Polish classical musicians and opera singers have always enjoyed global renown, with singers such as Mariusz Kwiecień, Ewa Podleś, Piotr Beczała, Aleksandra Kurzak, and Andrzej Dobber regularly performing at the world’s top opera houses. Likewise, Polish opera directors have been successful abroad—most recently Mariusz Treliński in his Met debut with Bluebeard’s Castle and Iolanta. Poland’s own operas, however, have largely remained a mystery to opera lovers worldwide. The Adam Mickiewicz Institute in Warsaw—founded in 2000 by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage in consensus with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with the sole mission “to establish Poland as a crucial link in the international circuit of ideas, values and cultural goods of the highest calibre”—aims to change this (“Mission Statement”).

One of the Institute’s most recent and most successful projects is a production of the little-known Polish opera The Passenger (“Passazhierka” in Russian; “Die Passagierin” in German, or “The Woman on the Ship”), composed in 1968 by the Polish-Jewish composer Mieczysław Weinberg (1919–96) with a libretto by the Russian music critic Alexander Medvedev, based on the 1961 autobiographical novel of the same title by Zofia Posmysz. In 1968 the opera began rehearsals at the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre, but for a number of reasons, the performance never materialized. Weinberg died in 1996 without ever seeing it staged. It took forty years after it was written for the opera to get its world premiere, in 2006, in a concert performance at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich Danchenko Music Theater in Moscow. The British opera director David Pountney (1947–) became interested in it after receiving the promotional materials from that very concert version.

In 2010 the opera, directed by Pountney, who also prepared the English translation of the libretto, was seen for the first time ever fully staged at the Bregenz Festival in Austria. Spearheaded by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, it was a coproduction between four major European art institutions: the Bregenz Festival, the Wielki Teatr in Warsaw, the English National Opera in London, and the Teatro Real in Madrid. In 2010, right after its premiere in Austria, the opera was shown in Warsaw, and it was performed a year later, in 2011, at the English National Opera (broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 on the 15th of October). In 2013 it was presented by Badisches Staatstheater in Karlsruhe. The Houston Grand Opera staged that same production in January 2014 for its American premiere. In 2014 it was presented at the Armory at the Lincoln Center Festival (where I had a chance to see it).

This spring the production is scheduled to be shown at the Chicago Lyric Opera. A smashing success, drawing a slew of glowing reviews from both European and American opera critics, Weinberg’s opera, its context, and libretto (originally written in German, English, Polish, Yiddish, French, Russian, and Czech), is not only a complicated work of art, it is also a complicated work of historical trauma.

Weinberg’s parents and sister perished in the Holocaust at the Trawniki concentration camp, about 40 kilometers southeast of Lublin (not too far from the Russian border). Weinberg himself managed to escape Warsaw on foot at the start of the war in 1939 as the Germans’ heavy artillery began pounding the city. He ended up in Soviet Russia, where he met the composer Dimitri Shostakovich. Thirteen years his senior, Shostakovich became Weinberg’s mentor and his strongest influence. The score for The Passenger, in fact, shows some of Shostakovich’s sway with Weinberg’s work, including, as Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times noted: “Neo-Classical structures and a harmonic voice ranging from a dissonance-charged diatonic idiom to near-tonal modernism.”

In 1942, while in Russia, Weinberg married Nataliya Vovsi Mikhoels, the daughter of the Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels, who was killed in 1948 on Stalin’s order. At the height of the Stalinist terror, Russian composers who didn’t follow the official party line (these included Weinberg and Shostakovich) were repeatedly attacked and arrested. In early 1953 Weinberg himself spent a few months in prison following the notorious Doctors’ Plot. Seen as Mikhoel’s son-in-law, and therefore under suspicion, Weinberg was accused of expressing “Jewish bourgeois nationalism” through his works (Fay 182). Reportedly, during the interrogation, he once asked, ironically: “Since I don’t know a single letter of Yiddish but own two thousand books in Polish, shouldn’t that be Polish bourgeois nationalism?” (Groover). Fortunately, Stalin died the same year, and most political prisoners, including Weinberg, were released. Considering Weinberg’s personal history with anti-Semitism, his interest in a book like Zofia Posmysz’s, which is based on her own experience in Auschwitz, should come as no surprise, but it was Shostakovich who, knowing his younger protégé’s painful past, brought Posmysz’s novel to Weinberg’s attention. It was also Shostakovich who introduced Weinberg to Alexander Medvedev, who would later write the libretto.

