In March 2020, Colden Lamb had the opportunity to sit down with award-winning costume designer Judith Dolan and ask her about her work on multiple productions of Candide with legendary director Harold Prince. The following are highlights from his interview . . .

“I think the hardest thing in the world to do is a musical and I have many fellow designers who would agree with that. It is the hardest art form to pull off.” – Judith Dolan

Based on Voltaire’s 1759 satirical novella Candide, the 1956 operetta Candide by composer Leonard Bernstein and playwright Lillian Hellman tells the story of a young man and his search for happiness in “this is the best of all possible worlds”. Although the original Broadway production had a lackluster run, many critics consider Candide to be Bernstein’s best score. In 1973, The Chelsea Theatre Center of Brooklyn persuaded producer/director Harold Prince to helm a production of Candide with a new libretto by Hugh Wheeler and additional lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. This version transferred to Broadway where it ran for almost two years. In 1982, the New York City Opera (NYCO) asked Prince to create a version of Candide for them. In 1997, a Broadway revival of Candide based on Prince’s NYCO production opened at the Gershwin Theater and earned Judith Dolan a Tony Award for Best Costume Design. In the Broadway Souvenir Program Ms. Dolan wrote:

One of the most important issues for me was how to convey the charm [of Candide] without losing the satiric edge and wit of Voltaire’s work. The satire felt so fresh and current. The contemporary influence of artists such as Bernstein, Sondheim, Wilbur, Wheeler, and others was no doubt a part of this, but this “collaboration” with Voltaire that spanned two centuries demanded a fresh approach. The circus is a particularly rich visual metaphor which crosses national boundaries and traverses time . . . elements that are useful for this production of Candide. My historical research encompassed traveling shows of all kinds and music hall conventions of the early part of this century, as well as theatrical presentations of the [Spanish] Inquisition and the carnival atmosphere surrounding the French Revolution. Ultimately, I hope that the costumes for Candide convey some of the joy of the production without losing its critical edge.

This past March I had the privilege of interviewing costume designer Judith Dolan. We discussed her approach to designing the costumes for Hal Prince’s productions of Candide beginning with NYCO in 1982, and her collaboration with the legendary director/producer.

Colden Lamb: How did you acquire the job for Candide in 1982?

Judith Dolan: I got that job through Hal Prince. I was designing a soap opera at the time. That job was ending and I was moving on. I was applying for more theater work by sending out letters to producers and directors through Backstage. At first, I didn’t know if I should apply to Hal Prince, you know, he’s too big. Who am I? However, it was the Prince Office who got back to me, nobody else did. They asked me if I would be interested in an internship and I said yes, not having a clue what it was. And it was out of those first interviews, I got to do three shows, one right after the other and one of those shows was Candide for New York City Opera in the early 80s. The other two shows were Merrily We Roll Along and an opera called Willie Stark with Houston Grand Opera. That was the first show I did with Hal. Willie Stark was one of those cases in which I was sitting there at the first dress rehearsal at Houston Grand Opera (and this is true) when I realized it was the first opera I’d ever seen in my life! I had very limited experience in theatre. I came from a family of steelworkers, so I saw an occasional movie but that was about it. I have no idea how I ended up in the theatre but Willie Stark was my first opera (but I didn’t tell Hal Prince that).

CL: Did you discuss or research costume designers who designed previous productions of Candide?

JD: No. I try not to be influenced by other designers on productions, especially those that might be called seminal. It’s not that I don’t respect their work, it’s just that it doesn’t help me create something original.

CL: You have stated that your costumes for Candide were based upon late 19th-century carnival, circus, and burlesque shows. Was that concept your idea, or Hal Prince’s idea, or both?

