His photography is undoubtfully radiating, soulful, with a hint of edgy energy. Marc J. Franklin is the Principal Photographer and Assistant Photo Editor at Playbill, and his work includes capturing the intangible, ever-fleeting, essence of live performances. As a lifestyle and portrait photographer, he focuses on the artistic process that transcends the technological elements of his craft. Since the Broadway theatres shut down due to the COVID-19 quarantine, Marc J. Franklin has been exploring the history of some of the most iconic theatre photography moments and individuals, to the delight of his thousands of social media followers on Twitter and Instagram @marcjfranklin.

Irina Yakubovskaya: How did you become a Broadway photographer?

Marc J. Franklin: The short answer is – it was the mix of the right place and the right time, with preparation. Theatre has always been close to my heart, I studied theatre at Boston College, but I was pursuing photography as a career. I was a freelance photographer in NYC, I was doing a lot of portrait work. Prior to moving to New York, I had been doing a lot of production photos and headshots in Boston where I studied, and I was doing a lot of client work, lifestyle imagery, and more commercial work. A friend of mine worked at Playbill and reached out to me saying that they were looking for a new photographer, asked if I was interested, and of course I said yes. He said I had to apply right then because they were in final rounds in interviews, and that’s where the preparation came in. Because of all the freelance work, I already had a portfolio, a website, a resume, so it put me in a very good position. Six days after I found out about the job I was officially hired.

IY: Which of these professional experiences was the most beneficial to you?

MJF: When I was on staff at the Bridge Repertory Theatre in Boston, I was their director of social media and multimedia, so I was running their social media and providing imagery and content. That was the first time I’d ever had gotten published in the Boston Globe, it provided me with the ability to, in a very safe environment, explore photography, explore lighting in productions. It really got me to understand my camera, my tools. There is something to be said about taking photos for an audience because suddenly the art isn’t just for you, it is for someone else. It got me really thinking about how to story-tell through my photography rather than just being here with a camera pressing a button. It taught me how to be flexible and put the audience first. In the end of the day, the situation is similar whether it’s for school, for a regional theatre company, or for Broadway: the goal is still the same, which is to capture this very ephemeral thing that is a live performance and make it feel concrete, but do it in a way that the audience who is not there still feel like they are part of the experience.

IY: How do you reconcile that you have to capture something ephemeral, intangible, an experience that is not capturable by definition?

MJF: Historically, theatre photography shifted so much. It is history, creative archiving. At work, not a day goes by where I don’t engage with some form of previous content. In one way, theatre photography is marketing. You want to make sure that a production looks as amazing as possible. It doesn’t matter if you are hired by that production, or if you work for another publication and you are just covering it – you still want to make it look as great as possible, and more than just a look, you want to capture a feeling, the essence, because you can’t hear the music if it’s a musical, you can’t hear that great monologue if it’s a play. You still want to be able to capture what you were feeling in that moment. You want to capture the wonder, the craft, and artistry that all of these artists have put together. Also, you want to do it so that way you are capturing the key moments that will stand out through time. For instance, the lookback gallery for the 60th anniversary of Bye Bye Birdie: we know the iconic telephone number because of these archival [pictorial] moments. You look at the image and you know exactly what number that is. Yes, it’s marketing but it is also capturing the moments and the key images that really let production continue to have a life beyond the stage after that curtain comes down. That’s what I look for when I’m shooting production photos: making those ephemeral moments permanent.

Lucy Liu at the 2019 Tony Awards, by Marc J. Franklin

IY: Your style of photography seems to be subtly subverting the traditional symmetrical frame and color palette. Like a blue note that gently de-centers a harmony, your photographic viewpoint subverts the expectations by offering an unexpectedly unique perspective.

MJF: The notion of style is something that I grapple with a lot. When you see some people’s photos you know it’s their photos: Mary Ellen Matthews [photographer at SNL], Annie Liebowitz… There is also this other group of photographers that aren’t necessarily [inhabiting a specific style]. I know I have a voice; I know how I like shooting, but it is not fine art in the same way that somebody else’s is. It’s taken me a long time to come to terms with it and that it is ok. I love client work. In those instances, you’re bringing yourself to the project, but the client and the work come first. I like creative problem-solving. The way I photograph, a headshot is not going to be the same as an editorial spread in Playbill. That being said, there are key elements to my photos that I really love. I love color, I love it. and it’s interesting that you said ‘blue.’ I usually cool down my photos a little bit because it feels… not somber, but there is a special quality to photos that have a little bluer tone that resonate with me. For example, a bright yellow backdrop adds warmth, but my instinct is to cool it down just a little bit because of my aesthetic. I have a difficult time describing my aesthetic, so in general, it is a photograph in an editorial style in magazines.

