What is the transformative potential of party performances?

Since venues reopened after the – hopefully – last lockdown, going to the theatre has become, more than ever, a festive event. Theatre makers are increasingly staging party scenes or working with music and choreography; sometimes theatre halls even transform into clubs, and queerness takes centre stage. Offstage, too, festivals and theatre houses are now regularly using parties to seduce a (new) audience. “About last night”, Kristof van Baarle asks himself: what does this trend have to offer to the theatre?

Sometimes you just start writing at the wrong time. Like when you try to tackle an essay on parties and performances in the days following Christmas and New Year. Yet maybe “the day after” is as much a part of the party as the music and dancing are. You plant yourself on the sofa. Perhaps the music you have playing in the background makes a half-hearted attempt to get you back into yesterday’s mood. Perhaps you’re scrolling through e-mails and other messages waiting to be answered. Waking up takes a little longer than usual, and as you think back to the day before, you hesitate between fond recollections and sober reflections: was that all really necessary?

In this text, which I wrote after attending several parties-as-performances and performances-as-parties, I want to adopt the same dual perspective of fondness and soberness. There is something undeniably seductive about performances that present themselves as parties, or that stage certain aspects of nightlife. After two long years of lockdown, a night out to the theatre feels all the more like a cause for celebration.

“Despite the omnipresence of social media and Zoom, being alive is about more than being observed by cameras and apps. Sharing the same physical space and being able to smell and feel each other’s presence: that’s what it’s all about.”

In addition, not only artists, but also theatre houses and festivals such as CAMPO, Bâtard and Kunstenfestivaldesarts (to name some Belgian examples) are focusing on nightlife again – often to reach new audiences, but hopefully also to add a deeper meaning to the word ‘festival’ as an alternative space and time that runs parallel to the everyday world. Last autumn, both Horst Arts and Music Festival and Decoratelier even devoted symposia and workshops to nightclub scenography, sound, and safety.

At the same time, a critical attitude is required, because such ‘party performances’ often claim to say something about certain communities, about the times we live in, or about the time and space of theatre itself and the role it can play in our society. And they don’t always do so with the same level of insight or sharpness. How do we deal with this festivity in the theatre, and what might it mean? What is its potential to change a person’s life, “when the party is over”?

First, something about ‘our time’. Whether explicitly or implicitly, the corona pandemic was an important context for several of the party performances staged last year. The lockdowns; their crippling effect on social life; the accelerated digitisation of work, friendship and love; the presence of death in our everyday lives; and the fear of touch, closeness and togetherness have no doubt left deep wounds. Our longing for the other, the fact that we can only become ourselves in relation to others, has seldom been so tangible. Social bubbles and curfews did create a different kind of intimacy, though, as well as introducing new ways to spend our free time. Having fun, partying, dancing, singing …: all those activities were scaled down or went underground, and engaging in them meant risking heavy fines, social disapproval, and other forms of punishment.

