Grace is one of two daughters in an educated family living in Canada. She loves her parents and trusts them. She goes to daycare. She has friends, one of whom is her best friend. Grace and her best friend play together at Grace’s home sometimes, and sometimes they play at Grace’s friend’s house. Their parents know each other, too. They visit each other and get along well. Then, Grace’s friend moves to the US from Canada. One day, Grace and her family go to visit these friends in their new American home.

Some friends! In fact, Grace has experienced physical and mental sexual abuse by her best friend’s father for several years, even while she had been going to daycare. And she was raped by her best friend’s father during her holiday in the US, when she was just seven years old. Seven!

Grace was raped when she was only seven years old. The man who had assaulted her was a family friend; he was not a stranger as is typically thought. According to data mentioned in the documentary play, reviewed in this article, “in 79% of cases of child sexual abuse, the child knows the offender.”

Because of her relationship with her family, Grace thinks that the adults in her life are people who must know the truth and who must be trustworthy as she tries to make sense of what she is exposed to. She is confused and blames herself. That is why she does not say even a word to anyone about what has happened to her for many years.

Grace is a child of a family who is thought to be “lucky.” She is a member of a family who are educated and white. Her family members have no financial problems, so they can easily access many opportunities. Whereas she previously had been an extrovert, a warm and cheerful child, her behavior and mood have changed since the incident. Her parents had noticed the changes; thus, they have arranged for her to see a psychologist. However, she said nothing even to her psychologist until she was fifteen years old. Subsequently, she has disclosed her story first to a couple of her friends, then to her psychologist, and after her sixteenth birthday to her parents. Afterward, the family enters a process that includes facing the other family, going to the police, filing a lawsuit in the US, explaining everything over and over again during the legal struggle, and trying to convince people that they are telling the truth. Moreover, they must prove their accusations. It takes a year for the legal piece, which for Grace seemed more like three years. Dozens of phone calls and other correspondence, meaningless questions, brutal reports, and suspicious glances. What if she is lying? What if she just imagined everything? What if she made up her childhood with the same ability to weave fiction that she uses in her poems and stories? What about the proof? In the courts, justice(!) means the offender must confess his/her guilt, or the claimant must prove his/her claim. That is how the legal system works. Besides all this, not only Grace but also her whole family are forced to talk about the events over and over again. For one year, not only Grace but her entire family are forced to go through this pain over and over again.

The result? Despite persuading the court verbally that she was telling the truth, the case is lost because she could not prove on paper what she had been through. In other words, the case ended up with just a “legal” result, not a “fair” one.

Grace is in her early twenties now. Her older sister, “Sarah,” offered to share her story. Then, with the help of Grace, her sister turned the story into a theatre script. The play was staged by Andrea Donaldson with a production at Nightwood Theatre, a feminist theatre company in Toronto, founded by a group of women in 1979 and that aims to be a platform where women can make their voices heard.

The playwright, who goes by the name Jane Doe, is the real-life older sister of “Grace,” but neither Jane nor Sarah is her real name. All names have been changed to protect the family’s privacy. No name is given to the rapist. Instead, in place of his name during the play, a disturbing sound effect is used. This use of anonymity is vital to the narrative’s universality because the play’s aim is not to tell people Grace’s anguished story. The objective is to emphasize the functioning of a justice system that punished the victim instead of the guilty.

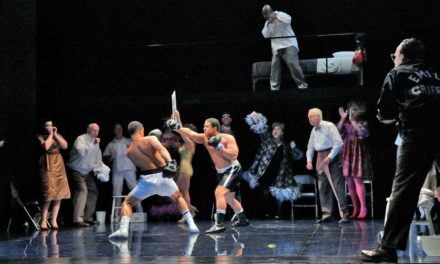

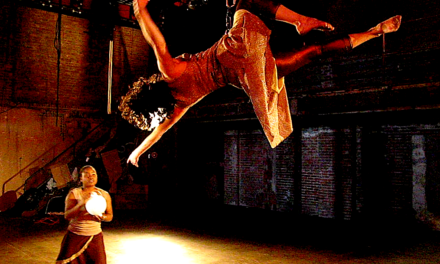

Grace. Directed by Andrea Donaldson, Nightwood Theatre, Toronto. From left to right: Rose Napoli, Michaela Washburn, Brenda Robins, and Conrad Coates. Photo credit: Dahlia Katz.

The script is a documentary narrative divided into chapters. What gives it the feature of a documentary is not only the fact that the subject matter is based on real events but also that statistics and quotations are used.

The set consists of a few standing microphones, chairs, and a small cardboard box illuminated by local light standing in the middle of the stage. When the actors enter the scene, the cardboard box, the presence of which suggests that the audience will see unpleasant things, just as with Pandora’s box, is moved to the edge of the stage. It is held there until the section where it is used.