Jake Gyllenhaal and Tom Sturridge, photoshoot for Seawall/A Life on Broadway, 2019, photo by Marc J. Franklin

IY: Technology has flooded our lives in the past decade. How do you feel about the role of technology in theatre photography and visual arts today?

MJF: I go back and forth in general. Technology is good, but at the same time, now, especially with Instagram and all other tools, I feel like so many other people want to make their art which is good, their voice comes first. I was talking to Joan Marcus and she was saying the photos that she used to take when way back in the day the 1980s and the 1990s when she was doing it on film compared to what she is taking now because we have so many more options and resources, and there is much more flexibility with innovation and technology. That being said, your tools are your tools. They’re just that. You can take a really great photo without the fanciest camera. I never want the technology to become the hindrance. At a certain point, yes you do have to step up your gear, and that is part of your process. You can’t do a huge editorial spread using a camera that doesn’t have the technological capabilities. That being said, you can still grow. I see people take amazing photos with an iPhone. I shot with a Canon Rebel, which is an amateur DSLR, for the first six years of my career, because I couldn’t afford anything else. I used that camera and I taught myself how to edit in Lightroom and Photoshop to enhance my photos. I also taught myself my craft: how do I engage with people, what do I look for with the eye, what are the other elements I can control if it’s not necessarily having the most up to date technology. I can control the light, I can art direct. For me, it has always been this way: the art comes first, the craft comes first. From there, you step it up. As you get more gigs – save the money from gigs so that you can eventually get that new camera or that new lens. I definitely see how people can buy their way into a career with art, like buying the best paintbrushes or the best camera, but you can still see that you need to know what you’re doing. Phones have so much capability, and still, people aren’t taking great photos because they don’t know how to use the tools. In addition to technology, you need craft, skill, dedication, and practice, to make the art stand out.

