Ilya Demutsky’s Anna Karenina, with choreography by Yuri Possokhov, was a central event of the Joffrey Ballet’s sixty-third season. The show was created in collaboration with the Australian Ballet. Ten performances took place in Chicago from February 13 to 24; in May 2020, the ballet will premiere for Melbourne audiences. Before the world premiere, composer Ilya Demutsky spoke with me about his work with the choreographer, reminisced about his experiences in America, reflected on minimalism in music, and talked about why contemporary Russian composers’ music isn’t performed in the United States.

Who’s who in modern classical music: Ilya Demutsky. A Russian composer and conductor. Born in Leningrad. A graduate of the Glinka Choir College and the Saint Petersburg Conservatory (class of professor T. Khitrova). Fulbright scholarship winner. Studied composition at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music (class of professor David Conte). Has written more than one hundred and fifty musical works, including operas, ballets, symphonies, chamber music, and film scores. Winner of international music competitions. “Golden Mask” winner (2016) for his music for the ballet A Hero of Our Time. Winner of a European Film Academy award (2016) for his music for K. Serebrennikov’s film The Student. Benois de la Danse laureate (2017) for his music for the ballet Nureyev. Artistic director of the vocal ensemble Cyrillique.

The last months of 2018 were stressful for Demutsky. In November his opera Black Square had a very successful opening in Moscow. The performance took place in the Novaya Tretyakovka, and Kazimir Malevich’s painting by the same name became the central character (the leading man, they joked backstage).

Sergey Elkin’s conversation with the composer began with congratulations and questions about Black Square.

Are you happy with the way the opening night went?

Yes, of course. I think the project succeeded.

Why didn’t you reveal who the director was? Why all this secrecy when behind the scenes they said openly that it was Danila Kozlovsky—and he himself doesn’t seem to have denied it?

I’m keeping silent on this only because the director requested it. As long as he doesn’t announce it, to me, it doesn’t seem right to say it for him.

One more “why.” Why is the opera in English? Why take on the additional challenge of translating Kruchenykh and Khlebnikov?

The original idea of the opera is the producer Igor Konyukhov’s. The opera was born from a commission for Konyukhov to translate Aleksei Kruchenykh’s libretto Victory over the Sun. It was a student project. A few years ago, Igor founded the New Opera theatre in New York… Black Square was a completely spontaneous idea. It doesn’t really make sense to get hung up on the opera’s language; it’s just because my cocreators—the authors of the libretto, Olga Maslova and Igor Konyukhov—live in America, and English is the language they write in.

In one interview you said that you hope the opera will be shown in other cities and countries, especially since the mobile scenery allows for this. Considering that the opera is in English and that all the creators, except for you, live in America, is it possible that a performance could take place in New York, Chicago, etc.—on the American circuit?

Of course. Long before the premiere, we had a “workshop” of the first act at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Right now I’m involved in negotiations about a similar viewing option for the second act in the university’s vocal faculty. It won’t be the whole show, but even so I hope to have another such “workshop,” maybe next year.

Without the painting Black Square, without the museum setting?

Right now, yes, without, but if we manage to work things out with some museums, I’ll be very happy. It’s possible that we could use Kandinsky, for example, instead of Malevich… If we receive an offer to do a similar performance in the US, then why not?

Especially since the Art Institute of Chicago has a large Kandinsky collection. So why not?

Ilya Demutsky (Photo by Daniil Rabovskii; thereklama.com)

“The music is very emotional”

From Black Square—a completed project—onto the one coming up so soon. Why Tolstoy, and why Anna Karenina?

It wasn’t my idea. Joffrey Ballet asked choreographer Yuri Possokhov to create a ballet based on Anna Karenina. As it usually happens, they gave the choreographer carte blanche as to the choice of music. It could have been either preexisting music or music specially written for the ballet. After our joint ballets, Possokhov proposed that Joffrey use the Russian composer Ilya Demutsky. What we managed to come up with—we’ll see on February 13.