Mieczysław Weinberg with Russian director Kirill Konrachine and Mrs Kondrachine in an undated photo. A sign behind them announces Music Songbooks Books. Press photo

Weinberg was a prolific composer, authoring altogether 20 numbered symphonies (not counting his chamber symphonies and sinfoniettas); 17 string quartets; a raft of concerti, sonatas, and film scores; and seven operas. Like The Passenger, many of his other works also include Jewish themes or allude in one way or another to the Holocaust, starting with Jewish Songs after Shmuel Halkin (1944), and ending, most famously, with Symphony No. 21, subtitled “Kaddish,” composed in the early 1990s and dedicated to the “victims of the Warsaw Ghetto.” Weinberg’s monumental Eighth Symphony (1964), subtitled “The Flowers of Poland,” which was set to the poem “Kwiaty polskie” (the “Polish Flowers”) by the Polish-Jewish poet Julian Tuwim, is also a tribute to Poland; it’s a work of trauma, which mourns the destruction of Weinberg’s homeland by the Nazis. Writing about the Holocaust motifs in Weinberg’s work, David Pountney suggested that this “composition would become an act of atonement: why else, of his family, had he alone been allowed to survive?” In a 1965 interview about the symphony, Weinberg said: “In the war, my entire family was murdered by Hitler’s executioners. For many years I wanted to write a work in which all the events would be reflected . . . the horrors of war, and at the same time the deep faith of the poet in the victory of freedom, justice and humanism” (qtd. in Ivry). The same themes and artistic goals that illuminate the Eighth Symphony would reappear in The Passenger, which Weinberg began working on only two years later. Weinberg himself considered the opera his most important work, and Shostakovich called it his “masterpiece” (“Holocaust Tale”).

The Passenger is based on the 1961 novel by Zofia Posmysz, which depicts her own experiences as an Auschwitz prisoner. The novel was inspired by a 1959 incident on board the Place de la Concorde when, while travelling, Posmysz overheard a German tourist calling out in what seemed a familiar voice. The terror she felt at the thought that she could be faced with her former tormentor prompted Posmysz to try to imagine the situation from the other side, that of the Auschwitz guard who tortured her. In 1959 Posmysz wrote a radio play, Passenger in Cabin 45 (directed by Jerzy Rakowiecki, with Aleksandra Śląska and Jan Świderski), and in 1960, a TV novella, The Passenger (directed by Andrzej Munk, and starring Ryszarda Hanin, Zofia Mrozowska, and Edward Dziewoński), with similar plots about two women, a former guard and a prisoner, travelling on the same ocean liner years after the war ended. Shortly after, Posmysz and Andrzej Munk wrote a screenplay together for the movie version, The Passenger, which was released unfinished after Monk’s death in a car accident in 1961. In 1962 Posmysz released the book version of the story. Weinberg’s opera is based on that book.

In the novel, Annaliese “Liese” Kretschmer, a middle-aged German woman, is travelling aboard an ocean liner with her husband, Walter, from Hamburg to Rio De Janeiro, where he has been offered a diplomatic post. While on the ship, Liese and Walter enjoy themselves and look forward to their new life in Brazil. Walter talks to an American journalist who was one of the soldiers liberating the Dachau concentration camp. Sixteen years after the war’s end, the journalist is concerned about what he perceives as a lack of remorse in the German people, particularly so as Walter is trying to justify and explain Germany’s ignoble history. Suddenly Liese sees a mysterious woman who could be Marta, a Polish inmate at the Auschwitz concentration camp where Liese worked as an SS overseer. Liese’s husband knows nothing of her grisly past, and he is shocked. For one thing, Liese’s past could destroy his diplomatic career, but more so, he himself is outraged, because he did everything he could during the war to avoid being part of the Nazis’ death machine. Liese, on the other hand, admits that she believed in Nazi ideology, but she doesn’t feel guilty or responsible for any of the crimes. She explains that she treated the prisoners well and participated in the gas chamber selection process only once, under her commander’s orders. Liese claims that she chose Marta as her favorite, saved her life a few times, and even made it possible for Marta to meet up with her fiancé, Tadeusz, a prisoner in the male ward—all of this in hopes of using Marta to control other inmates. Perhaps now, grateful Marta would testify on Liese’s behalf if ever need be?

