Anyone looking for evidence of just how devastating the COVID-19 pandemic has been to Australia’s performing arts industry need look no further than its flagship company, Opera Australia.

Only last year it was boasting an operating surplus. Last month, however, Chief Executive Rory Jeffes announced an organizational restructure, which the industry union claims could result in up to 25% of permanent staff losing their jobs.

The aim of this restructure, employees were told, was to better align the organization to the changing environment of COVID-19 with a new operating model. But what, exactly, should that model be?

Certainly, redundancies were inevitable. Jeffes had already called an abrupt end to the company’s 2020 season. Even where governments have allowed entertainment venues slowly to reopen, the economics of “socially distanced” opera-going simply do not support the budget models of old.

The Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance, however, has described the proposed changes as “a disgrace,” citing a lack of staff consultation among other grievances. In response, a spokesperson for Opera Australia said last week the 25% figure refers to administration staff only, and consultations are happening with employees in the rest of the organization.

The dispute, now before the Fair Work Commission, will be followed with interest and concern across the industry. Opera Australia is Australia’s largest and most lavishly publicly funded performing arts company and many livelihoods are at stake.

Musicians from Opera Australia at a protest rally in March. PC: Joel Carrett/AAP.

A City Art Form

Opera is especially exposed because it is so closely connected to the places where pandemics have the greatest impact — large cities. Opera is an urban art form par excellence. By the mid-19th century, it had become a principal medium through which burgeoning urban populations might hear and see stylized representations of their lives (albeit filtered through the lens of historical or mythic subjects). It’s not for nothing, for instance, that so many operatic heroines die of “consumption,” a preeminently urban disease.

Now, however, under the shadow of COVID-19, the future of the city itself is under question: the rise of video platforms like Zoom seems to make the necessity of “being there” no longer a necessity. This idea has been refuted by others who highlight the human yearning for togetherness. The general manager of New York’s Metropolitan Opera, Peter Gelb, similarly has said that while it may be soothing to watch opera streamed at home, it is ultimately a “one-dimensional experience.”

Nevertheless, with theatres unable to return to full capacity for the indefinite future, and public funding bodies becoming strapped for cash, a return to anything like our pre-COVID operatic culture is unlikely. The current crisis does, however, offer a chance to think afresh about opera’s place (literally as well as figuratively) in our society.

Do we now have an opportunity, as Michael Volpe, the director of London’s Opera Holland Park, has suggested, “for the opera ecology to remodel itself into something that’s more cost-effective and fleet of foot?”

Volpe calls for an “opera socialism.” What he is advocating is a return to something closer to opera’s own origins as a performance culture more directly connected to, and supported by, the local communities in which it is based.

Local, Not Global?

Until the pandemic hit, Opera Australia worked within an industry dominated by global commerce in “star” singers, conductors, and directors, typically managed by a system of international artist agencies.

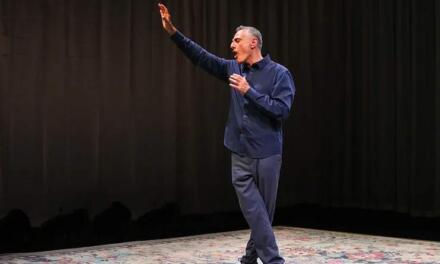

Teddy Tahu Rhodes performs during the final dress rehearsal of Opera Australia’s Il Viaggio a Reims in Sydney last year. PC: Dan Himbrechts/AAP.

Now that system is in a state of collapse. In recent weeks, two of the largest classical music agencies, the US-based Columbia Artists Management and the UK’s Hazard Chase have announced they are shutting their doors.

Is it now time for us to reconsider the need for a national opera company in turn? The economic impact of Opera Australia touring main-stage productions, even just to Melbourne, puts it under significant operational stress. But it also doesn’t allow the company to develop strong local connections outside its Sydney home.

A fully decentralized model might, in fact, be better able to support the operatic “ecology.” Many smaller professional, semiprofessional, and amateur operatic companies already operate successfully in our major metropolitan centers with little or no public funding.

They are also currently much more likely than Opera Australia to mount productions of new Australian operas, or works outside the mainstream repertoire.

While Opera Australia’s Artistic Director Lyndon Terracini said back in 2014 that he was “desperate to create new work that is relevant to a significant audience,” he also conceded the company’s operating model does not give it the financial resources to do more than produce mostly a narrow range of traditional works, supplemented by productions of commercial musical theatre.

Maybe it is now time for both federal and state governments to consider focusing more on a civic based or “ground-up” institutional foundation for opera rather than sustaining a nationally based “top-down” one.

The 2016 National Opera Review ducked considering such a possibility. But a new parliamentary inquiry into Australia’s creative and cultural industries and institutions is underway. Now is the opportunity for us to contemplate a new place, and indeed new places, for opera in Australia.

This article was originally posted on theconversation.com on September 8, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Peter Tregear.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.