There have been more than a few ballets based on Tolstoy’s novel. Shchedrin’s ballet for Plisetskaya. Eifman’s ballet to Tchaikovsky’s music. Christian Spuck’s ballet to the music of Rachmaninoff, Lutosławski, Tsintsadze, and Bardanashvili. Neumeier’s ballet to Tchaikovsky, Schnittke, and Kate Stevens. Angelica Cholina’s ballet at the Theatre Vakhtangov in Moscow, with music by Schnittke. Yuliy Kim and Roman Ignatiev’s musical at the Moscow Operetta Theatre. Valery Gavrilin’s opera… What is it about this story of Tolstoy’s that attracts such different composers, choreographers, and directors?

There are a lot of shows, but only one with original music—the ballet by Rodion Shchedrin. All the rest are generally Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, some kind of precomposed material. I don’t like when music that was written for other purposes and with other themes in it is reused in what is, in my opinion, a completely unsuited context. But that’s another conversation… Why Anna Karenina? First, the novel is very suited to the stage. Yes, wildly complex for the stage, multilayered, and interesting for that reason. Every choreographer or opera director can find something of their own in this material. You can focus on Anna’s story or Levin’s story, you can make Anna a secondary character and talk about the fate of the Russian peasantry… Every staging is irreplicable; each one has something of its own. That’s the attraction of Tolstoy’s novel. It still feels “alive” to this day, and it’s inexhaustible in terms of interpretations.

What is new in your version? What do you concentrate on?

In our version, Levin plays a large role. We devote more attention to him than do other ballets. But of course, we wouldn’t be able to pull it off without Anna’s story. Without the train or, so to speak, an interpretation of the train. We won’t have a straightforward interpretation. Maybe it will be expressed somewhat differently… The ballet’s still being developed. Right now it’s hard for me to talk about the concept behind it, even though one is present, absolutely, in the libretto. There’s morphine, and Anna’s delirium, her condition… We devote a lot of attention to sleep, the Sandman, and dreams. We never know what is reality and what isn’t—what is happening onstage. It’s a kind of story through a prism of intoxication, from narcotics or from love. And it will have a mystical element. That’s where everything is mixed together…

I realize that just talking about the music is useless. You need to listen to it. But all the same… what will the music of Anna Karenina be like?

I used practically all the standard instruments of a symphony orchestra. As is usual for me, the music is very emotional. There are melodies, maybe memorable ones. Very rich harmonic language. It’s not minimalism, not avant-garde, but traditional and, I guess, cinematic music. The love theme works its way in throughout the whole work, through the leitmotifs. It varies depending on the chemistry between the characters, Anna and Vronsky’s conditions. There are themes for high society and the ball, and they also sound different based on what is happening on the stage.

When you’re composing a ballet, do you think about the dancers or do you write general-purpose music and leave the questions of how to dance to it for the choreographer?

Sometimes I think about how it will be performed, about the skill level of the orchestra. I can’t allow myself to write a score that would take months or half a year to learn. Everything is connected to the budget and to how many rehearsals there will be. Therefore it has to be music that’s easy enough to sight-read but that still has a big effect. Plus, it has to work for the given ballet company. If it’s a company that presents itself as traditional, classical ballet, then it’s probably not entirely appropriate to try to break with that. Some composer comes along and decides to make a new identity for them. No. But even so, you can try, within the traditional musical canvas, to put in a sudden touch of something unusual, something that maybe has never been done in the theatre before. This is an interesting challenge both for me and for the choreographer.

Have you seen any performances by the Joffrey Ballet? Could you talk a bit about their capabilities in terms of technique?

The company is in great shape. I watched some recordings of their shows on the Internet. I saw the new Nutcracker by Christopher Wheeldon live. I know Victoria Jaiani; in fact, I’m friends with her. She came to Moscow and danced a part in one of my ballets. She’s an incredible dancer. I’m happy that she’s going to be performing the main role.

I also really like her husband, the dancer Temur Suluashvili. A wonderful couple from Georgia! And your fellow countrywoman Valeria Chaykina also dances with the Joffrey Ballet.

I also met her last time I was in town… The company is stunning. I sat in on their rehearsals a couple of months ago. The material was still unpolished, but I could still see that the ensemble takes a lot of pleasure in being receptive to the music and the choreography and performs it just brilliantly. I think it will be interesting work! I’m excited…

Will you be present at the rehearsals in Chicago?