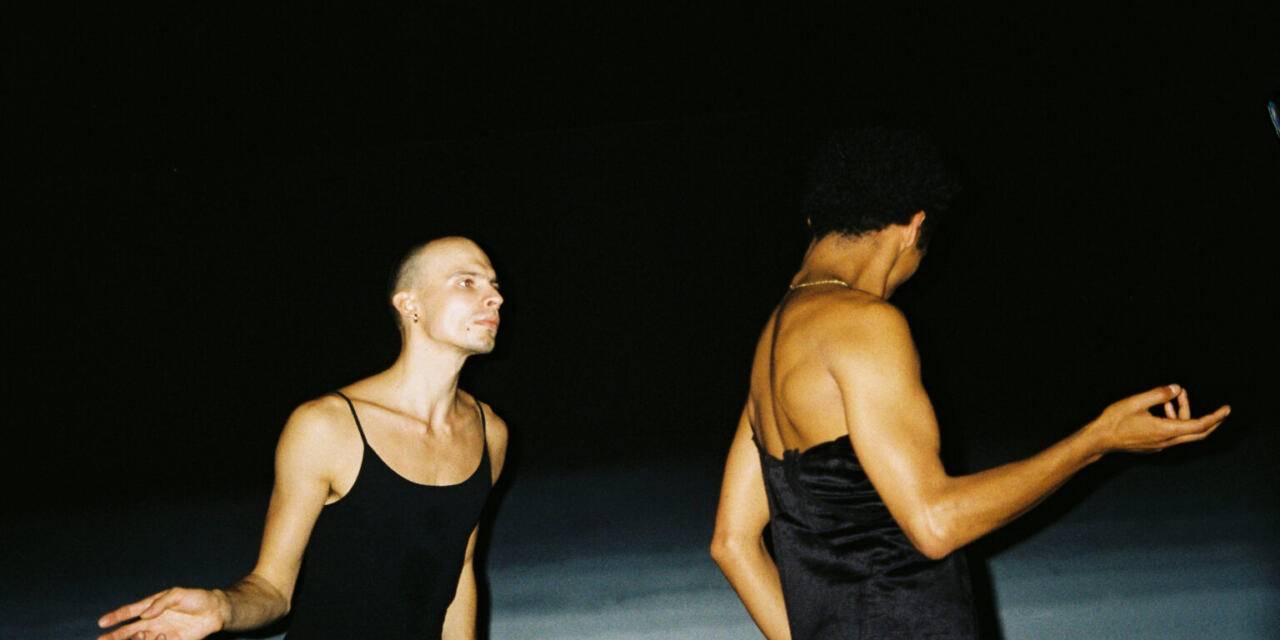

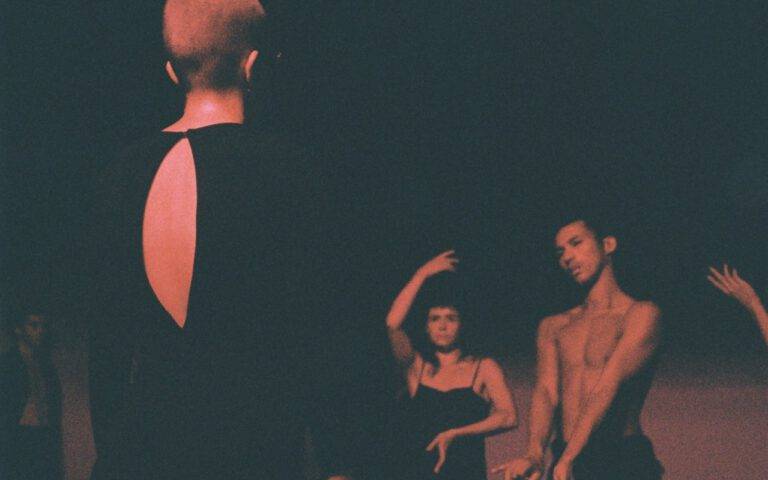

Untitled (Holding Horizon). Alex Baczynski-Jenkins.

Even regardless of morality and responsibility (which I don’t want to go into here to avoid judging or inviting judgment), there are several relevant observations to be made about the phenomenon of the lockdown party. It emphasises the potential intimacy of a party and the sense of belonging it can temporarily create, and it reveals the urgent need that many feel to be together, to dance and listen to music – alcohol and drugs are optional here, I think. But what such secret parties gain in intimacy, they lose in sociality: these are invisible gatherings, the opposite of going out in public. Putting yourself out there and watching others: that’s what we’re after, too, and this might well be the strongest driver behind the so-called “revenge partying”. Despite the omnipresence of social media and Zoom, being alive is about more than being observed by cameras and apps. Sharing the same physical space and being able to smell and feel each other’s presence: that’s what it’s all about.

