I feel there’s a straight line from Mrożek to Dorota. She’d probably kill me if she heard me say that. Or maybe she wouldn’t be offended. But I hear it.

On the Lower East Side of Manhattan until the end of February, Dorota Maslowska’s first play receives its New York premiere. A Couple of Poor, Polish-Speaking Romanians runs at Abrons Arts Center, directed by Paul Bargetto and co-produced by his company, East River Commedia, with the Polish Cultural Institute in New York. The production utilizes Benjamin Paloff’s translation, commissioned by the PCI for a staged reading in 2005 at the PEN World Voices Festival at the City University of New York. Paloff had translated Maslowska’s first novel for Grove/Atlantic; his translation of the play will be in the anthology of recent Polish drama, Eat The Heart Of Your Enemy, published by Seagull Books later this year.

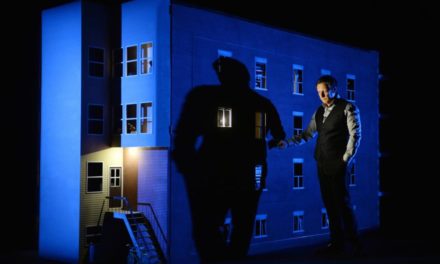

Paul Bargetto, archive of the Polish Cultural Institute in NYC

Alan Lockwood: What led you to Maslowska’s piece?

Paul Bargetto: I’ve done previous projects with the Polish Cultural Institute when Paweł Potoroczyn was the director. I did a series of one-act plays by Sławomir Mrożek. In 2003, we did Striptease and Out At Sea, at La MaMa*, a production that really got my career started when I got out of grad school. After that, I was just in love with Mrożek. He really spoke to my own sensibility, but also to the times. It was pretty fresh after 9/11 and there was a lot of discussion about what kind of security apparatus we were going to set up in this country. And the way terrorism was this inexplicable power that you didn’t really understand.

I continued on that line and picked up a couple of more Mrożek one-acts. We did Philosopher Fox and took it to the Malta International Festival in Poznań, and played it in English to a Polish audience. We brought that show back and ran it guerilla-theatre style in Central Park for almost eight weeks. We did it in front of the line that was queueing for Shakespeare in the Park, so they had to watch it. After that, the Polish Cultural Institute produced it and did that with another Mrożek one-act, Serenade. That was my long primer on Polish theatre by one author.

About two years ago I went to visit Agata Grenda [deputy director and theatre programmer at the PCI], and I said, “Hey, it’s been a while since we did anything, why don’t we make something?” She said “Sure, what do you want to make?” I said, “I want to do someone contemporary, I don’t know who’s the hot author right now.” She gave me three or four plays, and among them was A Couple Of Poor, Polish-Speaking Romanians. As soon as I read it, I knew this would be the next play that we’d do.

Was this the script that Oberon Books published in London, or was it Benjamin Paloff’s direct translation?

It was his direct translation. I have to say that Benjamin’s translation is ferocious. And I can’t imagine that she’s an easy writer to translate. Often translations are very hit or miss. This one’s extraordinary.

I’m intrigued to know, you said you saw her last play, right?

I saw No Matter How Hard We Tried for the second time in December, at TR Warszawa. The first time was while on the jury of the Divine Comedy Festival in Kraków in 2009, where it was the all-but-unanimous choice for the grand prize. It should be the next TR production to come to New York; it’d intrigue and confound audiences here.

How are you dealing with Masłowska’s prologue, which was altered in the original TR production, and with the dual hanging at the end?

We’re still sorting out the final details about how to attack this. A reason I like this so much is that it presents incredible staging challenges to the director and the ensemble, without any guidance. As a director, that kind of challenge makes me sit up. My window into this, one of the themes if you want to call it that, is that I see this play as being bigger than a particular Polish commentary. I see it as a reflection of our own mass popular consumerist culture, being reflected back to us in a very brutal, very funny way.

I’ve been thinking about how Eastern European countries were in ways hermetically sealed from the West—in general, very closed off. Suddenly you had this virgin market opened up overnight to this very sophisticated consumerist culture, with all of its very carefully wrought seduction. It came flooding into countries used to a brutal, simple propaganda. They didn’t know what hit them. It spun everyone’s head there.

