The LookOUT Arts Festival, presented by Ibsen International, takes place in Beijing from July 6-15, 2018. LookOUT is a kaleidoscopic ten-day program of performance, visual art, film, talks, and creative writing. It is the first of its kind in China, responding to one of the great themes of our time: gender.

Under the theme of “Beyond,” the festival’s pilot edition is composed of four main sections: the performance program, “ReachOUT,” features a range of renowned and emerging artists addressing gender issues in their work; the “SpeakOUT” Lecture Series turns the spotlight on urgent conversations we need to have on gender, led by artists, thinkers, and academics from China and abroad; “China-ComingOUT” builds on the fruit of previous creative writing workshops, in partnership with Queer University and Shanghai Pride. This session presents a collection of personal reflections on gender in public script readings and continues to empower the Chinese LGBTQ community by celebrating their talents and daring in storytelling; “TryOUT”–an audacious creative platform, in collaboration with the Faculty for Dramaturgy and Applied Theatre Studies of the Central Academy of Drama–supports young people to express and challenge their opinions on gender, state and society through art practice and critical thinking.

Ahead of the festival’s launch, I spoke with Festival Director Fabrizio Massini about the importance of creating an open space to share knowledge that gives a clearer view on gender, art, and theatre’s potent power to remind us to keep a watchful eye on what surrounds us. He also shares insights on what goes into bringing thought-provoking and celebratory arts on gender to Beijing, China’s political capital, and the heart of its censorship machine.

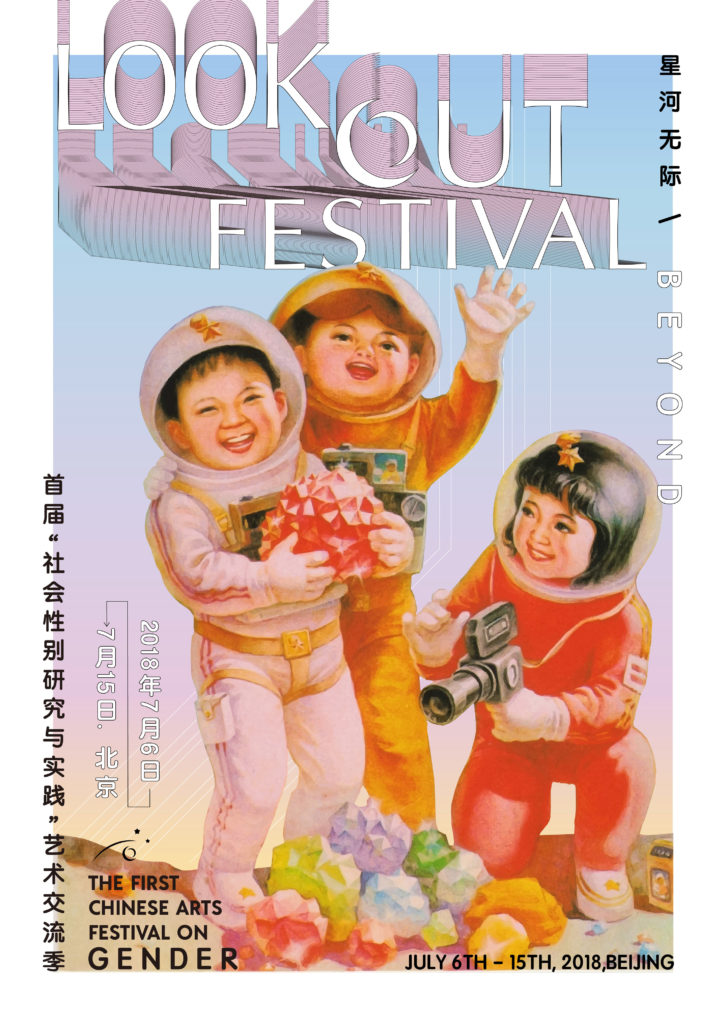

Look Out Festival poster

Shiya Lu [SL]: Congratulations on launching this new festival! First of all, what inspired you to create an arts festival on gender in China?

Fabrizio Massini [FM]: It’s something I’ve been thinking about for years. Having lived in China for ten years, I feel that gender-related issues are not tackled in a nuanced enough way. Gender is a very crucial topic for contemporary Chinese society. The civil society is progressing quickly, way ahead of the establishment, and gender diversity is developing fast as a counterculture. I think the arts can go a long way opening it up for the general public.