This context is helpful to understand an evening like Nachtzwemmen (night swimming), conceptualised by Lieselot Siddiki and Jarne Van Loon. These two drama students had been forced to spend most of their time at KASK, Ghent, under corona conditions. Nachtzwemmen is a kind of nightlife revue that brings together all the things so many young people missed out on: the excess of going out, the memorable encounters and individuals, the eroticism, the sex, the energy you get from music and from dancing together. Given the young age of the makers, one could even wonder if their project might be an expression of something that should have happened offstage but couldn’t: namely, the discovery of nightlife. From that perspective, the performance becomes a projection of expectations created by stories, films, TV series, social media and so on. All that pent-up social and physical energy erupts – chaotically, with no restraints – and even the Deliveroo driver is invited to the party, or gets caught up in it.

Even though it’s a clear sign of the times, the performance does have some flaws. But that’s not the point here: Nachtzwemmen contains elements that emerge in other performances as well, and that therefore deserve a closer look. Its unbridled energy is characteristic of what performance theorist Jill Dolan has labelled ‘a dramaturgy of desire’. For even more than staging a party, Nachtzwemmen shows a desire for a party as a time and space of togetherness, community, and self-expression. However, the performance itself doesn’t really make the critical distinction between ‘being’ a party and longing for one. After all, the performance is not a ‘real’ party; it remains a representation of a party, a fantasy that oh-so-very-badly wants to become real – which it did, in fact, when Siddiki and Van Loon organised the CAMPO Party called A Shot at Love.

Queerness as a horizon of possibilities

With drag, bondage, and other references, Nachtzwemmen draws heavily on elements stemming from LGBTQIA+ nightlife. The combination of queerness and the underground club scene is also the main focus of Alex Baczynski-Jenkins’ Untitled (Holding Horizon). In this four-hour performance, a group of dancers moves together through the encroaching darkness, in various formations based on the box step. The movements that are reminiscent of vogueing, together with the dancers’ gender fluid outfits and bodies, turn Untitled (Holding Horizon) into a timeless queer club, a space where bodies can briefly find each other and move to the same beat.

“Queer has become a theme, a label that cultural centres like to use to tie certain programme lines together and appeal to a specific audience.”

While Nachtzwemmen was a performance of longing for partying and for the night, in Baczynski-Jenkins’ work, the longing is more of a political quest. Knowing that the choreographer is part Polish, and that Poland has established LGBTQ-free zones in recent years, you realise that it becomes a political gesture to have people of any gender expression or sexual orientation perform in an underground space where they can get together and have fun.

There’s also a deeper political potential to this durational performance. It happens all too often that queerness as such is regarded as a political statement, that visibility is automatically considered a good thing, or that a queer venue or work turns its back on the rest of the world out of a desire for a safe space. But what is queerness exactly? Is this term, which originated from the critical and performance theory of the 1990s and 2000s, subject to inflation and devaluation now that it has been thrown around at every opportunity in mainstream contexts for several years? If we really cherish a term, we better use it sparingly and with nuance.

The low-key aesthetic of Untitled (Holding Horizon) leaves room for exactly that – for being precise, for understanding queerness in a more nuanced way. The idea of a ‘queer identity’ is practically an oxymoron. Like masculinity and femininity are categories that are performed but never ‘perfectly’ executed, queerness is a horizon: a constant process of disrupting and twisting, again and again, of wanting to be out of line and thus deliberately slipping between the cracks of the bourgeoisie. From this perspective, the ‘mainstreaming’ of ‘queering’ performance art forms such as drag or vogue leads to a complicated situation. If this thought occurs to me even when attending certain performances at the theatre – like Jaouad Alloul’s Venus in Libra or Atropa by Naomi Velissariou and Floor Houwink ten Cate – then it’s even more dominant while watching Netflix series like Pose or any of the obligatory queer side-stories in just about every film or show on that (and other) streaming platforms. On the one hand, this is a victory for the acceptance of various ways of living, loving, and expressing oneself; on the other, it threatens to take away their disruptive potential.