I was struck by was how new all the marketing jargon sounds in the characters’ mouths. These are words we don’t even hear anymore because it’s a constant stream. It’s beyond our daily level of comprehension anymore. Here it is being reflected back to us, and it felt like these are things that have meaning, whereas everything else that they’d had, had lost meaning. But what is that meaning? It’s mostly meaningless, it’s marketing.

One of the windows that I’m going to be looking through in terms of design is television. We’re going to have it in the piece, and periodically we’ll be going back through that window. Another thing, keeping on that theme of television, is the fact that the main character is this popular television actor. I was fascinated by this; I didn’t realize that there’s this phenomenon in Poland of Catholic soap operas.

There’s a Masłowska quote that that’s where many Poles are getting their Catholicism these days, not from the priest but from the TV.

Exactly. We don’t really have anything like that here. I felt that for the audience to get that, they have to see it. We’re going to make our own episode of Father Ted, which will be intercut on the TV in different scenes. For example, when they go into the Tasty Grub, which is this horrible diner, they’re watching TV when they walk in and it [the episode] will be on. Then, of course, they don’t recognize him, which is very ironic.

That’s another theme that interests me, thinking about Polish history, that the church, though it’d been allowed, had been controlled and edited. When communism ended, the church was free to become a normalist tradition and have its say. It fascinated me that they then went on television: it was understood that if you’re not on television, you don’t really exist. Which is a very American tradition.

It includes a commentary on the church and its new place in power. To me, this piece feels a bit like one of these religious pageants. There’s something in the structure of the drama, I’m not exactly sure what it is, it’s not on the surface at all, it’s somewhere deep in the substructure. It feels like there’s an allegory at work there. The fact that the main character is playing a priest, in the popular imagination of Poland he’d be one of these perfect men, a paragon of religious virtue. Of course, throughout the play, he’s a total degenerate!

Three acts in turmoil…

And yet when I think of the woman Gina, she’s really from the bottom rung. A single mother, living at home in a dirty apartment in Warsaw. She goes to this party and meets this famous actor who goes off on this mad journey with her. Part of her motivation, I think, is to be saved. So they start playing that out, that “He’s going to save me.” It’s a twisted take, but I think it’s an interesting core of the play that makes it universal. Those are things that drew me more immediately than the obvious xenophobia that Masłowska is sticking her finger in. That, of course, plays very well here, too. They’re foreigners, and…

…and they want in, to take advantage of what we’ve cultivated here, or claim to have, or have a political advantage to forwarding that claim.

Exactly. The Driver, who’s such a major character at the beginning of the play, as we’ve been going over it and finding the rhythms in it, he’s straight out of Glenn Beck**. Everything he says, the whole way he is, completely paranoid but also extremely emotional. It’s amazing to me that he wasn’t based on an American person.

You’ve heard of Radio Maria, the hard-right broadcasters. Poles probably don’t need a Glenn Beck.

I’ve been used in our country to a different kind of right wing. People like Rush Limbaugh, who’s a straight-up demagogue. Beck is this newer phenomenon: deeply paranoid in an honest way. With some of the others, of course, it’s coming from paranoia but it isn’t presented that way. Now, with Beck, it’s all about the paranoid, it’s all about their fears. The emotional quality of it is striking to me, that’s why I was so struck by this character. He has these horrible fantasies—again, the play works very well here.

The challenge will be getting the audience to understand the Father Ted figure. As soon as it’s understood that he’s on television, we get it. That puts him in the world that we understand. For the end, we want to make another film, which will also be seen on television. So it seems that salvation and meaning only resides in the media. I think that’s part of what Dorota’s going at. In the value system, there’s some kind of vacuum that’s happened.

Corporatism is the force behind the media onslaught that’s been so utter in the States. You’ve taken up this piece at a juncture when there’s a great deal that’s instructive about Polish experiences. There’s a lot at play there at this time. No telling if astute voices, in literature and theatre, for example, are capable of appraising people of values, faced with jaded media messages and consumerism. We’ll see.

We’ll see. What struck me was the naïve way these characters talk about marketing work. It woke me up to how deeply successful corporatism and consumerism have been here. We’re all speaking the language; we bought it so long ago that we don’t even remember that we did it. It’s become our value system. I love that it reminded me that, oh, right, this doesn’t mean anything. And yet we’ve based part of the whole sense of ourselves and our ethics around it.

You’ve spoken about your foundation in Mrożek, and moving on now to Masłowska. At the Divine Comedy Festival in Kraków this year, the National Theatre from Warsaw played a revival of his Tango, directed by Jerzi Jarocki, who did the piece when it was written in the 1960s.