The story moves back and forth between Liese and Walter’s conversation and scenes in the concentration camp. Eventually, as the camp storyline progresses, Liese discovers that Marta only pretended to collaborate with her while at the same time organising resistance among the prisoners. Determined, Liese decides to either break her or turn her into a true collaborator. She proceeds with calculated cruelty to manipulate Marta into submission, which includes getting Tadeusz killed. When Liese receives an offer of a transfer to another camp in Germany, she wants to take Marta with her, but Marta refuses. Transferring would mean leaving her campmates behind, and she can’t do that. On the boat, Walter and Liese figure that the mysterious woman is indeed Marta and that she might have recognised Liese. Walter decides that it would be best for Liese to disembark in Lisbon and travel to Brazil by plane, but before Liese disembarks, the mystery woman leaves the boat, passing by Liese without a word and leaving her forever in suspense.

The power of Posmysz’s novel lies in its intimacy: neither Liese nor Marta is a generic stand-in for larger historical narratives; they are foremost two women caught in a personal power struggle. The horror of their story comes through its specificity: the minuscule details that puncture their every move and gesture. Andrzej Munk’s movie, co-written by Posmysz, captures the essence of that struggle, with black and white chiaroscuro shots and long, slow, silent camera movements. Together with Andrzej Wajda and Roman Polański, Munk belongs to the so-called Polish Film School, the style of 1950–1960’s Polish filmmaking that grew out of war trauma and as a response to socialist realism: the fewer words, the better, as ambiguity leaves room for interpretation (and thus keeps you out of trouble). The storytelling operates via images, skilled montage, and juxtapositions. Like in the book, in Munk’s movie the action unfolds through Liese’s memories. We don’t know how reliable they are, but we slowly learn about the relationship between the two women as Munk systematically juxtaposes the story Liese tells herself with the reality of the camp. In the story that Liese tells Walter, she’s a benevolent pawn who, caught in the war machine, tried to escape morally unscathed by helping her fellow man as much as she possibly can. That image is incompatible with the real Liese, who as we slowly learn, is unscrupulous and particularly cruel.

Although Liese was the one in power, strangely it was Marta—with her stubborn contempt and ideals, her hardiness and resistance, and her devoted fiancé—who seemed to Liese more powerful. It was Marta, not Liese, who was certain of herself, and who was loved. Not even the brutality of the concentration camp could change that: Liese is lonely and unloved. Perhaps uneasy about her own choices, Liese needs Marta to be either on her side or to be destroyed. Marta’s resistance unsettles and unravels Liese; there is an unyielding power of righteousness in Marta’s pride, regardless of how powerless she truly is. Writing in 1964 in the Film Quarterly about the movie, James Price noted the psychological complexity of Munk’s masterpiece:

Even as far as his central character, Lisa, is concerned, her “guilt” or “innocence” are less important to [Munk] (and to her) than that she should determine the true nature of her actions. Not surprisingly, therefore, The Passenger is a film both of unequivocal directness in its statement of the facts and of a haunting ambiguity in its interpretation of those facts. Metaphorically, the hand is seen to rise and strike, but the reasons for the blow remain obscure (42).

Like the book, the movie is a subtle study of power, of the imperceptible markers that make power both personal and intimate. Throughout, we get constant flashbacks as the action moves between the gruelling scenes of Auschwitz and the joyful, careless scenes aboard the ocean liner. At the end, the two stories collide in a brief final encounter: but whether or not the mystery woman is Marta no longer matters. She still holds sway over Liese: the encounter unnerves her; but this time, Liese is powerless to retaliate, and she is left with the weight of her memory, forever unsettled.

Weinberg’s operatic adaptation of the novel lacks the intimacy of cinema, but such are the limits of the form: opera thrives on grand narratives and larger-than-life characters. In Weinberg’s opera, the relationship between Liese and Marta is more melodramatic and less complex than in the novel. Walter’s character is also not as multifaceted as in the book. His wife’s confession troubles him only insofar as it affects his career and their public image. He is not troubled by the ethical implications of her past (his brusque reaction seems to suggest that such confessions were commonplace in postwar Germany). Written in Soviet Russia, the libretto had to navigate difficult political terrain, and there are moments of clumsy propaganda. The only prisoner who resists degradation is Katya, a Russian woman who sings Russian folk songs and waits for the Soviet army to liberate her. Apparently, this wasn’t enough, as The Passenger’s first Russian production never came to fruition, but for modern audiences, Katya’s upbeat attitude does register as spurious.