“Another interesting clash between theory and life-practice: you can be exploring the darkest and most depressing topics, and still go through life quite cheerfully.”

The clumsiness that tends to creep into the communication about evenings and performances exclusively for people of colour – whether or not at the intersection of LGBTQ gender experience – testifies to the constant search that the performance arts are undertaking when it comes to the nexus of social justice and identity. Queer has become a theme, a label that arts centres like to use to tie certain programme lines together and appeal to a specific audience. This attempt to achieve more inclusive programming is well-meant but it threatens to turn ‘queer’ into a catch-all term that loses its meaning and that reduces the work of a wide range of artists to a kind of freak show.

Untitled (Holding Horizon), on the contrary, is an excellent example of performance theorist José Muñoz’s view that a queer aesthetic charts a path towards future social relations. It’s always about a ‘not yet’, about an ideal image, about a potentiality that is performed in the hopes of sparking an imagination for other futures. So, the deeper political potential lies precisely in the ‘not yet’ of Baczynski-Jenkins’ work. Just like Nachtzwemmen is not a real party, but rather shows a desire for it, Untitled (Holding Horizon) is about keeping a horizon alive in which we can coexist differently, in which lives can take other forms. The nightclub, as a prime symbol of the underground scene, is the place par excellence for this, then. Bodies find each other in bars, clubs, cruising spots – in the dark, accompanied by house beats and minimal techno. This secluded party, whose duration and endurance make it amply clear that it’s not just a random gathering, holds up a dark mirror to the splendid, public, and increasingly commercialised Prides. Are the seeds for a bigger parade being sown here, or are we witnessing a return to queerness’s disruptive core instead, away from commerce and stereotypes?

You could read this performance in the light of what philosopher Judith Butler described in her Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Assemblies, she writes, “strive for modes of life in which performative acts struggle against precarity, a struggle that opens up a future in which we might live in new social modes of existence, sometimes on the critical edge of the recognizable, and sometimes in the limelight of the dominant media – but in either case, or in the spectrum between, there is a collective acting without a pre-established collective subject; rather the ‘we’ is enacted by the assembly of bodies, plural, persisting, acting, and laying claim to a public sphere by which one has been abandoned.” Butler is referring mainly to protest movements, but I think protests can take on other forms than people flocking to the streets. There are many kinds of ‘performative acts’, not only in streets and on squares, but also in semi-public or less mediatised and visible spaces where people come together, like in the darkness of a club or theatre.

Another element that resonates with and in the party performances is the utopian search for new social forms of life. The more nuanced works that waver between visibility and invisibility, such as Baczynski-Jenkins’, make it clear that the struggle might be with the sense of community an sich, and not just for LGBTQ communities. What gets abandoned in times of mediatised and polemical neoliberalism is the social itself. So, it’s about more than ‘queerness for queerness’ sake. After all, a space where bodies can find each other, and where a ‘we’ can unfold that is not predetermined, is more universal than that.

Untitled (Holding Horizon). Alex Baczynski-Jenkins.

This means that, despite its underground vibe, Untitled (Holding Horizon) does not emit an air of exclusivity. Quite the contrary: the choreography feels open and inviting, creating a space where you can be at ease, lie down, nod along, and be submerged in the atmosphere created by the music and the light. But as Muñoz also knows, we must keep in mind that queerness, like any utopia, is doomed to fail. Hints of unhappiness and desperate courage shine through in Untitled (Holding Horizon) and, to a lesser extent, in Nachtzwemmen. Baczynski-Jenkins seems conscious of the fact that Untitled (Holding Horizon) remains a performance, a horizon, a theoretical future that opens up for the duration of the performance – in that respect, four hours is actually a very generous amount of time – and is closed off again afterwards. The clean, simple form, the constant semi-darkness, the box step choreography that keeps going without a moment’s rest: all of it suggests that we’re witnessing something that cannot or will not yet move into the light, and therefore keeps shimmering on the horizon. Using the walls of the theatre to create a situation of exception is thus a prerequisite for seeking that political, social potential and for conjuring up a utopia. But being walled off, it remains by definition finite as well as ‘utopian’ in the sense of unreal.