I’ll join them about a week before the opening night. I can’t say that I’ll interfere very much. On no account do I ever interfere with the choreography. It should already be finished by that time. I’ll come to the rehearsals with the orchestra in order to make sure that there are no issues. Creating a new score always involves a lot of responsibility, but to be honest, my presence isn’t really necessary. My input is already written down in the sheet music. A competent conductor won’t have any problem reading the music. Like other people, I’ll come to the premiere—to enjoy it, not to work!

If Anna Karenina gets picked up by the Bolshoi, will you make any adjustments to it, or will you give it to them exactly in the form in which it will be performed in Chicago?

If the Bolshoi will perform it in the form in which we have it now, there’s no sense in changing anything. I would understand if it were a smaller company. In that case, we would need to make some adjustments. I only see the need for adjustments in cases of new staging, new choreography, new stage design.

Is it easy for you to part with a piece of music? If Yuri or one of the soloists says that one or another fragment is hard to dance to, will you compromise with them?

I always compromise with them, we find a compromise. I don’t think I’ve ever run into a situation where we just cut material. To the contrary, there have been times when we expanded it. Once Yuri told me that his idea wasn’t being expressed fully enough and asked me to add something in. In A Hero Of Our Time I cut three minutes of music on my own initiative. I realized that the music was in a slump, there was no development there. I could see that those three minutes were no longer needed. Everyone agreed… We have a friendly team. We listen to each other. In this respect working with Yuri is very comfortable.

What a thrill for a choreographer—working with a composer!

Yes, and for a composer, working with a choreographer.

The Joffrey Ballet is well acquainted with Possokhov. Last season his choreography was used in The Miraculous Mandarin, to music by Bartok. It was a big success. But how did your collaboration with Yuri begin?

Originally I got acquainted with Kirill Serebrennikov. He was the one who invited me to work on A Hero of Our Time. He showed Yuri and the Bolshoi Theatre my work. It was only after that that I met Yuri. We immediately found a common language. I came to Moscow to meet him, and on that same evening, we started working on Hero, discussing ideas.

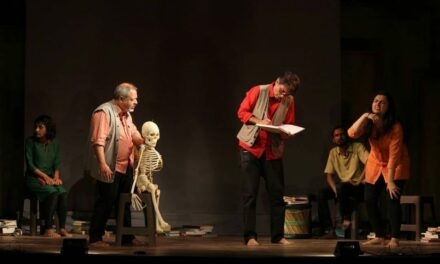

Scene from A Hero Of Our Time at the Bolshoi in St. Petersburg (Photo by Damir Iusupov; thereklama.com)

“There’s just one criterion—the music should give you chills”

Ilya, I’d like to talk about your experience in the United States. Many musicians consider the Saint Petersburg Conservatory to be the most prestigious academy in the world. Mariss Jansons said that according to his ranking it’s in first place, and the Vienna Conservatory in second. Why did the Petersburg Conservatory seem insufficient to you, and what did you gain from attending the conservatory in San Francisco?

It’s difficult for me to talk about categories of “prestigious” and “not prestigious.” Of course, the Saint Petersburg Conservatory has a very strong primary school. Solfeggio, history of music, polyphony, harmony, vocals, piano, etc.—a fantastic and very important part of one’s training. I was a little short on practical work. I mean access to a live orchestra. It’s no secret that at the Petersburg Conservatory composers work with a live orchestra for the first time in their final year of study, and they’re lucky if they get twenty minutes with them. I consider this a disaster. Composers, unfortunately, frequently graduate from the Petersburg Conservatory not knowing how to write for an orchestra. They don’t know the elemental things, like how the pedals on a harp work… At San Francisco, I studied those disciplines that aren’t available at the Petersburg Conservatory. For example, orchestration. I don’t mean Rimsky-Korsakov’s monograph on the subject, which is almost one hundred and fifty years old, but the fantastic textbook by Samuel Alder — a huge volume with interactive components [Demutsky is talking about Alder’s book The Study of Orchestration—S.E.]. It’s written in fairly simple language and updated with new musical and technical developments every two years… A substantial part of the San Francisco Conservatory was practical training. I came and talked to musicians: flutists, violinists… We had opportunities for mutually beneficial collaboration: I would offer to write for a musician, and he would tell me how his instrument worked… At San Francisco, I was able to obtain any sheet music I needed within a week. All you needed to do was put in an order at the library. At the Petersburg Conservatory I ran into times where they simply wouldn’t give certain music to me just because “Sorry, it’s old, rare, expensive.” That being said, I’ll repeat: we have an incredible school. I’m deeply grateful to my outstanding instructor, professor Tatiana Ivanovna Khitrova. Every place has its pluses, but there are also plenty of minuses.

