Running Aug 24-29 at the 2021 Edinburgh Fringe, Every dollar is a soldier/With money you’re a dragon is an immersive digital performance about immigration, money, and colonialism from the contrasted perspectives of Britain’s early Chinese immigrants and William Waldorf Astor, Victorian millionaire and founder of Two Temple Place at the heart of London. Co-produced by Chinese Art Now (CAN) and the Two Temple Place gallery, Every dollar is a soldier describes itself as a “virtual promenade performance” that takes place in the after-hours of a digital gallery. Combining 3D technology and video games, the experimental work pushes the boundary of the theatrical experience and presents a mutual rediscovery between China and Britain of their historical and contemporary relations.

Upon entering the web gallery, audiences choose their avatars from a list of antique statues found in Two Temple Place or Chinese museum collections. I, a child Buddha, formed this night’s audience with a group of stone lion, Tang court lady, and D’Artagnan. Following the guidance of a glowing orb, I explored the gallery’s objects, installations and performances in the next 45 minutes with other audiences like in a multiplayer video game. It felt surprisingly satisfying to be able to interact with one another and the performance through simple gestures such as heart emoji, bowing, jumping, and running when my real body is confined at my desk in a city where public events are still restricted under COVID-19.

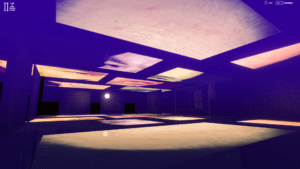

The gallery’s design is an intriguing clash of Chinese and European elements, historicity and fantasy, reality and virtuality. Although set in the magnificent neo-Gothic mansions of Two Temple Place, the 3D gallery displays a bizarre collection of the Chinese objects and artworks in abstract spaces that symbolically represent a Chinese harbor, the boat Chinese immigrants traveled to London, and Limehouse Chinatown. The gallery’s jarring aesthetics responds to the performance’s dramaturgy of juxtaposition and contradiction. At the start of the tour, writer/actor Daniel York Loh’s head looms above in a God-like fashion and embodies William Waldorf Astor, who tells us the story of the place and his family history. It turns out William Waldorf Astor was an immigrant who fled from his family’s base in Manhattan for London to hide from the hatred the Americans felt for his family. In 1895, he built Two Temple Place as his stone-built sanctuary from his enemies and estranged family. William Waldorf Astor is contrasted by a Chinese seaman, who jumped the boat in London around the same time Astor arrived. Through dance and classical Chinese music, the Chinese seaman recounts his life in China during the Opium War and involuntary travel to Britain due to human trafficking.

Daniel York Loh in a gallery room. PC: Ian Gallagher.

The seaman’s story reveals the other side to the Astors’ transnational business success, whose irony is implicated in the work’s title. “Every dollar is a soldier” is the Astors’ entrepreneurial proverb, while “with money you’re a dragon” is the Chinese idiom the seaman uses to mock his own impoverishment. In the performance, York Loh simultaneously traces the Astors’ family history and the history of the Chinese people, starting from the legendary Emperors Yan and Huang dated 5,000 years ago. York Loh observes that the making of the Chinese people is a process of contested unification, in which tensions between individuality and collectivity, diversity and unity are always at play. This internal struggle with unification, in turn, mirrors the European dichotomic imagination of the Chinese as a homogenous faceless group of “Other” that is either romanticized or demonized. These questions about the evergoing cultural encounter between China and the west enrich the performance with a contemporary, globalized perspective.

The display of a paper gown by Chloe Wing. PC: Ian Gallagher.

While listening to York Loh’s voice-over, I wandered around the Chinatown section of the gallery — a space of red lights mixing both oriental stereotypes and installations by contemporary Chinese artists. I consider the experience an inversion of the Chinese collection in the British Museum. Where the Chinese objects are arranged and represented under the frame of the British Museum’s neoclassical architecture and positive imperial narrative, the Chinese materials in the digital gallery return the gaze and take ownership of their narratives. Only then, an intercultural dialogue could happen.

Dialogue is made by two. To produce the performance, Two Temple Place also opens itself up to new visitors and narratives. In the post-show Q&A hosted by Horizon, designer Christine Ting–Huan 挺欢 Urquhart explained the design of the digital gallery was inspired by the scars on the walls of Two Temple Place. In the gallery’s 3D model, she hopes to crack open these scars to let light in, hence the open ceiling and transparent walls. Curiously, York Loh’s performance suggests that the reason for the construction of Two Temple Place was exactly William Waldorf Astor’s fear for the outside world and the people. The performance reveals to us that Astor is in fact connected with the Chinese seaman — not just by the inequal imperial system, but also in their deepest struggles with migration, belonging, and building something to hold onto, which are common to all mankind. The symbolic significance of the collaboration between Chinese Art Now and Two Temple Place converges in theatre and in real life.

The digital gallery is still open to the public at https://chineseartsnow.org.uk/two-temple-place-exhibition-no-film/.

Scrolls and the orb. PC: Ian Gallagher.

Every dollar is a soldier/With money you’re a dragon

Writer/Actor: Daniel York Loh

Director/Composer: An-Ting Chang

Designer: Christine 挺欢 Urquhart

Creative Technologist: Ian Gallagher

Director of Photography: Zhou Ning, Adam Ryzman

Choreographer/Dancer: Si Rawlinson

Musicians: Wang Xiao (erhu), Cheng Yu (pipa)

Performer/Artist: Chloe Wing

Interface Designer: Rich Brown @rvlvagency

Film Studio Partner: Broadley Studio

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yizhou Zhang.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.