This year, the plays staged at the festival spoke about distrust of authority and suspicion of the rules that the world abides by. It’s no accident that, in comparison to previous editions of the festival, Gdańsk saw a disproportionate number of Hamlet productions.

The 16th Shakespeare Festival paid a visit to the darker of great William’s works. Even the few productions of his comedies–including Maja Kleczewska’s Tempest–were really far from being genuinely funny. Themes like violence, crime, abuse of power, and insecurity returned like a persistent earworm that we stopped hearing consciously, but it’s still there, lurking.

In Konstantin Bogolomov’s play–recently censored by Russian authorities–Lear divides the country among his daughters, raping a blow-up doll with a microphone. The doll’s skin is covered by the map of said country. Sitting at the dictator’s table are the husbands of Regan and Goneril, their names are intentionally similar to the names of Stalin’s closest collaborators. The comedy form, allowing the director to use even the farthest-reaching associations and ideas, wasn’t able to camouflage the intense disillusionment and bitterness seeping out of Varlam Shalamov’s and Paul Celan’s poems quoted in the play. The world of Lear: A Comedy is a world of elites steeped in madness and rituals of violence, where the innocent have their voices taken away (a vivid scene where Edmund bites off Cordelia’s tongue during a kiss). The play was the most interesting part of the Festival and featured amazing performances by the best Russian actors, including the extraordinary Rosa Khairulina.

Hamlet, dir. Luk Perceval (Germany) Photo: Greg Goodale

The Hamlet that we were looking forward to the most was the brainchild of Luk Perceval from Hamburg’s Thalia Theater and his two frequent playwright collaborators–Feridun Zaimoglu and Günter Senkel. The captivating play had a pure, synthetic form–pretty typical for that particular director–and a clear message. At the center we had Hamlet’s internal conflict (with two actors playing the lead role); the incessant “to be or not to be.” Jammed between outrage, a desire for revenge, and a passive acceptance of the situation, Hamlet acts in an uncertain and disorderly manner. “In the crack between two mouths, I struggle with the words.” The duel between Hamlet and Laertes is the climax of the play and it features dozens of actors shouting lines at the audience. “Decide or draw lots”–but do something–scream the artists. Despite the attractive, cohesive form, fine performances and excellent score provided by Jens Thomas, the production flattens the meanings and implications of Shakespeare’s tragedy and becomes nothing more than a chanted appeal.

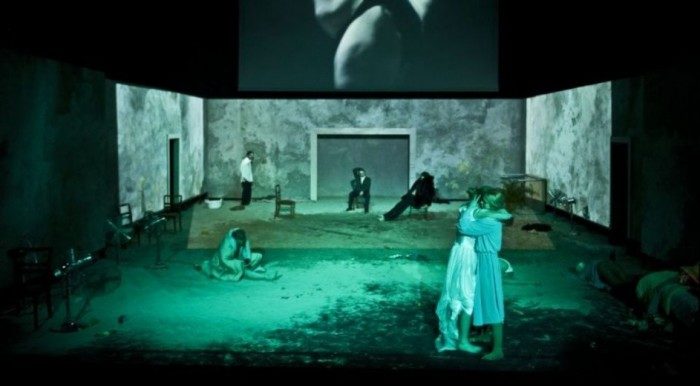

Tempest, dir. Maja Kleczewska (Poland) Photo: Polski Theatre in Bydgoszcz

The productions that were participating in the finals of the Golden Yorick Competition were looking really good. Last season saw an unusually high number of Shakespeare plays produced by the best Polish theatre artists. Maja Kleczewska’s Tempest, despite ambitious assumptions, failed on the formal level as well as an interpretation. This time, the director led the performers astray. The play simply cannot justify the considerable physical effort of the team. The psychodrama offers no catharsis and will only leave the audience tired and impatient. After the disintegration and regression, there is no new creation, no new meanings arise from the ashes.

Macbeth, dir. Marcin Liber (Poland) Photo: B. Sowa

Marcin Liber’s Macbeth depicts reality as steeped in permanent war taking place basically everywhere, a war in which humanity is nothing more than cannon fodder; violence is the only usable argument and the top echelons of power feature a succession of crooks. The women in this world are either prostitutes or full-on butch and trying to be equal to men in their capacity for violence and cruelty. The performances are the weakest part of the production– they’re superficial, lack conviction and energy, they’re simply not up to par with the breadth of the production.

This year’s Golden Yorick was awarded–and rightly so–to Grzegorz Wiśniewski (from the Stefan Jaracz Theatre in Łódź) for his Richard III–a precise and focused production, a play depicting the disintegration of a man who will cross any moral barrier in his pursuit of power. The scene in which the lead playing Richard hands out little flags to the amused audience so they can play the part of the enthusiastic voters was truly uncomfortable in its resemblance to reality. Wiśniewski builds his world with amazing intuition; Richard III, as well as Wiśniewski’s other plays, is full of significant details, nuances, and the play of light and shadow, all of which give it an extraordinary power of expression.

This year, the plays staged at the Festival spoke clearly about distrust of authority, suspicion of the rules that the world abides by and the threat of passivity. It’s no accident that, in comparison to previous editions of the festival, Gdańsk saw a disproportionate number of Hamlet productions–performed by Macedonians, Italians, Germans, Poles, and Danes (it was a Polish-Danish collaboration). In the Italian Amleto the audience members become the eponymous protagonist and observe the events on the stage with an increasingly pervasive claustrophobia, while the actors openly mock their powerlessness and the passive role they were assigned. In this regard, it’s Luk Perceval’s play that stood out among the rest. In his rendition of Hamlet, the crucial showdown takes place not between Hamlet and Laertes but inside Hamlet himself. It’s a fight between inertia and action, conformism, and non-conformism, habit with the need for change. A timeless duel that’s still undecided.

Translated by Jan Szelągiewicz

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in August 2012 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Agnieszka Kochanowska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.