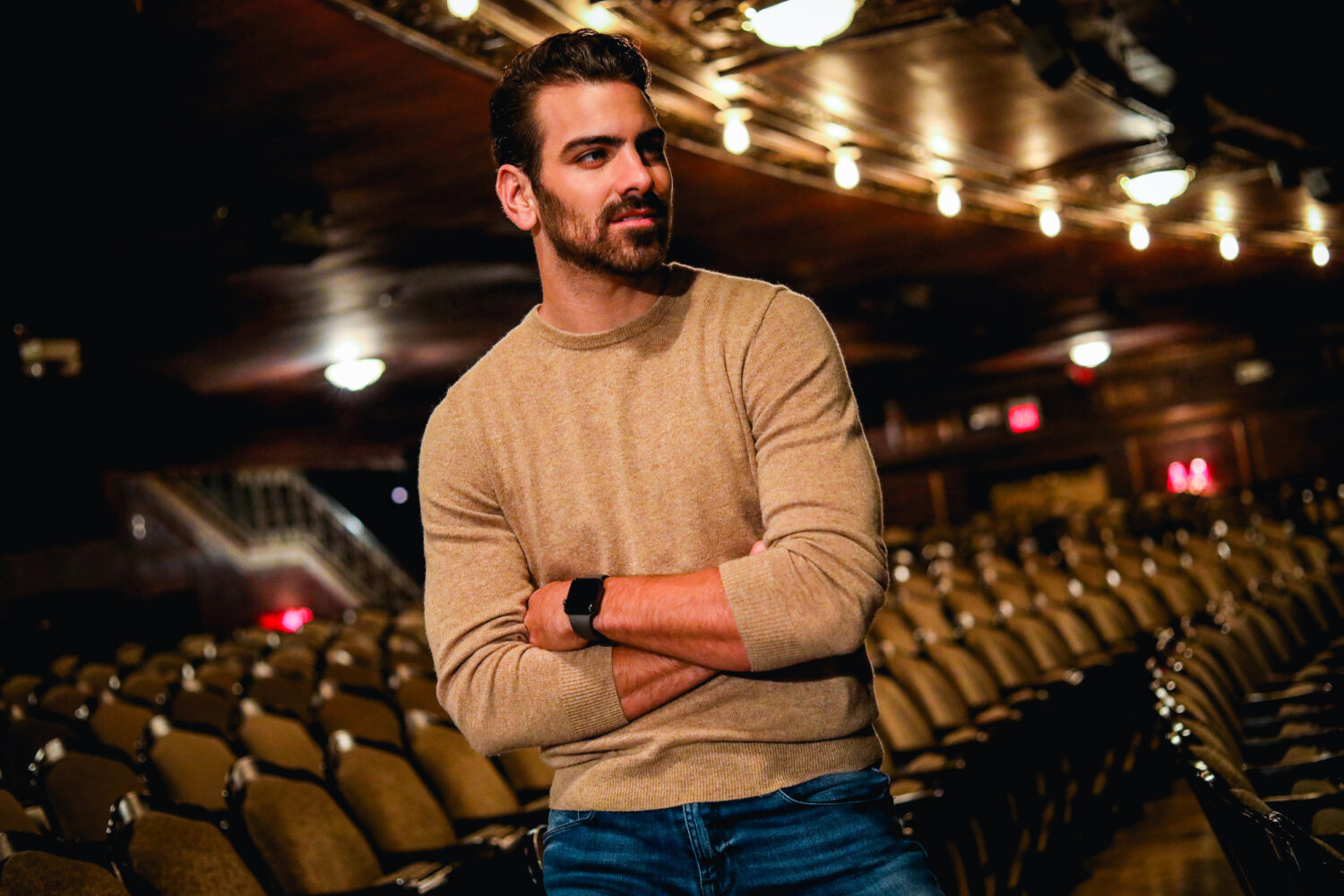

Nyle DiMarco, photo by Marc J. Franklinmark

IY: What current or upcoming projects are you working on now?

MJF: I have personal projects and things that I want to do when Broadway comes back [from the quarantine due to COVID-19 pandemic]. I miss taking photos and portraits. One of the other aspects of my job as the principal photographer and assistant photo editor at Playbill is to reach out to artists and interview them about past projects or fan art. Now I get to focus on the story aspect of the job rather than the image-making. I’ve been doing the series with prominent production photographers where they get to go back and pick their fifteen to twenty favorite photos they’ve taken. We get to look not only at the image but at their process. Being able to uplift the community in that way has been fun. It is making me a better storyteller beyond just the images. Just before the pandemic, as a photographer, I was experimenting a lot with how I shoot, what I shoot with, where I put my light, so that’s something I’m excited to get back into when this is over. I just want to photograph more and better than I ever have before. I want to celebrate Broadway at large. The process is the thing I love the most too. In interviews with actors, we want to hear about how they delve into their roles. That is what a feature is, especially when it comes to entertainment. So, exploring the process with my own colleagues is really exciting. I am getting to know my collaborators and colleagues in a new creative personal way. Not only selfishly for me it’s really fun, but we are able to gift it back to our audience at Playbill.

IY: Is there a particular element of your own process, as a photographer, that you wouldn’t mind sharing?

MJF: At the core of my artistic process is capturing the heart of the subject. To do that, I strive to humanize the photoshoot experience. Every photoshoot is different, and I always try to create a concept that works best for the needs of the project, but most importantly, I want to strip away the artifice of what a “photoshoot” is. Rather than maintaining the structure of photographer and subject, I always create an atmosphere in which we can just be two people, making a project together. I try to start off by chatting about life outside of the photoshoot, I play music, I ask my subject for ideas and input, etc. I find that by taking the weight off of the photoshoot experience, it allows the shoot to be a creative collaboration and a much more enjoyable process.

IY: During this pandemic, many people turned to exploring their hobbies and interests, and I am sure that your view of technology vs skill will be appreciated by amateur photographers all over the world. Speaking of the pandemic: what is your most unexpected positive outcome of the quarantine so far?

MJF: I think the community aspect of it. Broadway… it’s hard. Usually, it’s day in and day out, it’s so much work. The Broadway community is small. Part of it is NYC – you see them make their star appearance on the opening night, and then you see them on the train the very next day, all because NYC is so small. What the pandemic has done is it took away that typical structure: the star vs the press, or the director vs actor. It’s taken away that, and we’re all just people. I’ve sent and gotten so many messages to and from people just checking in. Because we are always constantly working, we get to know each other from that front, but when you take away the work aspect of it, you’re just left with these people who are all in this together to make one common thing which is theatre. I think that’s been a really positive unexpected thing. I’m worried about many of my friends who are artists and who can’t work, and they’re also worried about me. So, getting a friendly check-in from somebody I photographed goes to show that community comes first. We’re all adapting, we’re into our second month of this quarantine and as this continues, we’re learning how to be and how to care for each other. There’s not a day that goes by when I see somebody encouraging people to donate to a charitable organization or fund, or to an individual who makes art pieces and needs help. This is a dark time, but it is showing the best of humanity.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Irina Yakubovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.