“A festival doesn’t have to be only about fun, dancing, drinking, or eating. It can also contain moments of stillness and contemplation.”

A paradox, or at least an inescapable aspect of party performances, then, is the relationship between utopia and reality. How do you align the status of an isolated performance (‘isolated’ in the sense that it shares something with the audience for a certain time and in a certain space) with a broader social reality? Does portraying a community in party mode automatically support its emancipation or liberation? The fact that the performance is utopian makes it a bit theoretical, as opposed to the actual practice of life. Perhaps this brings us back to that age-old question of the politics of theatre. Talking about utopian performances and parties, Jill Dolan wrote that the sense of utopia is not distributed evenly across the whole evening or night, but rather presents itself as a flash in which you feel the possibility of a complete turnaround. In a similar vein, I can’t help but feel that, just like in Untitled (Holding Horizon), the political cannot be found so much on the surface of the represented partying communities as in a fundamental sense of belonging, of a possible social connection. After all, that connection seems to be more damaged than we sometimes think. How can we imagine the relation between theory and practice, between performance and life, between the club and the day after? In the case of party performances and their focus on fun and togetherness, this resonates with the discussion of the relationship between theory and practice.

The truth is concrete

In 1985, after 20 years of research on ecology and the conservation of natural habitats, the Australian ecofeminist Val Plumwood was attacked by a crocodile during a canoe trip. Dragged into what is called ‘the death roll’, Plumwood suddenly felt theory and practice coming very close together. The attack served as a violent confirmation of her thinking about the power of nature and the state of denial in which we live in the West. Plumwood survived the fight and, thinking back to it later, wrote that ‘in the moment of truth, abstract knowledge becomes concrete’. As an analytical philosopher and activist, she had built an almost irrefutable philosophical case against the Western objectification of nature and in favour of a greater appreciation of ecological connections (years before Donna Haraway did, by the way). But Plumwood’s theoretical knowledge had not prevented her from making a life-threatening mistake when she entered crocodile territory on that fateful day, just as the rainy season was starting and the crocs would be surfacing more frequently to hunt for prey.

How, specifically, did a thorough critique of Plato’s idealism help a person in the 20th century to rethink their ethics in an ecological way and to move thoughtfully through natural reserves? Plumwood wrote how she suddenly found herself face to face with her own framework of values, thinking ‘surely this could not be happening. I am a human being, not food for an animal’. From then on, her writing takes a completely different turn, starting less from theory and more from stories and lived knowledge. In times of truth, abstract knowledge becomes concrete, or in other words: theory comes under pressure. Plumwood beautifully describes how, after years of research and fieldwork, you think you know a thing or two, but in a real confrontation with your object, you realise you actually don’t. And that doesn’t have to be a problem. Not-knowing remains a valuable attitude for theatre scholars and critics, too, when they look at their object: performances.

I had a similar – but certainly not a comparable – experience during the first lockdown in 2020. Researching the impact of technology on society and on forms of end-times, I suddenly ended up living the reality that the theorists I was studying had been warning against all along. Apart from becoming disoriented and jaded like so many others, I found that thinking about the situation became almost impossible. It was a waiting game. Giorgio Agamben, the philosopher who has been pivotal in shaping my worldview and who has been sounding the alarm about totalitarian tendencies in democratic states for decades, found his predictions confirmed to such a degree that he had no choice but to oppose both the state of emergency that had been declared and the government measures that were crippling society. While such a dissident voice was and still is necessary, it left little room for a constructive vision on how to live in pandemic times. It also paid little attention to the possibilities that surfaced (or rather: were forced to the surface). As a sidenote: it was surprising to see so many self-proclaimed critical thinkers immediately reject Agamben’s assessment of the situation and, in a time of ‘emergency’, meekly and blindly follow the state they are otherwise so keen to deconstruct.