They say John Adams taught you at San Francisco…

Adams wasn’t my instructor. One time he taught at our conservatory, and he visits there fairly often. I took part in his master class. He commented on my choral piece, written in Russian, even though he said he didn’t understand a word of it. While I was studying there, Adams had an anniversary celebration. There was a week dedicated to his music and discussions with him. But my instructor was David Conte.

By the way, on the topic of Adams—what is your opinion on the work of minimalist composers (Adams, John Cage, Philip Glass)?

Because I’m a deeply emotional person, minimalism sounds somewhat flat to my nature. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t like minimalist music. I don’t agree, for instance, that all of Adams’s music is minimalist. It’s not true. Harmonielehre, for instance, is a stunning opus. Deeply emotional. There are traces of minimalism in it, techniques, but we can find those same techniques in Beethoven as well. Everything depends on the specific work. Taken in general, minimalist music is not close to my heart. For me, the emotional components of music are important. We should break down, soar up, sigh, marvel, and not be on one level the whole time. An hour of music with the same emotion—that’s not so interesting to me. When that’s the case, the music becomes background noise that doesn’t make you think about anything—it just relaxes you and has a meditative quality. I don’t like when music has a meditative quality. I can get the same result listening to that as to grasshoppers chirping.

Naiman’s score for Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is absolutely meditative music throughout the entire film. Do you not like that score?

In cinema, it works wonderfully. Both Nyman’s and the aforementioned Glass’s. But I can’t, unfortunately, listen to that kind of music through headphones for very long.

Do you have your own sort of step-by-step process in music depending on the genre?

Without question, I think about which genre I’m working in. With opera, above all, I begin with the plot, with what should be included in the music apart from the words, which meanings, which layers. Opera means a lot of resources and a large orchestra. With film, these days, they often ask you to limit the size of the orchestra based on the budget, to make due with minimal resources. I often turn down film work for that reason. And back to background music… I’m not interested in working in that genre. The very idea of background music in cinema is unpleasant.

The whole thing probably depends on the director. It seems to me that your music for The Student by Serebrennikov is absolutely not “background”…

Kirill gave me carte blanche. He told me, “Don’t try to ‘write Mickey Mouse’; underscore whatever is happening. The music should run its own course.” In cinema, everything depends on the words, on what needs to be shown in the scene. We can see one expression on the character’s face, whereas he’s actually thinking of something completely different, and I, as the composer, need to emphasize this. In ballet there are no words, so the music is tremendously important. Apart from the choreography and the body language, the music tells you what’s going on: whether it’s lighthearted love or disappointment, tragedy or a dream, or happiness… Strangely enough, it’s the music that’s fundamental, although a competent choreographer can also depict an emotion in total silence. My challenge is to put maximum emphasis on the emotion, so that, so to speak, there are no doubts left or specifically so that they do arise.

Who are your favorite composers?

Of course, Bach—the most emotional composer. All things considered, it’s baroque music with classical elements. I simply worship his Mass in C Minor. As someone with a choral background, I feel this mass to be absolutely sacred. Bach is unique… Mahler, Richard Strauss, Shostakovich, Prokofiev. Stravinsky, of course. Not all of his music, maybe, but his Russian period, neoclassical. The Bells and All-Night Vigil by Rachmaninoff—masterpieces of choral music… Penderecki. I’m interested by what he’s doing. If at first, he was avant-garde and exploratory, now he’s in a neoromantic period. He often visits Saint Petersburg, appears at the Mariinsky… I like what Shchedrin is doing. I never miss one of his premieres. A complex composer and very interesting… There’s just one criterion—the music should give you chills.