Tablet Magazine’s Allan M. Jallon (2014) noted the strange absence of Jews in what is being billed as the “Holocaust Opera.” It is hard to argue with this point, as there is only one identifiable Jewish prisoner in the entire opera (and she’s meek and quite fatalistic), but it is also important to remember that the opera was written at the height of the anti-Semitic rhetoric and purges sweeping Eastern Europe at that time, orchestrated by the Soviets in response to the emerging conflict in the Middle East. Culminating in the 1967 Six-Day Arab–Israeli War, which delineated the Cold War’s political spheres of influence (with the USA supporting Israel, and the Soviet Union supporting the Arab States), the tensions in the Middle East indirectly influenced the situation of Jews in Eastern Europe. In his biography of Weinberg, Mieczysław Weinberg: In Search of Freedom, David Fanning suggests that in addition to the situation that fanned anti-Semitic sentiments at that time, Soviet authorities “always had problems with commemorations of the Holocaust, which they tended to regard as one-sided, in view of the colossal scale of Russian losses during the War” (qtd. in Woolfe). David Pountney also points out that “The Soviets wanted nothing to do with pity for the Jews: anything that did not actively further the communist agenda was officially condemned as ‘abstract humanism.’” The political situation in Soviet Russia necessarily affected Weinberg’s artistic choices; it does explain the virtual absence of Jews in the opera, and it most likely also helps explain why its first performance was cancelled.

Although the opera’s dramatic structure lacks the moral complexity and subtlety of the novel and Munk’s movie, the music makes up for all the shortcomings of the libretto. In his biography of Weinberg, Fanning called it “hard-edged and uncompromising” (qtd. in Ivry). The New York Times called the opera “harrowing and powerful.” Anthony Tomassini wrote:

Weinberg’s music daringly shifts from depicting the life of the well-heeled Germans aboard the ship to the horrors of the death camp. Now and then, in poignant scenes that eerily parallel the pleasantries of the ocean liner journey, the desperate inmates try to salvage a moment of cheer, as in one sisterly episode in which a group of prisoners tries to celebrate Marta’s birthday.

Polish Rzeczpospolita “praised the October Warsaw staging, noting the ‘startling impression’ it made through music that has ‘no heroism in it, but rather profound tragedy. Even in his melodic waltzes, [Weinberg] becomes a harbinger of doom, which indeed had engulfed his entire family” (Ivry). The New Yorker’s Alex Ross wrote:

The expected sombre passages in the opera are superbly done: bass chants of lamentation, plaintive songs for female prisoners of various nationalities, hammering ostinatos evocative of the industry of death. But it’s the addition of kitsch that makes the work supremely chilling: the anemic jazz that plays on board the ship; the lopsidedly bouncing music, in 5/8 time, over which Lisa explains to her husband that she was merely following orders; and, most of all, the commandant’s rancid waltz, which alternately sputters out over loudspeakers and thunders from the full orchestra.

The waltz has a double meaning. At the climactic moment of the Auschwitz storyline, the camp commander orders Tadeusz, Marta’s fiancé, to play his favourite waltz, but instead Tadeusz plays Bach’s Chaconne in D Minor. David Pountney noted that playing Bach is a gesture of “throwing an apogee of German culture in the face of its Nazi betrayers.” The waltz that Tadeusz didn’t play resurfaces at the party on board the ocean liner. The unknown passenger approaches the orchestra conductor and asks him to play something: it is the waltz. Liese recognises the music, and it unhinges her because it is proof that the passenger is Marta. The two women come closer but Liese backs away, further and further, into a corner: she is trapped literally and metaphorically, by the space, her memories, and her conscience. The inclusion of Bach at the climactic moment of the opera rather than his own music is a startling choice. Was Weinberg identifying with Tadeusz, or was there something else behind that choice?