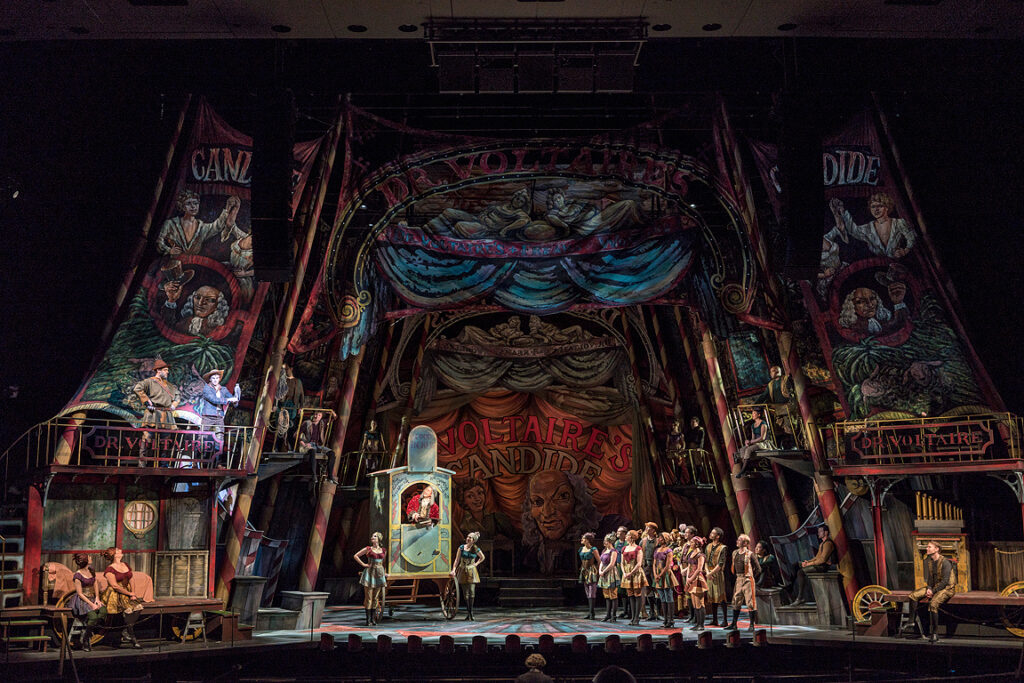

JD: For the NYCO production in 1982, Hal wanted it to look like a down-and-out traveling show, so the colors and banners were all green and grey; a rustic and dark take on it. Then when it went to Broadway, which was a big stage, Clarke Dunham (the set designer) used bolder colors making the Broadway production more circus-y by default. When I saw the scale that Clarke Dunham was doing, I knew that my funky little down and out “mummers” from 1982 would not be seen on the stage. I had to punch up my costumes in order to compete with the beautiful but complicated scenic design. I knew I had to go to a bolder and stronger color range for my designs on Broadway. For the most recent production with NYCO that I did with Hal, he wanted to bring back the 1982 color palette of darker colors. I re-designed everything to pull it down and Hal was very happy with that.

Jay Armstrong Johnson, Gregg Edelmann, and members of the New York City Opera in the 2017 production of Candide directed by Harold Prince. Photo © Sarah Shatz.

CL: Why didn’t you design the costumes based on the time period of the novella—the 18th-century? Why no powdered wigs, no giant Marie Antoinette panniers?

JD: Well they did that before, in 1956, and it failed. However, that wasn’t Hal’s concept. He told me that he wanted it to look like a school boy’s prank, so it had to look a little more light-hearted and flippant. In order to achieve that, and to capture Voltaire’s comic satire (because it is a dark comedy), I made it an agenda for myself to offend every single ethnicity, person, and place I could think of. It was equal opportunity satire and I would try all sorts of stuff. Once you do that and when everyone becomes a target, you can enter into the festivity of the satire wholeheartedly. The smartness of my designs were really important to me. In 1982 we did not have a very large budget. I embraced the limitation and found joy in it. We were under the gun and I remember on opening night I was stitching aprons for the final scene. Hal Prince came to the costume shop and asked, “What are you doing?!” I said, “I’m sewing! You said you wanted white aprons!” He started laughing and said, “Well, you wouldn’t see Florence Klotz stitching.” I said, “Well do you wanna see your aprons?!” We had a great kind of banter back and forth. In 1982, I wanted everything to look like it came out of an old opera trunk. NYCO had a lot of Wagnerian helmets and crazy tunics which I decided to use for the Westphalia battle sequence. When we recently remounted the show a couple of years later, we had to re-make the costumes all over again because the costumes were burned in a warehouse fire. It was really sad because there were some really beautiful old archaic opera treasures.

CL: The 1997 production of Candide added acrobats and stunt artists. Did you have to make changes to the costumes to accommodate them?

JD: The ensemble costumes of the show were all designed in each production specifically for the dancers. For instance, the ensemble women’s clothes were all built as ballet costumes. Hidden in the seams of their costumes were elastics so they could pull up and pull down. They were all hand-dyed silk-satins to get that soft patina, but they were built of heavy construction so they could take abuse. When I had acrobats in 1997, I had to get special shoes and I had to do a couple of other special things. For the ensemble men’s costumes, the shirt’s were knit, things would stretch and move, it was all built to be danced in.