Four people in casual clothing, Grace (Michaela Washburn), her sister Sarah (Rose Napoli), her mother Diane (Branda Robins) and her father Steven (Conrad Cotes), take their places on stage. The play opens with a short monologue by Grace. Following this monologue, which warns the audience about what they will encounter throughout the performance, Sarah introduces herself and the other actors. It is underlined that what will be seen is a theatre play and that the audience will follow the actors, who will tell Grace’s story. In other words, the audience is reminded that they will not see the real family. Thus, it is intended that the audience not identify with the reality to be described. The physical features of the actors are another choice that supports this approach. The actress Michaela Washburn’s physical appearance does not match Grace’s physical features as described in the script. Also, there are no physical similarities between the two sisters. With this contrast, the performance seeks to distance or to alienate the audience from the characters and action.

During the performance, the actors’ words and the characters’ words are separated through the microphones. In other words, the actors are talking into the microphones as they act out the dialogue between the characters. Thus, the separation between the time of the performance and the time of the story is facilitated.

Through projection design and lighting design, Grace’s dreams and poems are reflected on the back wall, and these add a visual dimension to the performance. This visual dimension also helps remind the audience that Grace is not just a victim. She is a child who has dreams, poems, hopes and wishes, and who loves cats. The audience also sees section headings on the wall, which inform them in advance of each chapter.

The narrative unfolds chronologically. Grace’s childhood, feelings, psychology, relationship with her sister and her parents, what happened in the judicial process for everyone’s perspective, and then Grace’s present and her plans for the future are told over the course of 90 minutes. While one of the actors is talking, others are just waiting, or they are doing small movements associated with the narration. These movements, in which words or images are performed through the body, reinforce the theatricality of the narrative. The forms of acting are quite plain. Grace’s expression and stance evolve throughout the performance, but this change is very millimetric and secretly processed. Whereas at the beginning Grace avoids speaking directly to the audience, she is transformed into someone who is able to liberate her soul at the end. This change can be seen in Grace’s eyes, owing to Washburn’s pure performance. While Sarah is angry and sad at times throughout the performance, Grace recovers as she recounts. Details linked with the assault are not given at any moment during the piece. Moreover, it repeatedly emphasizes that “this piece is not about the assault. It’s about everything that came after.”

Grace wrote about what happened for the police in her first statement. While she explains her own story, she speaks as if she is telling someone else’s story. The statement is in a yellow envelope. And the envelope is imprisoned in the box that we see at the beginning of the performance. It will never be opened.

Although they repeatedly emphasize that “this is a play and we are just playing it,” the actors slide into the emotional feeling of what they are talking about from time to time. At that moment, through the other actors’ touch, they regain consciousness and remember that they are just actors. This nuance is also a warning to the audience to detach themselves from their feelings. It is an impressive choice in terms of reinforcing the healing power created by a touch from the heart. The harmony and energy between the actors and the presented family members reinforce the audience’s awareness that difficulties can only be overcome together.

Grace is trying to defend her rights with the support, albeit late, of her family. She chooses to be a “survivor,” not a “victim.” However, the length of the process and the uncertainty of the outcome are exhausting not only for the victims but also for those who support them. This play proposes that in the process, people experience a “second rape” during the struggle. At the same time, the Nightwood Theater organizes seminars to create a critical thinking environment and to raise awareness. They share book lists, articles, and even critical questions on their website. In other words, they are trying to discuss and keep the issue on the agenda with all the opportunities they have.

According to statistics that are given in the play, “among adult Canadians, 53% of women and 31% of men have been victims of one or more unwanted sexual acts. Approximately 4 in 5, that’s 80%, of those incidents happened during childhood or adolescence.” On the other hand, it is known that the vast majority of people prefer to hide what they have been exposed to because it is so difficult to remember and to explain a situation that is already hard to live with. It can be assumed that it is not “real” if it is not spoken of; however, when it is uttered, it is not easy to deal with others’ reactions of horror, curiosity or pity. Some victims think that it was their own fault. Also, many victims fear that great trouble will arise if they tell someone. Because of that, they often keep their silence for years. They might remember every single detail five times a day, but their silence lasts. And, it will continue as long as everyone else says nothing.

Yes, today is a beautiful day to say something.

—Toronto, March 2019

Grace. Directed by Andrea Donaldson, Nightwood Theatre, Toronto. Rose Napoli, Brenda Robins, Conrad Coates, and Michaela Washburn. Photo credit: Dahlia Katz.

Grace, A Nightwood Theatre production in association with Crow’s Theatre, ran January 8 through January 26, 2019, at Streetcar Crowsnest (345 Carlaw Avenue, Toronto, Ontario).

CAST

Conrad Coates

Rose Napoli

Brenda Robins

Michaela Washburn

CREATIVE TEAM

Playwright – Jane Doe

Director – Andrea Donaldson

Set and Costume Design – Joanna Yu

Lighting Design – Michelle Ramsay

Projection Design – Laura Warren

Sound Design & Composer – Deanna H. Choi

Stage Manager & Associate Lighting Design – Christina Cicko

Assistant Sound Design – Cosette Pin

Production Manager – Pip Bradford

Assistant Director – Sadie Epstein-Fine

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Berna Ataoğlu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.