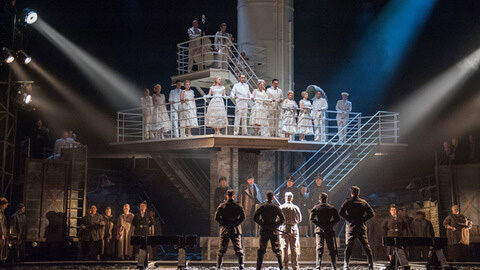

Johan Engels’ two-tiered set—with the upper level the deck of the ocean liner, and the lower level the Auschwitz barracks—and Fabrice Kebour’s superb chiaroscuro lighting enhances the contrast between the two worlds. The set and staging is somewhat hyper-realistic, veering into the surreal, but perhaps not surreal enough. Since World War II, artists and intellectuals have wondered how to aestheticize Auschwitz, and to what end. Many scholars and writers agree with Adorno and “view the Holocaust as virtually unrepresentable in language” (qtd. in White 43). Some, such as Claude Lanzmann, suggest that trying to represent, or even to understand, the Holocaust is in itself an act of “obscenity” (204). Many artists eschew any realistic representation of Auschwitz in favour of documentary or symbolist, abstract imagery. The setting and Marie-Jeanne Lecca’s costumes for The Passenger try to feel authentic, but what is an ‘authentic’ representation of Auschwitz on stage? The soft dress-shoes that the prisoners and guards wear in the opera are not authentic (prisoners wore wooden clogs and guards wore black leather boots). Watching that hyperreal reality, one becomes fixated on details. If this is Liese’s memory, shouldn’t the setting be as distorted as her own self-perception? James Paulk suggests that the problem is that the “libretto is neither rational nor abstract and not substantial enough to carry all this weight” (7).

Considering its history, The Passenger and its staging is a massive achievement. After the Lincoln Center performance, I ended up at a table with 90-year-old Zofia Posmysz, who was flown in from Warsaw for the occasion. She was frail but resolute, with piercing, thoughtful eyes. Julie Taymor sat between us and asked about the ending of the opera. In the last, epilogue scene, it’s morning, a new beginning; Marta sits on a riverbank. We can’t decide whether she survived or whether this is merely a fantasy of the afterlife. Tadeusz and all of her friends are with her in a scene reminiscent of the last tableaux of Les Misérables. She sings:

If one day your voices should. . . . if they should fall silent . . .

If they should fall silent, then we are all extinguished.

I hear you: “Do not forgive them, never ever.”

Katya, Katuscha, and you, Vlasta . . .

Hannah, Ivette, and you, my Tadeusz.

I swear, I swear I will never, I will never forget you.

Ms Posmysz doesn’t like this ending. She doesn’t like Marta being vengeful and unforgiving. She thinks it’s Christian to be able to forgive. Looking into her eyes, I am thinking of the limits of forgiveness, the limits of memory, and the power of remembering and forgetting. I try to find some cathartic conclusion to the opera, and I can’t. Perhaps that’s the point. There is no catharsis here, not for Liese, not for Marta, and not for us.

Works Cited

Fay, Laurel. Shostakovich: A Life. New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Groover, D. L. “The Passenger: A Forgotten Opera Exquisitely Crafted and Delivered with Power.” Houston Press Blogs. Houston Press, 22 Jan. 2014. Web. 10 Feb. 2015. <>.

“A Holocaust Tale Unfolds on Two Levels.” National Public Radio. Natl. Public Radio, 1 Feb. 2014. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Ivry, Benjamin. “How Mieczysław Weinberg’s Music Survived Dictators: Russian Composer’s Work Outlasted The Soviet Union.” Forward.com. The Jewish Daily Forward, 17 Nov. 2010. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Jallon, Allan M. “Lincoln Center Presents an Opera Without Jews, Set in Auschwitz.” Tabletmag.com. Tablet, 2 July 2014. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Lanzmann, Claude. “The Obscenity of Understanding: An Evening with Claude Lanzmannn.” Trauma, Explorations in Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1995. 200–20. Print.

“Mission Statement.” Adam Mickiewicz Institute. 5 Feb. 2015. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Paulk, James L. “The Passenger by Mieczyslaw Vainberg: Houston Grand Opera Gives the US Premiere.” American Record Guide 77.3 (May–June 2014): 7. Print.

Pountney, David. “The Passenger’s Journey from Auschwitz to the Opera.” Guardian.com. The Guardian, 8 Sept. 2011. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Ross, Alex. “Weinberg’s The Passenger: ‘Testament.’” The New Yorker. 5 Sept. 2011. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Price, James. “The Passenger (Pasażerka) by Andrzej Munk.” Film Quarterly. Vol. 18, No. 1 (Autumn, 1964), pp. 42-46. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Tommasini, Anthony. “What Lies Beneath: A Haunting Nazi Past: ‘The Passenger’ at the Park Avenue Armory.” NYTimes.com. New York Times, 11 July 2014. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

White, Heyden. “Historical Emplotment and the Problem of Truth.” Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the “Final Solution,” ed. Saul Friedlander. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992. 37–53. Print.

Woolfe, Zachary. “Sailing with a Ghost from Auschwitz: New York Premiere for a Long-Suppressed Opera.” NYTimes.com. New York Times, 4 July 2014. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

This article was first published in Cosmopolitan Review. Reposted with permission of the author. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Magda Romanska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.