Another interesting clash between theory and life-practice comes into view from a different perspective. Namely: you can be exploring the darkest and most depressing topics, and still go through life quite cheerfully. You can be aware that actions, protests, or marches are likely to be pointless, and yet continue to invest all your energy in that battle. Perhaps not surprisingly, it was a cultural philosopher and activist who had something meaningful to say about this tension between theory and practice – or, if you like, between content and form. In his book Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi wrote that “ despair is the only appropriate intellectual stance in this time. But I also think that despair and joy are not irreconcilable, as despair is the mood of the intellectual mind, while joy is the mood of the embodied mind. Friendship is the force that transforms despair into joy.”

Untitled (Holding Horizon) . Alex Baczynski-Jenkins.

In other words: joy and friendship are important remedies when dealing with despair and negativity. If we take Berardi’s somewhat simplistic body-mind dualism a step further, we could say that you can be ‘desperate’ in theory, but ‘full of joy’ in practice. It’s not always easy to reconcile the two. Conversely, a joyful performance can also originate in sadness and pessimism. This opens up a different perspective on the party performances and discussed above. They draw on a lack, on a desire to perform the opposite, thereby adding a critical potential to joy. These party pieces are explicit examples of a broader dynamic that can be observed in works that deal with rather heavy themes, but that do radiate a sense of joy in their performativity, in the collaboration and the creation process.

Rituals of life

In his booklet on the disappearance of rituals as symbolic, repeated, situated and meaningful performances that contribute to community building, the German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han talks about the role of festivals. Rituals were and often still are a part of festivals, which he sees as festive suspensions of the everyday. But in times of self-exhausting narcissism, Han argues, rituals – especially in the West – have lost quite a bit of social power. At most, we briefly press pause on the everyday; we enjoy some free time or practice mindfulness, but we do this mainly so we can stay in the productive rat race. Regular moments of non-work in which communities can grow and be nurtured are scarce.

The need to repeat a ‘useless’ ritual or a party in order to tie the idea of a community to the practice of communal living, sheds a different light on the (self-)accusation of ‘preaching to the choir’ that is so omnipresent in the cultural sector. Jill Dolan, too, knew that a utopian horizon must be repeated over and over again to keep the communities around it glued together – however fluid they may be.

Hence Han’s plea for a search for a new place for rituals and for a reappraisal of festivals as a ‘surplus of life’ rather than a convenient marketing trick to promote things as an event. A festival doesn’t have to be only about fun, dancing, drinking, or eating. It can also contain moments of stillness and contemplation. This critical side of festivals is also reflected in works like Baczynski-Jenkins’. Judging by the amount of time Untitled (Holding Horizon) takes up, it is not about overstimulating the audience, but rather about creating an atmosphere in which the festive and the meditative come together.

Analogous to Plumwood’ and Berardi’s statements on the relationship between knowledge/theory/intellect and the concrete/practice/body, Han argues that “life reaches a true intensity at the very moment the vita activa (which in its late modern crisis degenerates into hyperactivity) incorporates the vita contemplativa”. This is perhaps the crux of the matter of last year’s party performances: parties, festivals and performances are moments when shared pleasure becomes, time and again, a source of energy, so we can muster the desperate courage to keep looking at utopian horizons.

Does this mean that all thinkers should hit the dance floor? Or that, as Pozzo so characteristically put it in Waiting for Godot, it’s about “dance first, think later”? Perhaps it is more about a relentless commitment to a practice, to keep looking, to keep establishing and strengthening connections. A party in and of itself doesn’t build a friendship or kinship. We need to rehearse that, too. “Let’s do that again, the director says. Thinking does not come easily to the body.” (Alain Badiou, Ode aan de liefde (Ode to love)).

This article appeared on Etcetera on April 27, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

Written by Kristof van Baarle, translated by Lies Xhonneux.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Meg Hands.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.