In Marathi literature, one finds a strong tradition of Dalit literature, including autobiographies by both men and women. Urmila Pawar, a Dalit woman writer in Marathi, has been writing on Dalit culture and gender issues for the past twenty years. Aaydaan is a play based on her autobiography (published in 2002).1

The play, conceived by Ramu Ramnathan, is directed by Sushama Deshpande—herself a journalist, writer and actor. Sushama has been performing the one-woman show Vhay Me Savitribai, based on the life of the 19th-century social reformer Savitribai Phule, for the past 25 years. Deshpande also has had a personal association with Urmila Pawar since the 1980s through Maitrini—a women’s group. Awishkar, a theatre movement active for the past 46 years, has always welcomed and encouraged new ideas, new experiments in the field of theatre, and has provided opportunities to young theatre personalities. And thus came about this two-hour play, produced jointly by Awishkar and Anjor.

The term Aaydaan refers to items made from bamboo, such as trays, baskets, and hand fans. Pawar’s mother used to create Aaydaan, these bamboo artefacts. Urmila discovers a similarity between the weaving of bamboo strips and words that weave a pattern. Like Aaydaan, Urmila weaves through words the life charts of many Urmilas, Vimalas, and Sushilas representative of Dalit women. Aaydaan charts the journey of Urmila Pawar from the Konkan region to Mumbai—as a Mahaar, as a Dalit and as a woman who challenged the conventions of both caste and gender to emerge as a strong literary voice. Weaving is the metaphor of Pawar’s Aaydaan. Pawar says, “My mother used to weave Aaydaan . . . I find that her act of weaving and my act of writing are organically linked. The weave is similar. It is the weave of pain, suffering and agony that links us. . . . When I asked my mother about ‘motherhood,’ she replied in one word ’sacrifice’ with pain on her face.” The play follows the book’s narration—starting with Urmila’s being born in Konkan and her gradual journey to another consciousness.

About writing the memoir, Urmila has said, “I was a rebellious child and had numerous fights with my mother while growing up. But by the time I wrote this book, I felt I had taken her place. Like her, I was attempting to make the most of my life in a patriarchal society; I had lost my husband and my son and my two girls misunderstood me because they could not understand my need to have a life beyond home. It’s as if our lives had been juxtaposed.” The socio-political scene in the seventies in Maharashtra was that of radical change. We see in Pawar’s work the sharing of awakening of consciousness of the times, surpassing her personal tragedy.

The play opens with scenes from Urmila’s school days, showing the caste discrimination she experienced at an early age and the way in which poverty becomes a matter of humiliation. Aaydaan charts the journey of Urmila as a schoolgirl; her memories of her father, who wanted his girls to be educated; her attempts to avoid going to school—hiding her uniform, and so forth. Incidents like the teacher asking Urmila to collect cow-droppings, her refusal, and her consequent beating at the teacher’s hands underline societal attitudes. Her mother questioning the teacher about the same reconciles Urmila to her mother and establishes her mother’s character. However, several factors make her feel inferior to her classmates. She narrates an experience with a Muslim family who condemns her as ‘Mahaar.’ Her later conversion to Buddhism was an incidence of self-assertion for her, like for many Dalits.2

Urmila’s studying in high school, her teasing by boys, and her retort establish her independent and fearless character. She describes incidents about her courtship and marriage and good experiences after her marriage. She also narrates her experiences of caste discrimination from her servant, from a BMC (Bombay Municipal Corporation) member, and so on.

The play revisits incidents from Urmila’s personal life: the loss of her brother, the birth of her son followed by two daughters and, at the same time, her journey through social life. Inspired by Dr. Ambedkar’s speeches and thoughts, Urmila begins writing short stories, wherever possible. She aspires to graduate after coming to Mumbai and receives her husband’s encouragement. However, when she wishes to do postgraduate work, he shows his displeasure. Urmila recalls the congratulations she received from Dr. Bhalchandra Mungekar for the achievement her husband so disapproved of. Urmila portrays the problem of a wife successful in public life and the husband who can’t come to terms with this fact through instances between her and Harishchandra.

Eventually, Urmila was introduced to a women’s organization, ‘Maitrini,’ through a friend, Heera Bansode. The experience of working with this group helped her to see women as persons, as human beings. Urmila narrates various experiences while working with the Dalit women’s movement, wherein she interacted with highbrow Dalit families who were hiding their identities to obtain social approval. She also interviewed women who worked with the Ambedkarite movement.

Urmila faced a trauma in her personal life—losing her son. She touchingly narrates her efforts to reconcile herself to his loss by recollecting stories like that of Tathagat (Buddha) asking Gautama to procure mustard seeds from a house where there had been no death, as she tries to console herself over her son’s death. Urmila immersed herself in her writing to fill the vacuum left by the loss of her son. At that point she remembered that she was irritated with her mother weaving Aaydaan all the time, unable to understand that it fulfilled her mother’s need to remain occupied.

She also narrates the trauma of her mother’s death, followed by her breaking off her marriage, and her husband abandoning the daughter and Urmila. Finally, her husband took to drinking and eventually died.

There are constant references to religious orthodoxy and socio-political changes; for example, Urmila refers to the Manusmriti, which is said to have imposed many restrictions on women and also framed a caste system. This explains her further act of conversion to Buddhism to renounce the caste-based Hindu religion, following Dr. Ambedkar. Like for many Dalits of the period, this act led to personal growth in Urmila’s case. The next step was her discovery of feminism after moving to Mumbai, adding to her growth.

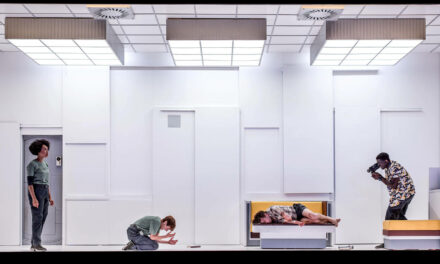

Thus she charts her journey from a Dalit girl in a village to a woman in Mumbai with much greater awareness and a heightened consciousness. This journey becomes vivid and touches a chord with the audience due to a powerful script and direction and intense actors—Nandita Dhuri, Shubangi Savarkar and Shilpa Mane.

The play meets the challenge of retaining the dialectic nuances of the original writing. The choice of the three young actors is superb, and the director has skillfully explored the strength of their acting skills. The three play multiple characters, including that of Urmila, who is enacted by all three at different points. In performing, they interchange roles, gracefully and instinctively. Through the sequences of scenes one gets an exact portrayal of Pawar’s narration.

References

- Urmila Pawar, Aaydaan, 2002.

- In the 1970s, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar called for mass conversion of the Dalits to Buddhism, which according to him helped the Dalits raise their self-esteem and facilitate their growth.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hemangi Hemangi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.