CL: I wonder why the 1997 version of the show wasn’t better received?

JD: I have often wondered that too. It had so many good things in it and about it. I personally think it was in the wrong space. That particular theatre was just too big. It lost its joy and intimacy. In a big theater, you have to compensate, you have to use big gestures and for something that’s quirky, that’s hard. It lost its quirkiness. The Gershwin Theatre was huge and we all knew it. It would have been better in a smaller theater. (Looking at a picture from the 1997 Souvenir Program) I mean, look at the stage, it’s cavernous! The quirky costumes got lost on the big stage, you couldn’t really appreciate their goofiness. I think the hardest thing in the world to do is a musical and I have many fellow designers who agree with that. It is the hardest art form to pull off. To do a new musical or a new approach to a musical is really tough. I have such respect for anyone pulling off a good musical because it’s very difficult.

CL: One of my favorite costumes you created for Candide was The Lady of Oporto (The Lady of Oporto is a local Madonna) for the “Auto-da-fé” sequence.

JD: I love that costume, too. She was a Madonna. I called it “The Infant of Prague” look. I added a globe on the top of her head, and a giant blue and gold hoop skirt. I also added a dancing Jesus puppet to that costume. I wanted to pay tribute to the religious iconography as well as make her as big as possible. My sister has the sketch for that costume because she thought it was so funny.

CL: I really missed seeing that costume for the 2017 NYCO production because that little section with The Lady of Oporto was cut.

JD: Another thing that got changed in the last production that I missed were the original costumes for the Old Dons in the “Easily Assimilated” number. I originally had them in long red underwear and really bad beards.

CL: At NYCO in 2017 the Dons are all in grays and greens.

JD: Yea, Hal didn’t want the red underwear. When we opened in 2017, Hal was perplexed. He said it didn’t work this time and I felt like saying “Well…then listen to your designer!” The red underwear told the audience that these were old men with droopy drawers, it didn’t have the same effect with the grey underwear.

Linda Lavin and members of the New York City Opera in the 2017 production of Candide directed by Harold Prince. Photo © Sarah Shatz.

CL: Could you tell me more about your designs for the character of Dr. Pangloss? I love that when Pangloss arrives in Lisbon, he is wearing a patchwork outfit with a hump on his back. What was your inspiration for this?

JD: The inspiration for that costume was for Pangloss to look like a Punch and Judy puppet, another theatrical callback. That costume was constructed all in one-piece with quite a bit of velcro since the actor playing Pangloss had to underdress as Voltaire for an instant fast-change.

CL: Did you also design or have any input on the wigs and hats for Candide?

JD: Yes, but sometimes I didn’t have much control. In 1982, we used the NYCO hair and makeup people and they had their own approach. I didn’t think it translated well when it was recorded for (Great Performances on) PBS, as it looked too extreme. And Hal had his input too because he wanted his characters to look a certain way. And we’d have different wigs for different actors. For example, Erie Mills who played Cunegonde in 1982 had a blonde wig, Meghan Picerno in 2017 was a brunette, while Harolyn Blackwell [1997] used her natural African-American short style—her hair was so absolutely darling we didn’t have to do anything!