Scene from Nureev at the Bolshoi in St. Petersburg (Photo by Pavel Rychkov; thereklama.com)

“Music as performance art isn’t interesting to me”

Which of your works is the most important to you?

Whichever one I’m working on at the moment. Once I’ve finished writing a work, I let it go. I go to see Nureyev and A Hero of Our Time, watch The Student, listen to my music, but I’m already so distanced from it that I can experience it as a listener or an audience member. I never have the desire to rewrite music. That’s it, the work is done. It’s the music I was feeling at the moment when I wrote it. Of course, were I to write it now I would do so completely differently. You can rewrite and edit infinitely. There’s simply not enough time in a life for that. It’s already not my music anymore. Some other Demutsky wrote that. Yes, I can hear some shortcomings from the vantage point of the present, but there’s a sort of charm to that… Nothing thrills or inspires a composer as much as completing something. Undoubtedly, I’ll fall in love with Anna Karenina all over again when I hear it live in February, but for now, I’m completely focused on other projects.

If they ask me to name one work by Demutsky in Chicago, which one would you recommend? What’s on your “musical business card”?

Above all, the ballets A Hero Of Our Time and Nureyev. My name became known thanks to ballets.

I first heard of you after your symphonic poem The Closing Statement of the Accused for mezzo-soprano with an orchestra, based on fragments of Pussy Riot member Maria Alyokhina’s closing statement to the court. What was the fate of that work?

Understandably, it’s not possible to perform it in Russia. Thanks to this work there’s still a bit of a stigma around me. Even now I still have some difficulties, including in my native and beloved Saint Petersburg. For example, the opera New Jerusalem, which as of right now has never been performed. We had planned for it to open in spring 2014, and I held two rehearsals with the chamber orchestra. But then we were forbidden to perform it, and the premiere went up in smoke. When I tried to resume work on the opera a few months later, they came for me… At that time I was already working on Hero, everything got so busy, and now there’s not enough time for it…

What do you think—will the premiere of New Jerusalem ever happen?

I hope so. New Jerusalem and The Closing Statement Of The Accused aren’t ephemeral works. They’re relevant now, even more so than they were then, considering everything that’s happening with the Serebrennikov trial. The works are possible to perform, even though they’re technically very difficult. Huge orchestra composition, a strong mezzo-soprano… You need to dedicate yourself to it, and unfortunately, I don’t have the time right now.

I’ve read quite a few reviews about your previous operas and ballets. Many wrote that they could feel Tchaikovsky’s and Minkus’s influence in the music to Nureyev. About Black Square, they said the music was influenced by twentieth-century composers—Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Stravinsky. At the end of the day, to what extent can the music of today be free from the influence of its precursors?

It can’t be if we’re talking about tonal music. How can you write melodies based on harmonic progressions and not have them evoke any sort of associative line? If you’re someone who’s listened to enough music, you will undoubtedly be reminded of previous composers. In Nureyev, I simply used the music of Tchaikovsky and Minkus. There were direct “quotations” from their ballets in that score, because that was the nature of my artistic task. After all, I was writing a ballet about Nureyev, and we couldn’t avoid that part of the story. And in Black Square—yes, it’s true that there are allusions and references in there. It’s a perfectly normal process for composers to invoke the huge reservoir of past works that their own music stems from. It’s even the same with avant-garde composers, who think for some reason that they’re doing something new. They’re no different; Ligeti, Tristan Murail, and others show up in that associative series. This kind of discussion is unproductive. I never respond to it. If someone is compelled to hum the music they just heard as they’re leaving the theatre, then that’s wonderful. I consider that a compliment. Music should stick in your head, not be something you only think about once or for one day. I’m against one-time, performative music. Music as performance art doesn’t interest me. Music is interesting if I want to listen to it more than once.

Has something revolutionary emerged from twenty-first-century music, or have all musical discoveries—tonal or atonal—already been made in the past?