SL: So do you see this project as China-specific? Or does it relate to the global scenario too?

FM: The struggle for gender equality is a global arena where two approaches clash: one is trying to drive us back into the dark age, the other embraces diversity, inclusivity, and change. Today, China is a global key player on so many levels; it is shaping the world through economic and political influence. Which way China decides to go may well determine the unfolding of this debate.

SL: And art will save the world?

FM: I don’t know about that! We try to promote artistic and academic practice focusing on gender, inviting the general audience to reflect and share their opinions. This way we hope to inform opinion leaders and participate to create a consensus on these themes.

SL: The theme of the pilot edition is “Beyond,” so what core message is it trying to convey?

FM: The theme came from a conversation with Lai Huihui and Martin Yang from the LookOUT team. The Chinese version of the theme, xīnghé wújì, literally translates as “Galaxy Without Borders,” and captures the spirit of our first edition. It also reflects on our visual identity incorporating retro-futuristic aesthetics with 1980s propaganda posters promoting China’s early space missions. On the poster you see a group of cheerful astronaut-kids searching for shiny gems. I guess the message is: “we can be excited, curious and open towards the unknown, rather than intimated or scared.”

SL: Norway is recognized as one of the most LGBTQ-Friendly countries in the world. You mentioned the King of Norway’s inspirational speech from 2016 in which he declares that Norwegians include “Girls Who Love Girls, Boys Who Love Boys.” As a Norwegian cultural company dedicated to creating long-term relations with China within the fields of art, culture, and research, is it correct to say that LookOUT is advocating the Norwegian values of tolerance and inclusivity?

FM: Absolutely. Ibsen International embraces the values of equality and inclusivity which are central values in Norwegian society. Since the company was founded in 2010 by Ms. Inger Buresund, it’s been our mission to initiate a dialogue based on these values, amongst other core values.

Li Ning, Untitled 3, video still (Photo Credits: Li Ning)

SL: Someone could read this as a soft-power strategy, given your affiliation with Norwegian state institutions.

FM: This is a possible reading, to which my answer would be: “we work with human beings, not with buzzwords.” Our work is supported by the Norwegian Embassy and Consulates in China, to whom we are incredibly grateful. But we’re an independent cultural organization curating projects focused on contemporary topics and universal values. Individuals have joined because they believe in them, regardless of the passport they hold. I think this is exactly why Ibsen International has gathered such positive responses and initiated many collaborations throughout the years.

SL: What trends have been noticeable in China’s LGBTQ rights movement and gender justice?

FM: I have to admit that my understanding is limited as I mainly worked in major Chinese cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. In these areas, you can see more openness, meaning diversity in gender identities are not a “big deal” anymore, especially amongst the post-80s generation and below. You see same-sex couples being out with friends and colleagues and there’s less stigma around them.

SL: However, wouldn’t you agree that the situation worsened since the change in leadership?

FM: In the past years we witnessed a dramatic increase in the censorship’s grip at all levels: citizen’s online activity, public events, education, everything is closely monitored. Gender is just one of the sensitive topics that now shows up more on the censorship’s radar. But the picture is more complex than that. Several celebrities self-style themselves as “LGBTQ icons” even though they haven’t yet publicly come out. It is a sort of “selective encoding” strategy, hiding layers of meaning between the lines, that enables certain communities to communicate without publicly defying the heteronormative views and the authority’s guidance.

SL: I remember a conversation we had in April after China’s social media giant Weibo reversed the ban on “homosexual” content after an outcry, you said: “we are not going to stop.” Can you briefly comment on this?

FM: There’re a few interesting aspects of that episode, which is a milestone in China’s LGBTQ movement. The ban was announced by Weibo as part of a “clean-up” grouping homosexuality with pornography and pedophilia; a real outrage. Firstly, the huge response included mainly “allies,” people who aren’t LGBTQ themselves but publicly condemned it as backward and unacceptable. Within hours, #IAmGay was trending and by the time it was censored, it had reached 300 million views. Secondly, the People’s Daily (the historical mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party) reminded that homosexuality is a legitimate sexual orientation and asked for tolerance, going directly against Weibo.

SL: What do you make of such a complex scenario?

