Let’s be clear from the outset. This performance has absolutely nothing to do with Surrealism, nor is it too long. Rituals go on endlessly and repeat themselves non-stop. Clearly this particular theatre-ritual deals with one of the most disturbing and shameful situations we have ever experienced on our collective territory: the murder of women from First Nations, Métis Nation, Inuit groups. In spite of the hearings, investigations, and apparent concerns for these lives, no guilty party has ever been identified or punished. These murders are treated as unsolvable mysteries, and the women themselves are relegated to “accidental” beings who perhaps never even existed! But they do exist, and still exist, as Marie Clements shows us in this powerful encounter between her theatrical conception of their lives, and director Muriel Miguel’s choreography. Along with a list of extremely talented collaborators, the voices of the disappeared who still inhabit the natural world are still speaking to us through these artists.

Andy Moro’s striking set greets us as the sky lights up revealing tall, thin curtains covering immense structures suggesting huge redwoods of the BC coast in the shadows. A logger sneaks quietly through this forest with his chain saw and begins cutting these majestic structures as they scream in pain.

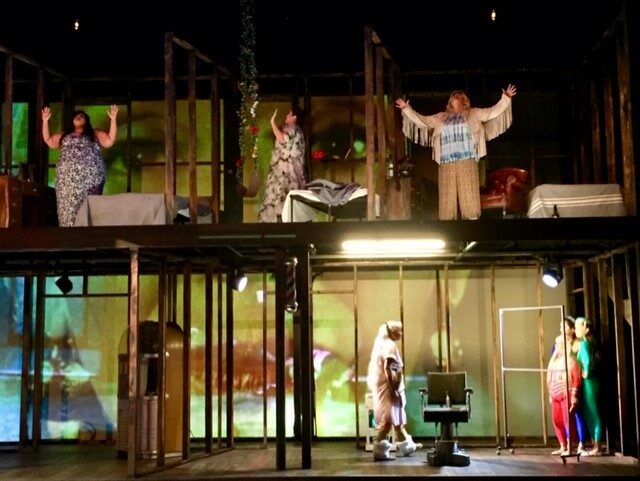

As the forest collapses, a half-naked woman with long grey hair, her legs covered with red growths – blood? flowers?- crawls out from under a pile of leaves lying in a circular space on the ground. Bewildered and confused, this spirit creature, a transformed aunt Shadie, moves through the maimed forest world calling up her daughters who appear on the set. They rapidly transformed into a structure that resembles an upper horizontal space suggesting a rooming house, where women occupy a row of tiny bedrooms. All is enveloped in a sea of changing lights and video designs.

On the ground floor, a public space morphs into a bar, or a dance hall, or a street area or even a barbershop. One young woman sits at a bar table and seems to be writing, or thinking or observing all that is happening. This is Rebecca (PJ Prudent)! She tells us she is still searching for her mother who suddenly disappeared 20 years ago and has never come home.

The Unnatural and Accidental Women. Set by Andy Moro. Photo credit Barbara Gray.

Then again, Moro’s powerful colorful video-effects highlight a constantly-transforming space that appears to be alive behind and above the structure in the foreground. It incorporates the coastline, the interior of the city and even a run-down area where the Vancouver rooming house is planted. The site is split into various moving surfaces that reveal a living place trying to tell us something excruciatingly painful.

This is a beautiful incarnation of a First Nations space of storytelling; it progresses neither forward, nor backward nor sideways nor anywhere in linear time. The background is constantly jolted by melting water, by burning growth, by angry spitting fire or by the sudden appearance of dark rolling clouds that rise threateningly over this whole world. These suggest projections of the pain that gripped the female figure who emerged from the ground in the first minutes of performance and continues to observe the whole event taking place before us.

Then the lives of the women living in these miserable conditions, who automatically respond to the male mantra “can I buy you a drink?”, begin to define themselves. Troubled and forced to leave home, they enter a spiral of alcoholic relief from the horrors of their life against which they have no defense. Such as the local barber, a male archetype, preys on their situation. Pierre Brauls becomes a terrifying creature, giving vent to his sadistic attraction to young native women and showing us a possible scenario of drinking and killing that is at the origin of all the deaths.

There is a rush of bitter street talk, a world of pleading chatter on the phone in search of a relative, tense chatter about marriage and dating, and children. There is angry vulgarity, trembling fear and helplessness, violence, and cruelty. It all suggests a magnificent poetry on the part of the author Marie Clements and director Muriel Miguel. Miguel coordinates the group of women, caught in this pornographic nightmare that splashes their lives across the burning sky, announcing their fate of how they died of a high level of alcohol in their blood in news broadcast style. The coroners inevitably decided that these deaths were all “unnatural and accidental.” No one was to blame. Nothing left to do, and the European-based system of justice is incapable of ‘seeing’ what has really happened. This event at the NAC shows us quite the contrary.

As the first part of the evening unfolds, the misery and the sordid state of these dying women seep into our minds. Their grieving is echoed by a hardy beating of the drums, a loud high pitched chanting as each of the women reacts defiantly, making a fist, twisting arms in a fighting stance, expressing some strong emotion as they call out to the spirits to come down to help them reclaim their lives. Participating in this event we become annoyed, then angry, wondering why this state of affairs has not been solved and why it has been allowed to fester. We want to get out into the foyer of the theatre, breathe fresh air and yell at someone.

This visual and verbal performance was never conceived as an imitation of reality, but rather as a transformative ritual event that has left its suffocating mark on the spectator. We need a bit of time to cool off before we go back into the theatre for more of it after the intermission. However, is cooling off the answer? Have we become so immersed in these horrific details that they engulf us and we are no longer free?

Act II:

The dead women have returned from the other world where they meet again in that sordid rooming house. It appears to be less sordid now because of brighter lighting and the determined presence of Rebecca who wants to solve the mystery of her mother. Rebecca is now plotting something daring, and they watch her manipulate the dangerous barber: setting him up for the kill, making sure he cannot escape. Rebecca greets these spirit women where they all submit to intimate confessions about their needs, their desire to have a man, to no longer be alone. They confess how their lives have been stolen from them. They are very curious about this handsome new younger male who appears friendly and beautiful, and they look him over as though he were a foreign animal.

The excitement mounts: there is playful collaboration which becomes a most satisfying act of vengeance that brings Rebecca back into contact with her mother. Aunt Shadie, incarnated by the inimitable Monique Mojica, prepares a celebratory tea party as soon as the sacrifice is over. As the wind echoes their feelings they lock arms, move in a circle that reorganizes itself in various corporeal relations. Through reclaiming their solidarity, chanting, and dancing they find their way back to the other world, no longer victims of an accident. They have found their own path back to the ancestors and will be received at home with great ceremony identifying their own personal origins such as the Salish girls, and so many women of other the west coast families. The spectators suddenly find themselves in a terrible vacuum.

The Unnatural and Accidental Women continues until September 21 in the Babs Asper Theatre. It begins at 7h30

Written by Marie Clements, directed by Muriel Miguel, set designed by Andy Moro, costumes by Sage Paul, lighting by Jeff Harrison, sound designed by Troy Slocum, choral director, and Composer Soni Moreno.

This is a co-production by the NAC Indigenous Theatre and the NAC English Theatre.

We gave already seen Marie Clements’ work in Ottawa at the National Arts Centre (Copper Thunderbird, directed by Peter Hinton, 2007) as well as The Edward Curtis Project (Co-produced in 2013 with the Great Canadian Theatre Company. Her play Burning Vision will open at the National Theatre School in Montreal this winter.

This article was originally published on http://capitalcriticscircle.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alvina Ruprecht.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.