I don’t think anything new has emerged. Searches are occurring. The main thing right now is the convergence of genres, a combination of music with theatrical art, a “new” approach to words, but “new” in quotation marks because in principle it’s already been done. Music hasn’t come up with anything new not just in the past twenty, but in the past forty or fifty years. Minimalism was the last new trend. Since that nothing new has appeared in classical music. The introduction of new tone qualities doesn’t constitute new music. With the invention of new technologies, it became a matter of course, but that doesn’t mean that music started speaking a new language.

What you said about the convergence of genres, Wagner called “Gesamtkunstwerk.” He did this in Bayreuth a hundred and fifty years ago.

Of course. The involvement of the orchestra musicians in the action is also nothing new. During Haydn’s Farewell Symphony the performers exited the stage in turns, and that was almost two hundred and fifty years ago. At the time that was innovative, but not today. To me, nothing new has happened in music yet this century. I don’t think, by the way, that that’s a bad thing. A composer can work within the genres that already exist. If it’s convincing, then it’s wonderful.

“Being a composer—it isn’t teamwork”

Recently many of your colleagues have been working with the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre. Boris Yukhananov has solicited new operas from them. One of those operas, Drillians, was successfully shown in the United States in the Stage Russia HD series. You’re not one of those composers involved with the theatre. Were you not invited, or did you yourself not want to participate?

I’ve stepped back somewhat from associating with colleagues. First of all, those people are all from a different generation. Older than I am by at least ten years. They’re interested in things that don’t interest me at all. I deeply respect them for what they’re doing, for seeking something new and discussing this. But I feel comfortable in my own area, the one in which I’m working.

You consider yourself a lone wolf?

In my opinion, being a composer—it isn’t teamwork. A composer has no reason to befriend and mingle with his colleagues. It’s more interesting to associate with directors, choreographers, musicians and performers… But with composers… Philosophical searches and conversations aren’t of interest to me… I can read about all of that in books. I’m comfortable as, you’re right, a lone wolf.

Why, in your opinion, are works by modern Russian composers not well known in the West? Even Schnittke and Gubaidulina are completely unheard of. Their music is performed in Europe, but in Chicago, for example, almost never. The last time I heard Schnittke in performance was by Gidon Kremer and his Kremerata Baltica ensemble. That’s it. Not to mention you and your contemporaries…

Russian composers aren’t well known in the West. At the San Francisco Conservatory, I asked: “Which living Russian composers do you know?” Aside from Gubaidulina, who’s already a living classic, they couldn’t recall even Shchedrin without prompting. People don’t even know their names. But Russia itself is to blame for this—it never exports classical music. Are there many Russian orchestras that perform music by living composers when they go on tour outside the country? The Mariinsky partners with Shchedrin, something by Jurowski is performed in the West, something by—Currentzis… This is a problem for orchestras’ conductors and directors. For an American orchestra to perform a Russian composer, it has to first find out about his or her existence. This is a question of PR, advertising, and so on. The Joffrey Ballet found out about me because Possokhov invited me to come work with them. Now my music is heard; maybe someone will like it, and it will start to be performed. That’s how the market works. For better or for worse.

But that being said, if you ask someone on the street, they’ll always name Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Prokofiev. That is, all in all, Russian music is being performed in huge quantities. But it’s far, far away from us…

The classical masterpieces are performed, and that’s not all. The Nutcracker is performed more often in America than it is in Russia. This is also a great thing. But that being said, it wasn’t long ago that [Tchaikovsky’s] Iolanta was performed in Chicago for the first time!… In Germany and in Europe generally, the situation is better, because there a different aesthetic predominates to this day. In America, in my opinion, the development of music is going a completely separate way. For example, Mason Bates, who’s beloved and frequently performed in Chicago, is absolutely not an avant-gardist. He mixes the orchestra with technology, but that’s something any person off the street can understand. He’s not afraid of the audience’s understanding, he can even play around with it. It’s good. It’s worse if someone comes, listens to a classical concert, and decides that they’ll never go to another one again… In Russia, music by contemporary composers is practically never performed. Recently a wonderful festival called Other Space took place (Vladimir Jurowski runs it)—there was a series of premieres of new composers. That’s the kind of thing we need to be doing. And where else is new music being performed? The Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra has performed music by maybe one living composer in the past five years? I haven’t heard it. This is a question of arts patronage, commissioning new works, the involvement of an institution and its artistic directors… I’m happy that over the past four or five years, theatres—the Electrotheatre, the Bolshoi, the “Stasik” [Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Academic Music Theatre], the Permskii…—have begun commissioning new music. In this respect musical theatre is, in my opinion, moving in the right direction. There is interest and there are audiences. Everyone loves the classics, but how many times can you watch The Nutcracker? Let’s do something new, and time will tell whether it lasts or not.

