Okay, COVID-19 really sucks. This play opened and closed on the same night, 4 November, as the second lockdown this year closed all entertainment venues in the country. Luckily, there had been 10 performances in the socially distanced Olivier auditorium of this national flagship venue so that a fair number of people had been able to witness Michael Balogun’s blistering solo performance in person. A sequel to Roy Williams and Clint Dyer’s Death of England, which had opened before the pandemic, this brilliant high-octane monologue tells the story of Delroy, who was first introduced as one of Michael’s mates from childhood in the first play.

Because the press night performance was filmed, Death of England: Delroy can now be streamed in advance of London’s theatres reopening next week. The story is simple: Delroy is a thirtysomething working-class black man whose girlfriend, Carly Fletcher (Michael’s sister), is about to have their first baby. On his way to the hospital, he’s in a hurry and is stopped by the police, and then reacts badly. He is under a lot of stress so that is not surprising. But his outbursts of anger only make the cops more vicious, and when he knocks one of them over they arrest him. Take him to the station. As Delroy gives his account, he sketches in various scenes from his life which offer a perspective on this case of police harassment.

Central is the moment when Delroy describes his mother’s reaction to his arrest. She thinks that it’s his fault for becoming too aggressive. Her philosophy, which hails from the Windrush generation, is not to fight the cops, but to use kindness to wrong-foot them. Be polite and they will lay off you; be aggressive and they will beat you. Don’t give them that satisfaction. Use your head. She didn’t raise a fool, so don’t make a fool out of yourself. But her good sense does not prevail. When it comes to the court case, Delroy makes the same mistake that Michael made at his father’s funeral. He talks too much; he makes a speech to the magistrate. Big mistake. His mum tries to stop him, but to no avail. It’s a genuinely excruciating episode.

Delroy’s mother also has a negative attitude to his relationship with Carly. This young white woman might be okay, but can she really understand what it’s like to be black? She can be anti-racist, but can she really feel the reality of that — from the inside? And why can’t Delroy just settle for a nice black girl? This mirrors the doubts that both Carly and her mum, Maggie, have about Delroy. If, as a father, he can’t even get to the hospital in time, he’s not really fit to be a parent. Yet Delroy does have a good job as a bailiff, and makes enough money to buy a place to live and run a car, so when the black cop at the station calls him “boy,” you can see how angry that makes him.

Williams and Dyer write this complex monologue with all the scorching fire of emotional truth. The storytelling is fragmented and often indirect, with digressions, opinion speeches and some powerful dialogues as Delroy confronts Michael and Carly. Like the first Death of England monologue, this one is as gripping as a chokehold, with the words squeezing out, both sweat-soaked and adrenaline-powered. Deep feeling makes hearing the writing’s bruised and bruising eloquence an overwhelming experience. Delroy’s sensations of pride and shame come across strongly as he confronts his own masculinity, the burning injustice visited on himself, and his friendship with Michael.

A key theme is national identity. Although Delroy has voted twice for Boris, and for Brexit in the EU Referendum, he has no illusions about being British. Sure, he was born here, but he notes that white people have lived for generations on this septic isle. And that makes it difficult to compare the experiences. As he discusses the British “island mentality” and “English amnesia,” it becomes clear that his support for Brexit is actually an act of subversion. If leaving the EU is an example of national self-harm, then he wants to harm the nation that treats him so badly. The 80-minute one-man show ends with a cry from the heart: as a father, he has to wake up and think of his baby’s future — the struggle continues.

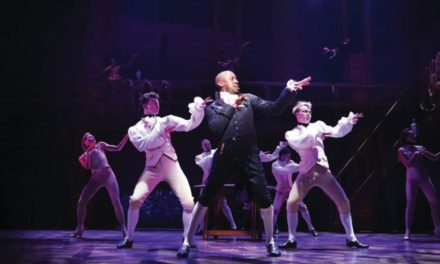

Dyer directs this explosive show and Michael Balogun delivers a performance that has both head and heart. Starting off as a Guinness-slurping, loud-belching drinker, his Delroy goes on a journey of self-discovery in which he faces himself in all his pride and with full knowledge of his defects. At times this is both revealing and moving, as if he’s taken a torch and shone its beam directly on the character’s soul. Whether boiling with anger or sobbing with shame, he is utterly convincing. For ironic relief, Dyer and designers Sadeysa Greenaway-Bailey and Ultz have included some visual illustrations, the bust of Nefertiti for Delroy’s mum, a heroic statue for Carly, and a golliwog to represent the black cop.

Matthew Amos directs the filming with skill, making this streaming — with its introduction by the authors and its passing shots of the socially distanced and masked audience — a fitting record of theatre in a time of pandemic. At the same time, this show also raises the hope that Williams and Dyer will write another play to complete the trilogy, maybe telling Carly’s story. In that case, all three plays could make a devastating day-long show, lifting a mirror to us the audience, in whose depths we could see reflected both the good news and the bad about who we really are as a nation. In the meantime, Death of England: Delroy is a sublime example of contemporary new writing and an instant classic.

- Death of England: Delroy returns live to the National Theatre in Spring 2021.

This article was originally posted on sierz.co.uk on November 27, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.