem,” which likewise takes the necessary liberty in terms of chronology or characters while alternating dance scenes with fairy-like images of nature. Nonetheless, the slower pace and at times somewhat didactic tone of Cox’s film contrasts sharply with the snappy and vertiginous rhythm of Leoni’s work.

In terms of its themes, too, Leoni made some distinct choices in FLY, by strongly highlighting, for example, the role of World War I or the ecological interests that became increasingly important to Nijinsky. These topics obviously resonate with our contemporary concerns, when the war in Ukraine is severely disrupting global politics while the climate crisis, also, leads to various ecological disasters, succeeding each other ever more rapidly. Indeed, as we can read in the press file, Leoni wanted to express, through the figure of Nijinsky, an increasing existential fear that he personally is experiencing in the face of our current world.

DANCING THE WAR

As he calls FLY a “film-dance-performance,” Leoni wants to explore how the characters on screen can either reinforce or counteract the dancers on stage. This strong bond between film and dance becomes most obvious in how the four dancers on stage switch between portraying the ensemble of the Ballets Russes and the four main characters we also get to know in the movie: Vaslav Nijinsky, Paul Chaplin, Bronislava Nijinska, and Romola de Pulszky. An ingenious light design literally highlights this overflowing of the screen onto the stage as color patterns and motifs from the film are repeated on the floor.

PC: Åsa Lundén

PC: Åsa Lundén

PC: Åsa Lundén

Yet it is precisely in the cross-connection between dance and film where FLY is sometimes at its weakest: because the film is so absorbing, we are primarily drawn to what is happening on the screen, while the actual dancing happening on stage sometimes seems like an additional side-effect. It is a difficult task for the dancers to claim their own place within the overall setup of the piece, given that the film makes a strong demand on our attention by switching rapidly between different episodes from Nijinsky’s life or by presenting us with overwhelming poetic images. The implicit potential of this setup emerges most clearly when the dancers interact directly with the screen. When the film shows a rehearsal for one of Nijinsky’s choreographies, for example, the dancers use their shadows to form dark silhouettes that, because they stand out sharply against the light of the immense screen, seem to duplicate the film characters.

Most memorable in this regard is the scene based on the last dance Nijinsky would ever perform. On January 19, 1919, Nijinsky gave a private performance at a hotel in Saint Moritz, Switzerland, which he began with the legendary words, “Now I will dance you the war…the war which you did not prevent.” The film in FLY only shows the distraught faces of those present, while Sidney Leoni performs the choreography on stage. Like Nijinsky, he uses two pieces of rolled up fabric in black and white, with which he forms a cross. It was on that same day that Nijinsky would begin his diary. Six weeks later, he was for the first time taken to a psychiatric hospital.

With FLY, Sidney Leoni joins a growing genre of “documentary dance” that delves into various intermedial crossovers between film and live choreography to revisit an iconic part of dance history. Because of this interest, Leoni’s FLY can be aligned with the work of choreographers such as Olga de Soto, Josep Caballero García, and, to some extent, Michiel Vandevelde. What sets Leoni’s FLY apart, however, is the care (and financial investment) that his film on Nijinsky clearly required. He resolutely opts for a sophisticated full-feature film that devotes much attention to costumes, set design, editing, etc. Perhaps not coincidentally, I AM ALMOST NOT MAD won the award for “Best International Feature Film” at the Polish International Film Festival.

At the same time, Leoni’s work also differs from other types of documentary dance developed by choreographers such as Arkadi Zaides, Rabih Mroué, or Zoë Demoustier. Their performances rather focus on socio-political realities that, strictly speaking, take place outside the realm of the arts. Remarkably enough, Leoni, too, does manage to get his own societal disquiet into the theatre, as he uses Nijinsky’s story to give his audience a push in the back to remind them that no choreographer, even if declared insane by some, can ever cut himself loose from reality.

This article was originally posted on e-tcetera.be on April 18, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Timmy De Laet.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.