Sweat, by Lynn Nottage, is a cautionary tale about how the effects of poverty, or the threat of it, breeds divisiveness among the middle class and poor. Thanks in large part to the actors’ credibility in their roles, Left Edge Theatre’s “COVID-19 social distancing” production on Zoom goes from being quietly engaging to thrilling to watch by the time we enter the second act.

Sweat, first performed in 2015 and destined to be an American classic, centers its story on the friendship of three women (played by Serena Elize Flores, Jill Zimmerman, and Lydia Revelos). Cynthia, Tracey, and Jessie are fellow factory workers and friends, who drink together at a local bar that caters to union workers. Stan the bar owner (played by Mike Pavone), does his best to maintain a congenial atmosphere for his customers. External influences prove beyond his control; a confrontational environment sets in when the factory goes through major management changes.

Oscar (played by Anthony Martinez), Stan’s bar assistant, confides in Tracey that fliers were posted near where he lives that advertise job openings at the factory. Tracey does not believe job openings are being advertised without her knowledge, i.e., current union employee knowledge. Tracey becomes unsettled that the flier Oscar holds in his hand is written in Spanish. Oscar is Colombian-American. Tracey is white American of German descent. Oscar ignores her hostility towards him and asks if she could help him get an in. Tracey is all too clear that she will not help him. Jobs are not for outsiders. Her dad worked there all her life, she has all her life, and now her son does, etc.

Meanwhile, the social dynamics abruptly change between Cynthia, Tracey, and Jessie after Cynthia gets promoted to a management position. Tracey warns Cynthia is it not possible for factory staff to get a promotion into a management position (“management is for them, not us”). Cynthia, who is African-American, does get the job. Tracey, possessed by envy, spreads rumors that Cynthia only got the job based on affirmative action.

Oscar is right about jobs becoming available. It unfolds Cynthia betrays her friends, and incidentally her son (played by Sam Ademola), who also works in the factory, to side with Management in a negotiation to cut salaries and benefits. On the one hand, it is sad and demoralizing to watch middle class workers, who bravely refuse to accept reduced compensation, while higher-ups reap in profits, lose their jobs. On the other, it is easy to understand why people unfairly deemed “outsiders”, singled out for poverty due to racism or xenophobia, do not feel solidarity with the plight of predominantly white union members and cross picket lines.

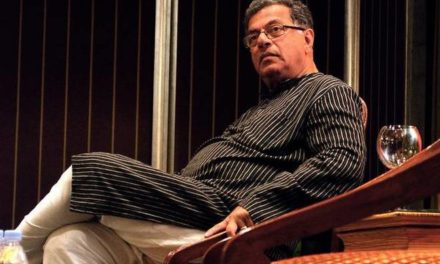

Chris and Jason, played by Sam Ademola and Skylar Bird, work in the same factory their moms do. Photo courtesy of the Left Edge Theatre.

Nottage writes a story that speaks to the truth of the human condition. In Sweat, labor negotiations marred by self-interest weaken one’s leverage to succeed, as well as creates repercussions for family, friends, and community; directed here by Argo Thompson, the audience shares in the play’s underlying wish that a diverse group of people can learn how to organize effectively to create economic stability for them all.

It seems wise that Sweat does not attempt to factor in how heated national debates regarding abortion, gun laws, climate change, and healthcare—to name a few of many complex topics that Republicans and Democrats take opposing stands—further undermine the potential for middle and lower classes to join together based on mutual economic interests.

It is curious that drug and alcohol abuse are frequently mentioned but rarely acted out in this production. Jessie, often drunk, is perhaps the one character chosen to embody the other cast members’ struggles with addiction. Tracey’s son Jason (played by Skylar Bird) embodies political extremism after he loses his job and becomes a Neo Nazi.

Working on Zoom creates artistic challenges. The production manager (Vicki Martinez) and design crew work these limitations to the show’s advantage. One actor (Corey Jackson) plays both Evan and Brucie. Johnson is an adept actor, so it only takes a minute or two into the dialogue to determine which character he is playing. In Act Two, Scene 6, there could a screenshot or two of characters not talking to clear up some brief ambiguity about who is in the room. The climactic scene where violence breaks out, the actors are physically all together on the stage. It is a gripping and heartbreaking scene that also carries with it (L.A. had a brief reprieve of social distancing requirements) hope of theater returning live.

The ticket price of this show was reasonable at the cost of $10 to $25. Many people are unemployed and cannot pay for tickets at this time. For those of us who can pay, getting to explore theater productions from across the nation, and world, is a worthwhile pastime that fund theaters while they are shut down. There is also the added plus that those who do not normally have access to theater, or cannot afford the ticket price of live theater, get exposure to new plays like Sweat.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Heather Waters.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.