FM: There are many speculations about Weibo’s u-turn: was the public reaction bigger than they expected? Or did they back off after seeing Sina’s stock price plummeting? Was the whole thing orchestrated to test the public opinion? We’ll understand better this incident in a few years…

SL: As someone who travels frequently in and out of China, between two sides of the Great Firewall of censorship, what are your biggest fears and challenges when planning this festival?

FM: The biggest fear is that the whole thing will be shut down! This is a very real threat when you work on sensitive topics. Apart from that, the main crucial challenge is to introduce this topic in an attractive, inclusive, audience-friendly way. We don’t want to preach to the converted. We are trying to connect with people who have no clue what we are talking about and encourage them to share their own ideas.

SL: What are your main focuses when selecting works for the festival?

FM: It’s a delicate balance between artistic standards and a dialogue with our audience, within the community and beyond. I aim to have a cohesive program with artistic integrity speaking to a larger audience, to open up conversations on gender from different perspectives: LGBTQ rights, gender equality, feminism, domestic violence, etc. We want to make this statement clear: you should take a stand and participate in gender policy-making because, otherwise, it will shape your life without you having a voice in what’s being decided.

SL: How did you cope with balancing “dare to ask questions” and “keep the festival and artists safe?”

FM: And here comes the million dollar question! I’ve been struggling with it for ten years. For me, doing performing arts in China is so important because it represents a kind of bubble; the safest place to have dangerous conversations in, if you will. Of course, you need to be aware of the limits and find creative ways to go around them. Like walking through a minefield: you need to make deviations, it may take longer than going straight ahead. It’s important to keep your eye on the goal and arrive there without blowing yourself up! This time I’m working with supportive venues and an amazing team with extensive experience dealing with censorship mechanism. I feel very lucky to be part of this team.

Wang Xingchi, A Self That Differs (Photo Credits: Wang Xingchi)

SL: Browsing through the program, I must say that I am most excited and moved by the TryOUT Platform. Through artwork and performance rich and diverse in format and content, the students show their awe-inspiring talent, and manifest their courage to push boundaries and think profoundly on complex issues such as sexuality, patriarchy, gender equality, and child sex offenses. What do you think of these liberal, social media–savvy generation of artists and theatre-makers living in a country that has a long way to go in the field of LGBTQ rights and gender justice?

FM: I’m so impressed. It is refreshing to see this younger generation having such open mind and a keen interest in gender topics. It is also the credit to their teachers, Dr. Li Yinan and Kai Tuchmann, who did an incredible job opening windows for the students. What Ibsen International is trying to do is supporting the students to realize their projects, from conception to production, to bridge the young creatives and the spectators.

SL: You were a student at the Central Academy of Drama almost a decade ago, and now you’ve returned to work with the teachers and students as a festival curator, what are the changes in attitude and working methods you have witnessed?

FM: The academy is a big institution with many forces who have different understandings of theatre and of the school’s role. I think some new voices within the academy have renewed many aspects, by redesigning the course structure and opening up exchanges with foreign teachers and academics. Before it was more of a tokenism, showing off their Foreign Experts for the sake of it. Now the collaboration is deeper and the exchange goes both ways.

Look Out Festival Director, Fabrizio Massini

SL: What are the things you’re most excited about at this new festival?

FM: Everything, really. I look forward to seeing who will show up, and what they will take away from the festival. The conversations that will happen after the shows and lectures, because this is what makes the Chinese scene so exciting. People not only show up to consume a show and then leave; audience and creatives are willing to linger and negotiate the meaning of the event. It nurtures new perspective from both sides.

SL: In terms of LGBT rights and gender awareness in China, what do you envision the situation be like, five, ten years from now?

FM: My hope is that there will be openness and acceptance towards diversity because it enriches a society. We can share the same space without censoring certain voices and make use of these differences to have a better life. Maybe it is a bit utopian, but I truly believe in it.

SL: Finally, what’s the next after LookOUT Festival?

FM: We will host more “SpeakOUT” lectures and another session of “China-ComingOUT,” the creative writing workshop co-curated with Hege Randi Tørressen, at the end of this year. I look forward to “LookOUT 2019,” maybe partnering up with another school for the “TryOUT Platform,” maybe a fine arts academy. I hope this festival, as an artistic force, can be a stable point of reference in the years to come.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Shiya Lu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.