In October the general director of the Bolshoi, Vladimir Urin, announced that the theatre would be commissioning a new opera for the first time in fifteen years, since Desyatnikov’s Children of Rosenthal. They brought you in. After two ballets, you’re now writing an opera based on Aleksandr Grin’s novel The Shining World. That seems like a fascinating topic to me! Flying Drude as a symbol of freedom and the persecution of him by those in power—it’s precisely Kirill Serebrennikov! Are you afraid that people will see allusions to the present day in your opera, or that some people will be offended by it?

I believe that musical works should speak to the present day. Grin’s novel is almost a hundred years old, but it’s still relevant today—a sign of genius in a work of art. Grin speaks to the present day and to eternity. To me, that’s the goal of the opera—not to be about the evils of today such that it will hold no interest by tomorrow, but to speak to what is troubling both now and always, at the same time. I’m grateful to my mother, who brought this book to my attention. When I read it, I immediately realized that the novel was absolutely stageable and could be beautifully portrayed in an opera. I hope that inspiration doesn’t betray me. Right now I’m putting the finishing touches on the libretto to make it more convenient in terms of stage design.

Who will be the director?

It’s early for that discussion. I’m speaking with a couple of directors. We need to be in sync with the time limits that exist at the Bolshoi. The opera is set to premiere in the 2020–21 season.

In October the media reported that “Serebrennikov and Demutsky are working on joint projects.” Does this mean you’re optimistic about the Seventh Studio case?

Yes, I’m optimistic. We have a lot of ideas that we will definitely make something out of. We’re in contact rarely, through lawyers, but we are in contact, and in court, a couple of words can spread. I’m sure we’ll work together in the future more than once, in a variety of genres: from musical theatre to film.

Many people are saying that if the trial goes the way that it should and that we all want it to, and Kirill walks free, he will emigrate from Russia. As [actress] Chulpan Khamatova said in an interview with Nikolai Sodovnikov on his YouTube program: “That will be better for him.” What do you think, will Kirill leave?

I think if he doesn’t leave, then at any rate, most (maybe all) of his projects will be in the West. I also think that if Russia doesn’t accept its heroes, why should he let it destroy his life? He’s already suffered enough.

What will happen to the Gogol Center?

Solutions will be found. It’s hard for me to say, because I’m a free agent and, luckily, not connected to any sort of institution… He will probably need to let the Gogol go, like a child. Like I do with my creations, and just watch from the side. The main thing is that Kirill and all the parties in the Seventh Studio case be freed, that Kirill be fulfilled as an artist and make us all happy… Here not everything gives way to logic. The one thing is—you have to believe. I always hope for the best.

Let’s hope for the best!.. Ilya, this isn’t your first time in Chicago. What do you think of the city?

Unfortunately, I always come to Chicago during the cold months. But all the same, I really like the city, its cultural diversity. I like the river—similar to the canals of Saint Petersburg… Chicago is one of my favorite American cities. Sadly, I’ve only visited it for short periods of time. But even over the course of a few days, I managed to fall in love with the stunning art gallery, the parks, and—above all—the people. They’re unique, and that makes them pleasant to talk to. Chicago’s energy is very close to my heart. It’s not the crazy energy of Moscow and New York—it’s more measured, but still high-tech. Next time I hope to explore Chicago even more.

You’ve come during a cold month again. Don’t expect anything good from the weather!

I’m coming from Petersburg, so I’ll be ready.

See you in Chicago!

This interview originally appeared in the Russian language in Reklama magazine. It is printed in translation with permission of the author.

Translated by Rose Fitzpatrick

Sergey Elkin

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sergey Elkin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.