In her debut film, Małgorzata Dziewulska takes on a challenging task: revising Grotowski’s discourse via the main advocate of the discourse, Ludwik Flaszen.

Grotowski←Flaszen, dir. Małgorzata Dziewulska. National Audiovisual Institute, 2010.

There’s a scene in Małgorzata Dziewulska’s documentary Grotowski←Flaszen in which Flaszen, wearing a ribbon hat, a jacket, and creased trousers, strolls along the bridges that stretch across the canals of Wrocław, like Aschenbach in Visconti’s Death In Venice. He describes a humid, foggy Wrocław, not unlike Thomas Mann’s Venice.

Death, passing, and forgetting–inextricably linked with a lack of understanding–all appear in the film’s somewhat importunate opening scene, where the clockwork in a church spire, like the machinery in a film projector, measures out the time during a historic recording of The Constant Prince, presented here in its silent version, with no soundtrack. Dziewulska composes her film out of afterimages, shreds of discourse, tropes, legends, conjectures, and speculation cut short in the most electrifying, unorthodox moments. Hardly anyone talks about Grotowski in such a manner, and hardly anyone can. The reception of his work has thus far consisted of reconstructions of his thoughts and synopses of his plays. Assuming a thoroughly opposite approach, Dziewulska multiplies inconsistencies, tracks fissures, and explores the variety of ways in which we talk about Grotowski.

Grotowski is presented as a theatre director with close ties to the body, the concrete, and structure, but also as a devotee of the esoteric, an aspiring mage (“Who wouldn’t want to be a Mage?” Flaszen asks). His is the theatre that longs for contact with people and yet abhors crowds, a theatre reserved for a select audience (“an elite venture,” as Flaszen describes it). Esoterica, magic, elitism–these words have been deprecated and deconstructed in every possible manner in contemporary theatre. The question about the communicativeness of the Laboratory Theatre is presented in the documentary as a multi-layered issue, one that finds refinement, if only in the intellectual sense, as Dziewulska’s images lose themselves in their intrusiveness and stagedness (such as the aforementioned clock, and one scene where Flaszen is interviewed over a video conferencing setup); the question of communicativeness also applies to the most fundamental quality of the theatrical medium: its fleetingness, its incidental nature, the fatal disease inherent in the medium (which is why the theatre revels in the subject of death).

Grotowski has left us his archives, and what is left of his theatre are more or less apt descriptions of his plays and technically imperfect film recordings, as well as a handful of pictures. “We’re inundated with dead human voices, voices coming from speakers.” This diagnosis of the contemporary audiovisual world, expressed by Flaszen and intended as a contrasting image to the participatory, active, and live theatre of Grotowski, also describes the heritage of the Laboratory Theatre (precisely the paradox emphasized by Dziewulska). When Flaszen talks about the Great Dialog of International Theatre (his capitals) that went on between him and Grotowski at a train station bar, he is also talking about the dialog of dead voices. To us, these voices are dead; they are like the murmurs collected by spiritists in empty rooms and long-abandoned homes.

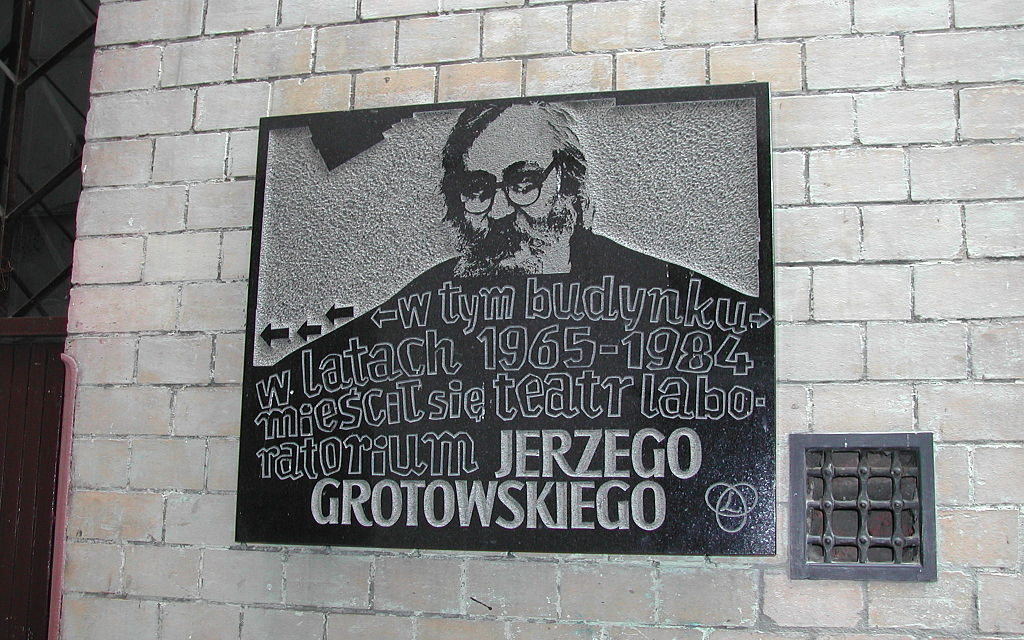

Grotowski continues to haunt us–quite literally, in the case of this film. His spirit protests the shooting of the documentary, interfering with the cameras, and attempting to drown out Flaszen’s story by possessing an electric drill (why not?) It’s an obvious reference to the theatrical legend about the curse of Grotowski that falls upon all who disobey him, and Dziewulska’s document would certainly not be approved of by Grotowski, at least the Grotowski that has been captured and imprisoned, like a genie, in the canonical discourse. The truth, as I see it in this film, is that the famed Acropolis Hall at Wrocław’s Market Square and the Grotowski Institute founded in this “hallowed” hall is nothing more than a religious souvenir stand. What’s worse is that these souvenirs are theoretical and intellectual.

In the final scene of the documentary, we see Flaszen as he watches The Constant Prince projected onto an enormous outdoor screen in Wrocław’s Market Square, a few dozen meters from the former location of the theatre. He doesn’t hide his indignation, and he’s probably not the only one. I find the view just as sad. But after a moment of sadness, there comes reason. This elite theatre, Dziewulska seems to be telling us, will either be interpreted through contemporary discourses, or (and I’m afraid this is the case) it will die, sighing to the ghost of Tadzio, in whom Aschenbach saw “the poets’ annunciation of the birth of the gods,” a view shared by the interpreters of Grotowski.

Grotowski←Flaszen

The National Audiovisual Institute has completed the production of the film Grotowski←Flaszen, a cinematic story about the 20th century reformist of the theatre, Jerzy Grotowski. The film features Ludwik Flaszen, the co-creator of the Laboratory Theatre. By describing their friendship and common interests, the film tells the personal story of an exceptional phenomenon, interspersing interviews with footage of theatre productions, television programs, documentary films, and rare photographs. By presenting episodes from the history of Wrocław, the film poses questions on the relationship between public events and the phenomenon of the Laboratory. The film was produced by the National Audiovisual Institute.

“The movie is an essay documentary,” says essayist and theatre director Małgorzata Dziewulska, for whom Grotowski←Flaszen is a debut film. “It contains a minimum of historical explanation and is more of a reflection on the power of Grotowski’s philosophy and what it means to us today. I wanted to touch upon a great mystery without judgment or generalization.”

Translated by Arthur Barys

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in April 2011 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Pawel Soszynski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.