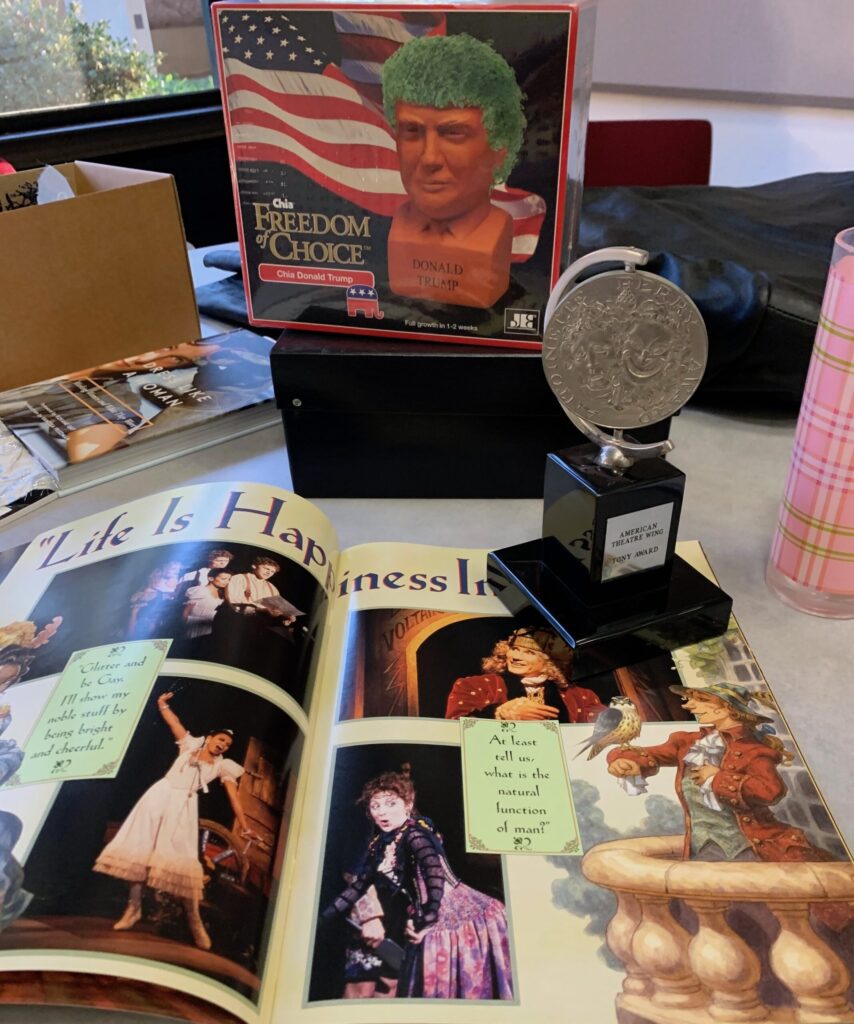

CL: I read in Hal Prince’s book, Sense of Occasion, he wanted to make his recent 2017 NYCO version of Candide a personal statement against the politics of Donald Trump. Was that why the colors for that production were darker and more bleak?

JD: I think that was important to him for the ending: he wanted the ending to be very austere. I want to show you something (she gets up and grabs something off from her bookshelf). This was Hal’s opening night present to me (She proceeds to place on the table a Chia-Pet of Donald Trump). This is the kind of humor we had. He’s handed me some really nice opening gifts but this time he handed me this.

Dolan’s opening night present from Harold Prince (top center), Dolan’s Tony Award for her costume design for Candide (right), and a souvenir program from the 1997 production (bottom center).

CL: Do you have any particularly fond memories from the many versions of Candide you have done?

JD: Oh I love them all, I know that sounds terrible but it’s true. I’ve a particularly fond memory of the Broadway group. There was a feeling of ensemble to it all. I was told that when I won the Tony that year, the ensemble was sitting in the green room, I think they had just performed, but I heard they went bananas when they found out I won. And that’s what it felt like, it felt like you were doing it for everybody. I think I even said in my acceptance speech that this was for them. I also thanked Hal Prince for his many acts of faiths over the years towards me and that was in reference to the “Auto-da-fé” which means “act of faith”. I thought that was important.

Judith Dolan. Photograph by Manny Rotenberg.

Judith Dolan has designed costumes for several productions for director Harold Prince including Candide for which she received a 1997 Tony Award. Another collaboration with Mr. Prince, the musical The Petrified Prince, earned her the Lucille Lortel Award and a 1995 Drama Desk nomination. Other theatrical credits include costumes for Andrei Serban’s production of The Miser for the American Repertory Theatre, Christoph Von Dohnányi’s interpretation of The Magic Flute for The Cleveland Orchestra, Idomeneo for Wolf Trap Opera and the original Broadway production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. Her designs have been seen in numerous companies in the U.S. and abroad including Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, Theatre Clwyd in Wales, The Old Vic, The Kennedy Center, The Brooklyn Academy of Music, The Shakespeare Theatre in Washington D.C., The Goodman Theatre, The Alley Theater, The Mark Taper Forum, Hartford Stage, New York City Opera and the Houston Grand Opera. Recent Broadway work includes the award-winning musical Parade and Hollywood Arms. In 2007, she designed costumes for LoveMusik, directed by Hal Prince, for which she received Outer Critics and Drama Desk nominations for Best Costume Design. In 2014, the New York City League of Professional Theatre Women awarded her the Ruth Morley Design Award for her career achievements and leadership in design. Judith Dolan has an MFA in Costume Design and a Ph.D. in Design and Directing/Theatre History and Aesthetic Theory from Stanford University. She is currently a Distinguished Professor and Head of Design in the Theatre and Dance department at the University of California San Diego.

Colden Lamb is a Southern Californian based actor. He is also a graduate of San Diego State University. coldenlamb.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Colden Lamb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.