I haven’t spoken too much about Mrożek in connection to this production, but I feel there’s a straight line from Mrożek to Dorota. She’d probably kill me if she heard me say that. Or maybe she wouldn’t be offended. But I hear it. Particularly the dramaturgy of this play, which is very much like the Mrożek pieces that I did.

How so?

In the machinery of comedy. The way that their written, they’re so funny, really great writing that understands comedy and how it has to be played, with all the things like timing. Yet they are the darkest and most brutal things you’ve ever seen. How they work is that you go in laughing your head off, and you are set up for such a terrible, tragic finale that you’re defenseless. You’re not prepared. That kind of tragic-comic form feels very like Mrożek to me. We’re working on the front end of the play now, it’s so funny. And yet there’s a germ inside it that’s terrible.

There from the get-go, timed in such a way that it can have maximum impact.

Exactly. The other reason—and for me this is always the big reason to pick up a play—is that the actor who’s been the lead actor in my company, his name is Troy Lavallee, he did all the Mrożek with me… I always ask him to play the principal role, he has a very special gift for this kind of work. Incredible physical comic capability, but also the ability to play very serious things. As soon as I read the play I knew this was a part that seemed literally written for him.

How did Troy respond to it?

I sent it to him, with one sentence I said: “This is the next play that we’re doing.” He called me a couple of hours later, and said: “It’s amazing.” He heard it immediately.

I’m working with the director Doris Mirescu, who is doing all the mis-en-scènes. She’s doing the costumes, the set, and also overseeing the video design. She’s an auteur director, uses a lot of video and multimedia in her work. She was in Under The Radar last year, with a controversial adaptation of Husbands by Cassavetes [In 2010, Under The Radar Festival also presented Radeslaw Rychcik’s In The Solitude Of Cotton Fields.] She is Romanian, her parents were political émigrés. It’s helpful to have her perspectives in approaching the design, having a taste of what this world is.

Let me back up and tell you something. I had a hard time casting the Driver. We finally cast someone, and he, after rehearsal, said to me, “Have you met Dorota?” I said “Yes.” “What’s she like?” And I said, “You’d never believe it when you meet her.” When I met her, she didn’t have her punk haircut. She looked like a very nice normal young Polish girl, who you’d never believe in a million years was writing these ferocious texts [laughs]. He said, “Wait a minute—how old is she?” I think she wrote this play when she was 22 or 23. He said, “Oh… I had in mind someone in their 60s.”

There’s everything to be said for popularity, for loud, brash voices that come across. And there’s a lot to be said for the truism, “Who’s really interested in what 23-year-olds write?” His comment bodes well for the work.

It’s incredibly sophisticated.

That’s why it’s good to tell you about No Matter How Hard We Tried. Yours will be the first production I’ve attended of her first play. The work that I do know is what she followed this play with. Completely canny, the TR staging is gorgeous and engaging, and…you are at its mercy at the end. It reaches its finale smartly and honestly. And relevantly.

It’s great to talk. I often feel I’m a bit out in the wilderness in terms of the work I’m interested in.

Perhaps you’re scouting out fresh terrain that we can thank you for somewhere down the track. I’ll tell you later about this Tango revival of Jarocki’s; it’s really killing.

I never went near Tango. I didn’t think it would work in the times we were living in. But maybe now. It’s hard to know.

*Ellen Stewart, who founded La Mama Experimental Theatre Club fifty years ago, died in January at 91. Stewart brought a world of theater work to her stages, including Jerzy Grotowski’s and Tadeusz Kantor’s influential productions, Gardzienice and Scena Plastyczna KUL, and a rousing production of Gombrowicz’s Operetta that included Judith Malina and Hanon Reznikov of the Living Theatre.

**Beck, the radio and television host, political commentator and Mormon, organized the Restore Honor rally on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in summer 2010, on the anniversary of rally at which Martin Luther King’s delivered his “I have a dream” speech.

Paul Bargetto

Founder and Artistic Director of East River Commedia, an international theatre company headquartered in New York City, and the Artistic Director and Executive Producer of the undergroundzero festival. He holds an MFA from Columbia University in Directing and a BA in Drama from San Francisco State University.

Biweekly would like to thank Agata Grenda from the Polish Cultural Institute in NYC for help in pursuing the interview.

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in February 2011 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Paul Bargetto.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.